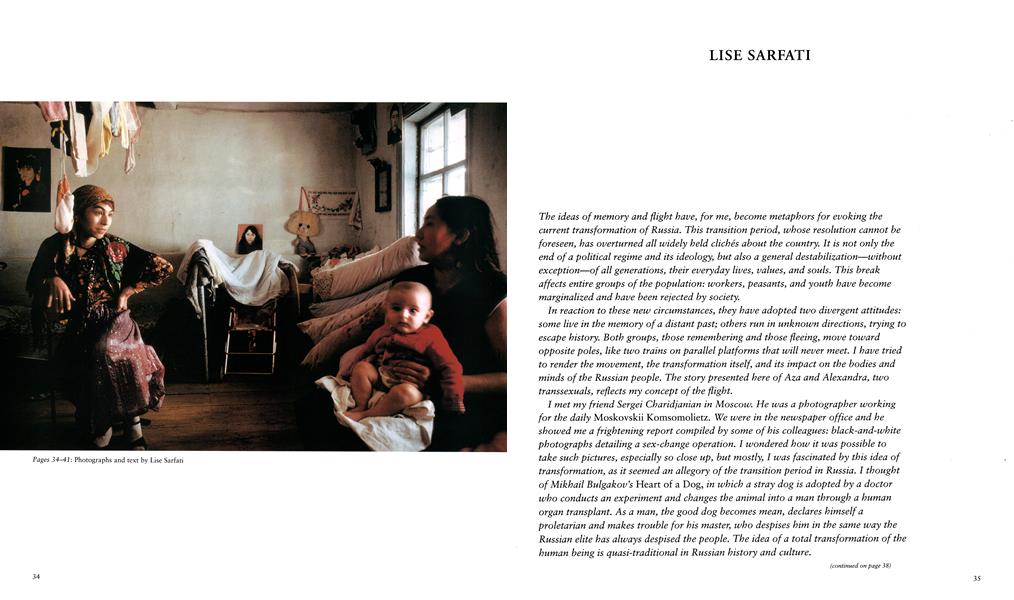

LISE SARFATI

Lise Sarfati

The ideas of memory and flight have, for me, become metaphors for evoking the current transformation of Russia. This transition period, whose resolution cannot be foreseen, has overturned all widely held clichés about the country. It is not only the end of a political regime and its ideology, but also a general destabilization—without exception—of all generations, their everyday lives, values, and souls. This break affects entire groups of the population: workers, peasants, and youth have become marginalized and have been rejected by society.

In reaction to these new circumstances, they have adopted two divergent attitudes: some live in the memory of a distant past; others run in unknown directions, trying to escape history. Both groups, those remembering and those fleeing, move toward opposite poles, like two trains on parallel platforms that will never meet. I have tried to render the movement, the transformation itself, and its impact on the bodies and minds of the Russian people. The story presented here of Aza and Alexandra, two transsexuals, reflects my concept of the flight.

I met my friend Sergei Charidjanian in Moscow. He was a photographer working for the daily Moskovskii Komsomolietz. We were in the newspaper office and he showed me a frightening report compiled by some of his colleagues: black-and-white photographs detailing a sex-change operation. I wondered how it was possible to take such pictures, especially so close up, but mostly, I was fascinated by this idea of transformation, as it seemed an allegory of the transition period in Russia. I thought of Mikhail Bulgakov’s Heart of a Dog, in which a stray dog is adopted by a doctor who conducts an experiment and changes the animal into a man through a human organ transplant. As a man, the good dog becomes mean, declares himself a proletarian and makes trouble for his master, who despises him in the same way the Russian elite has always despised the people. The idea of a total transformation of the human being is quasi-traditional in Russian history and culture.

(continued on page 38)

(continued from page 35)

I went to the Basseinova Hospital in Moscow. After the traditional interview with the physician in charge of sex-change operations, I was allowed to go into hospital rooms to talk with the patients. As I opened the doors of those rooms, I found myself in a nightmarish labyrinth. Their occupants were tired and often disheveled; most came from the country.

I was filled with admiration for Aza and Alexandra. The two friends were from the same remote village in Kazakhstan and had decided to come to Moscow together for their operations. I knew that in Russia’s past, gays were sent to camps and lesbians to psychiatric hospitals. Now, in today’s Russia, Aza and Alexandra would even get new identity papers. But they had a long way to go: they first had to undergo a psychiatric analysis at Rostov-on-Don in order to determine whether they were really transsexuals or else schizophrenics. Then they had to find the money to pay for the operations.

Azamat was seventeen and became Aza. Alexander was twenty-four and became Alexandra. I cannot explain the magic of our relationship or the reason why they accepted me; naturally, the fact that I was a woman mattered a great deal. Whatever the reason, we had a good rapport. I don’t think it had anything to do with photography. They understood that I was not a voyeur. I love to play, and they did too; they were very distrustful, like me, and also very intuitive. They recognized genuine people who did not play games with them, who respected them, and who did not fall prey to anecdotal curiosity. They understood me as a person outside of the norm, impossible to categorize.

Often, I slept in their bed while they went cruising in the hospital corridor. They were very excited by the sex change. They watched themselves in the mirror and smiled. Everything was a discovery. I felt like I had just given birth to two adult babies. They did the conventional or cliché girl things all day long: painting their nails, combing their hair, putting cushions on their stomachs to pretend that they were pregnant. They wanted to compare their genitals to mine, and I must say that in that instance, I was more shy than they were.

As the days passed, they felt stronger and decided to go back to Gelezinka, the small village in Kazakhstan where their parents lived. Aza did not work but read Tarot cards. At least she said she did, but I never saw her perform. Alexandra was a hairdresser. We reached their village after a long trip. In the airport, Aza saw a black man for the first time. With a disgusted air, she asked me if I could go with her to take a closer look at him. She wanted to check to see if he had eyelashes.

At the village, their families were awaiting us. They didn’t believe in the operation. They saw Aza and Alexandra as they had left them—dressed up in women’s clothes. I stayed for a few days, then I left.

I saw Aza and Alexandra in Moscow one year later. They needed surgery again. The original sex-change operation consists of modifying genital organs and creating a vagina. Sometimes there need to be some follow-up procedures.

At the hospital, Alexandra met Andrei, a former woman who had become a man, and they got married. They went to live with his parents in the village where Andrei was born, in the Caucasus. I went to visit them some time later. It was winter and we stayed indoors. They were happy, but in the village, they were called “the transformers. ”

I saw Aza in Moscow one year after her second operation. She had dyed her hair platinum blond, felt sick all the time, and she barked when I wanted to take a photograph of her. I showed my pictures to the great Russian psychiatrist Boukhanovski at Rostov-on-Don, refraining from comment. After he saw Aza in the hospital, he said to me: “She is schizophrenic. She should never have had the operation. ”

From my encounter with Aza and Alexandra, I have put together this story as a photographic series with a single focal point: transformation. I feel that it is this point alone that allows me to share this experience.

Translated from the French by

Chantall Combs