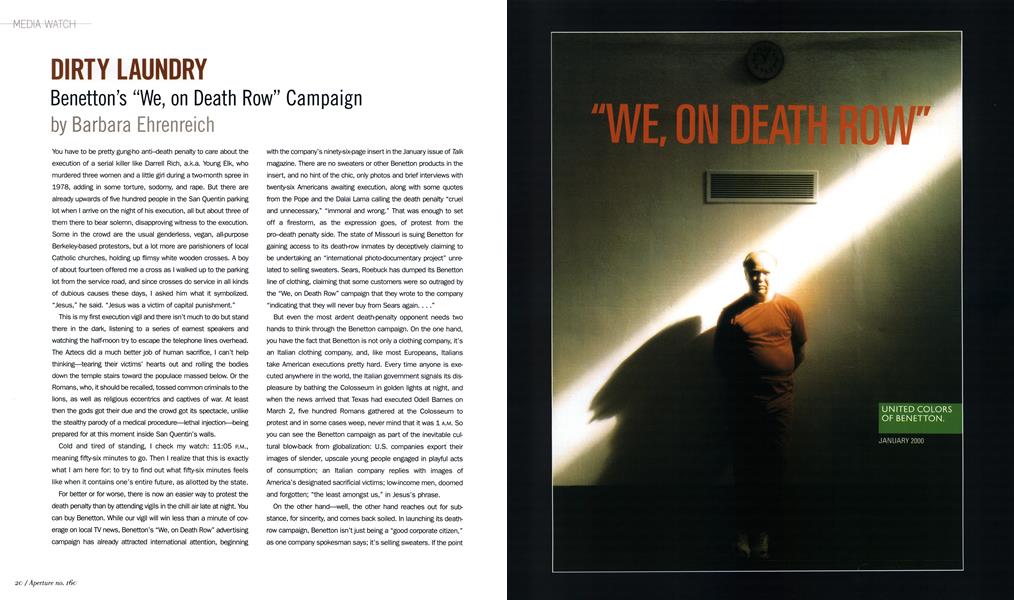

DIRTY LAUNDRY

MEDIA WATCH

Benetton’s “We, on Death Row” Campaign

Barbara Ehrenreich

You have to be pretty gung-ho anti-death penalty to care about the execution of a serial killer like Darrell Rich, a.k.a. Young Elk, who murdered three women and a little girl during a two-month spree in 1978, adding in some torture, sodomy, and rape. But there are already upwards of five hundred people in the San Quentin parking lot when I arrive on the night of his execution, all but about three of them there to bear solemn, disapproving witness to the execution. Some in the crowd are the usual genderless, vegan, all-purpose Berkeley-based protestors, but a lot more are parishioners of local Catholic churches, holding up flimsy white wooden crosses. A boy of about fourteen offered me a cross as I walked up to the parking lot from the service road, and since crosses do service in all kinds of dubious causes these days, I asked him what it symbolized. “Jesus,” he said. “Jesus was a victim of capital punishment.”

This is my first execution vigil and there isn’t much to do but stand there in the dark, listening to a series of earnest speakers and watching the half-moon try to escape the telephone lines overhead. The Aztecs did a much better job of human sacrifice, I can’t help thinking—tearing their victims’ hearts out and rolling the bodies down the temple stairs toward the populace massed below. Or the Romans, who, it should be recalled, tossed common criminals to the lions, as well as religious eccentrics and captives of war. At least then the gods got their due and the crowd got its spectacle, unlike the stealthy parody of a medical procedure—lethal injection—being prepared for at this moment inside San Quentin’s walls.

Cold and tired of standing, I check my watch: 11:05 P.M., meaning fifty-six minutes to go. Then I realize that this is exactly what I am here for: to try to find out what fifty-six minutes feels like when it contains one’s entire future, as allotted by the state.

For better or for worse, there is now an easier way to protest the death penalty than by attending vigils in the chill air late at night. You can buy Benetton. While our vigil will win less than a minute of coverage on local TV news, Benetton’s “We, on Death Row” advertising campaign has already attracted international attention, beginning with the company’s ninety-six-page insert in the January issue of Talk magazine. There are no sweaters or other Benetton products in the insert, and no hint of the chic, only photos and brief interviews with twenty-six Americans awaiting execution, along with some quotes from the Pope and the Dalai Lama calling the death penalty “cruel and unnecessary,” “immoral and wrong.” That was enough to set off a firestorm, as the expression goes, of protest from the pro-death penalty side. The state of Missouri is suing Benetton for gaining access to its death-row inmates by deceptively claiming to be undertaking an “international photo-documentary project” unrelated to selling sweaters. Sears, Roebuck has dumped its Benetton line of clothing, claiming that some customers were so outraged by the “We, on Death Row” campaign that they wrote to the company “indicating that they will never buy from Sears again. . .

But even the most ardent death-penalty opponent needs two hands to think through the Benetton campaign. On the one hand, you have the fact that Benetton is not only a clothing company, it’s an Italian clothing company, and, like most Europeans, Italians take American executions pretty hard. Every time anyone is executed anywhere in the world, the Italian government signals its displeasure by bathing the Colosseum in golden lights at night, and when the news arrived that Texas had executed Odell Barnes on March 2, five hundred Romans gathered at the Colosseum to protest and in some cases weep, never mind that it was 1 A.M. SO you can see the Benetton campaign as part of the inevitable cultural blow-back from globalization: U.S. companies export their images of slender, upscale young people engaged in playful acts of consumption; an Italian company replies with images of America’s designated sacrificial victims; low-income men, doomed and forgotten; “the least amongst us,” in Jesus’s phrase.

On the other hand—well, the other hand reaches out for substance, for sincerity, and comes back soiled. In launching its deathrow campaign, Benetton isn’t just being a “good corporate citizen,” as one company spokesman says; it’s selling sweaters. If the point were simply to contest the death penalty, the words “United Colors of Benetton” would be buried modestly within the Talk magazine insert, for example, instead of being highlighted in bright green on the cover. And surely the faces of the doomed would not be showing up on billboards over the caption “United Killers of Benetton.” For one thing, some of them are probably innocent, condemned simply by their inability to afford competent legal defense. But “United Death-Row Inmates, Some Innocent and Some Not, Of Benetton” probably wouldn’t work on a billboard.

The Benetton campaign is a classic example of what is known in the marketing business as “branding”: attaching to one’s product a sensibility that, it is hoped, consumers will want to acquire for themselves. Nike isn’t just sneakers; it’s youth and triumph and Nietzschean overcoming. Marlboro is rugged manliness; Apple, intellectual nonconformity. And Benetton has, over the years, already positioned itself at the edge of the taboo, which is of course precisely where the much-sought-after quality of “edginess” resides. One of the company’s past campaigns celebrated interracial love; another featured a man dying of AIDS. Forbidden love, a stigmatized disease, and now state-sponsored, ritual killing. You can wear your Benetton summer cropped-neck T to say “I care,” or maybe just “I dare.”

But then—did I say you need only two hands to work this out?—there are the photos. It is the photos of the condemned men (and one woman) featured in the Benetton magazine insert that fill my mind as I wait there in the dark at San Quentin. Without Benetton, I would never have seen these faces, and now that I have seen them, no amount of cynicism about corporate motives can protect me from them. There is Joseph Amrine, forty-four years old and fourteen years on death row, looking bruised and wistful. There is Jeremy Sheets, twenty-six, with the straight brows and almond eyes of a medieval saint. There is Kevin Nigel Stanford, who has lived thirty-seven years, eighteen of them on death row, his soft, tan face glowing with religious resignation. Maybe some of them do look “scary,” as an acquaintance remarks, and it’s hard not to read the accompanying interviews without wondering “guilty or innocent?”—not that the interviews, which are a lot about loneliness and what it sounds like in prison at night, offer any answers to that.

The faces do, though, in their own way. Stare long enough and you see that each of them is saying: Look, violence is not a singular event, it is always a chain. It begins, in these cases, with a childhood of neglect and abuse; moves on to legally recognized crimes; then feeds itself further on the cruelty of imprisonment and capital punishment. One act of violence cannot cancel another; it can only propagate the chain. Capital punishment is just one more link, and a crucial one, because it draws so many more people into the cycle of violence—those who pay for the executions with their tax money, which is almost all of us, and those who fail to raise their voices in protest.

At the vigil I detect some North Face and probably Sears, but no visible Benetton. We have been standing a long time— almost a lifetime, or what’s left of it—when a rabbi takes the microphone and recounts Darrell Rich’s crimes in almost too much detail: the crushed skull, the bodies covered with bite marks, the little girl hurled from a bridge, already drowning in her own blood. Then he tells us why this matters and why it matters that we’re here—because every life is “a whole world”—or, as this bit of Jewish wisdom is sometimes put, “a miracle, a universe.” Part of the miracle of Darrell Rich is that, well into his imprisonment, he discovered that he was one-quarter Cherokee and took up Native American spirituality along with the name Young Elk. His last wish—denied by the state—was for a purifying sweat-lodge ceremony as a last rite. Now the hope, apparently shared by all the cross-bearers around me, is that he will be able to hear the music of the Indian drum circle that begins to play a few minutes before midnight, and that the sound will bear him safely into the spirit world.

I am trying, insofar as an atheist can, to invest these last moments with exalted thoughts. Maybe it will make a difference that we are here vigiling, and that Benetton runs its ads. Maybe Young Elk’s spirit will manifest itself above the fortress of San Quentin, clean at last and ready to redeem us. Maybe the victim’s relatives, who are inside right now watching him twitch as the poison enters his veins, will find peace now and even a wisp of forgiveness in their hearts.

But exaltation eludes me. The last few minutes feel like a demonic mockery of the countdown on New Year’s Eve. A ball’s going to drop, I can sense it coming, only it’s filled with some garbagy mix of regret and sorrow and so much waste. This, I finally decide, is not something you want to get on your clothes.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

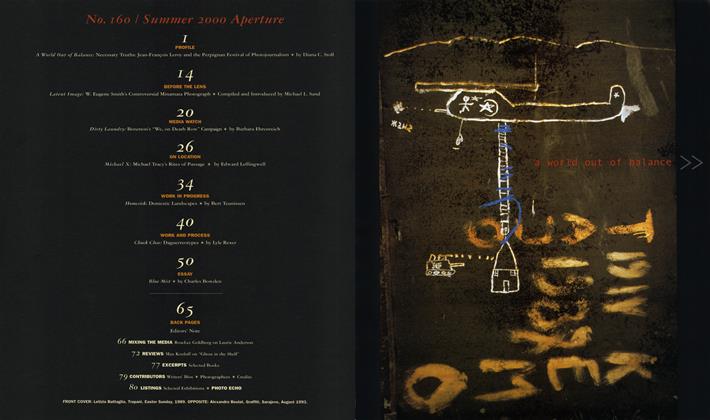

Essay

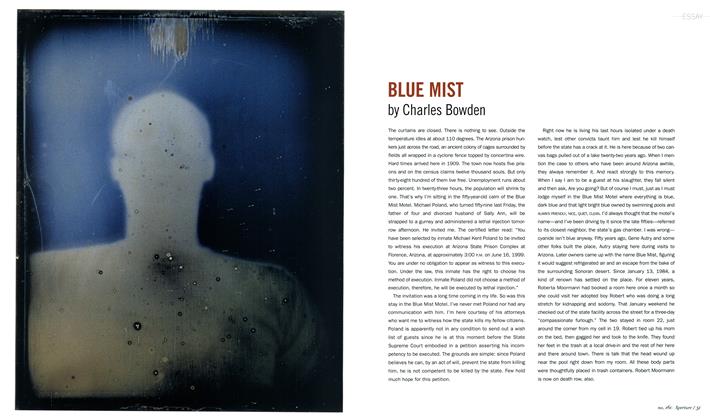

EssayBlue Mist

Summer 2000 By Charles Bowden -

Profile

ProfileA World Out Of Balance Necessary Truths

Summer 2000 By Diana C. Stoll -

Work And Process

Work And ProcessChuck Close Daguerreotypes

Summer 2000 By Lyle Rexer -

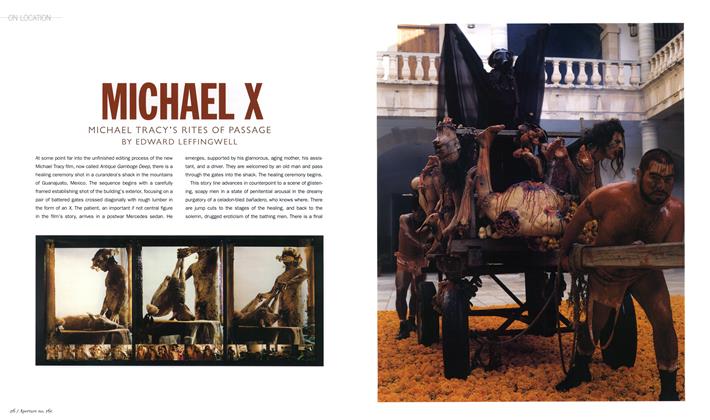

On Location

On LocationMichael X

Summer 2000 By Edward Leffingwell -

Before The Lens

Before The LensLatent Image

Summer 2000 By Michael L. Sand, Yoshio Uemura -

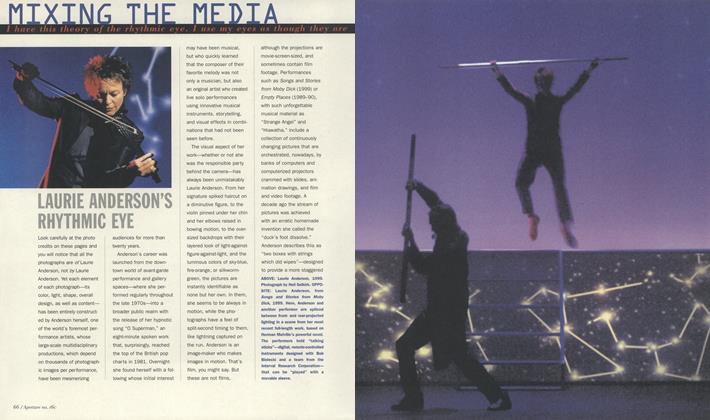

Mixing The Media

Mixing The MediaLaurie Anderson's Rhythmic Eye

Summer 2000 By Roselee Goldberg

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Media Watch

-

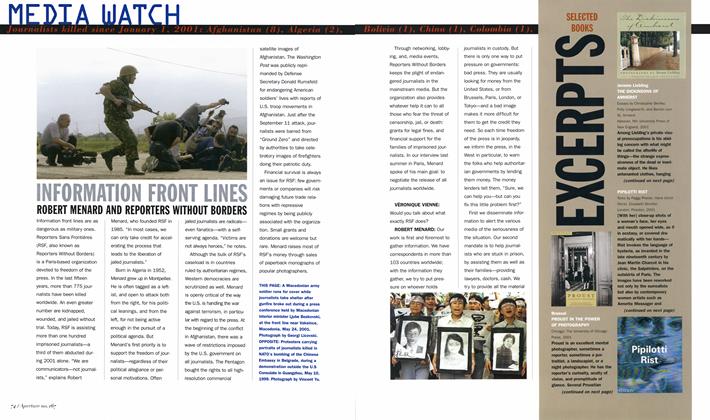

Media Watch

Media WatchInformation Front Lines

Summer 2002 -

Media Watch

Media WatchMichael Lesy: Death In Dubai

Fall 2010 -

Media Watch

Media WatchFallen Image

Fall 2003 By David Levi Strauss -

Media Watch

Media WatchRobot Dreams

Summer 2004 By David Levi Strauss -

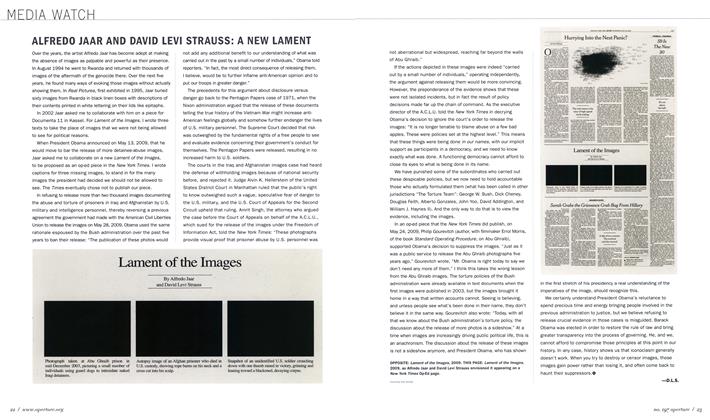

Media Watch

Media WatchAlfredo Jaar And David Levi Strauss: A New Lament

Winter 2009 By David Levi Strauss -

Media Watch

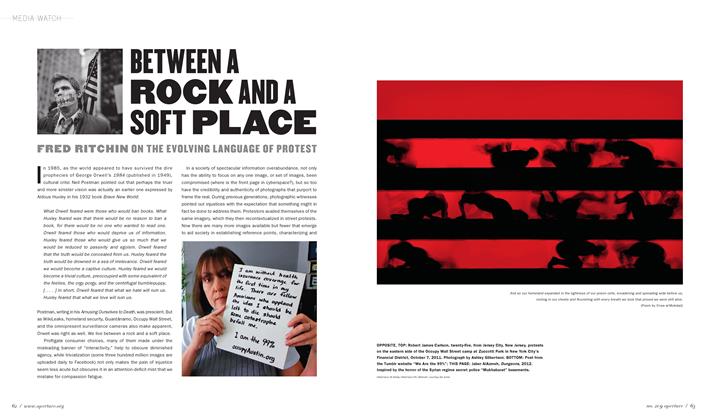

Media WatchBetween A Rock And A Soft Place

Winter 2012 By Fred Ritchin