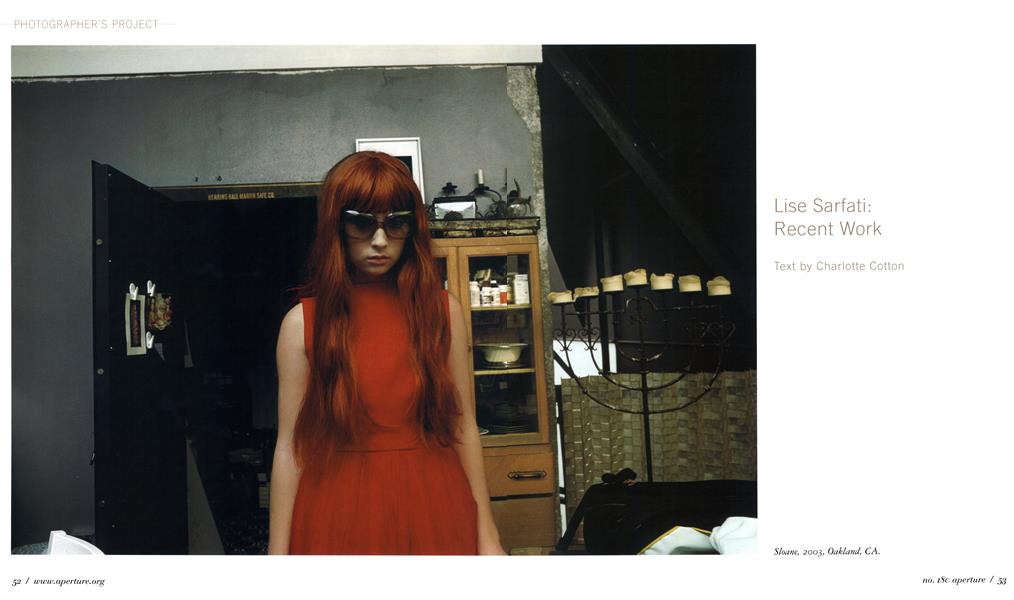

PHOTOGRAPHER'S PROJECT

Lise Sarfati: Recent Work

Charlotte Cotton

Sarfati acknowledges her attraction to lives that are being shaped by the paradoxes of where we come from and our aspirations of where we are heading.

I first became familiar with Lise Sarfati's work through her series of stunning photographs made in Russian cities, including Moscow, Norilsk and Vorkuta, in the 1990s. A fluent Russian speaker, Sarfati focused in this body of work on a kind of brutal "bohemia," and the intensity of life in the midst of post-Soviet decay. Those images proved her to be a sensitive and imaginative observer—of dread-filled, decaying industrial sites that serve as metaphors for chronic loss and waste, and of physically and socially ostracized young people. She showed us the inmates of an institution for young offenders in Iksha, patiently biding their time and their punishments. She followed the lives of Muscovite transsexuals undergoing gender redefinition. Throughout her work, Sarfati manages to create a loose and layered visualization that allows us, the viewers, to consider the complexities of any place or time, and one that triggers emotions and thoughts that move beyond the ostensible subjects of her photographs.

Sarfati has a capacity for shifting her photographic antennae and adopting multiple understandings of a place and its society. This was proven in her Russian imagery, as it is in her new series made in the United States, which is featured in these pages. Her work plays an important part in today’s debates about the uses and visual languages of socially engaged photography, in that Sarfati stubbornly resists “objectifying” the subjects that she is compelled to photograph. Her sense of curiosity is profoundly intuitive, and profoundly human. While we are used to viewing photographs of such subjects—including the legacy of the collapse of Communism in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, as well as the leitmotif that American youth can offer on the state of U.S. society—Sarfati consciously undermines any desire for or expectation of a single or defining perspective upon complex social ideas. Her photographs are much more concerned with activating within us a connection—via aesthetics and the intensity of her encounters with her subjects—with our world on a much more immediate and less quasi-informational way.

When I met with Sarfati recently, I made the mistake of describing her latest series as a selection of “portraits of American teenagers.” Sarfati called me on this oversimplification, pointing out that I was adopting a contraposition to these subjects. The term teenager, she suggested, is a categorization most often used by adults; and further, she believes that it is a largely market-driven label for a relatively new but powerful consumer group. It is not, at any rate for Sarfati, a term by which young people generally define themselves, nor is this idea what drew her to make this body of work. Sarfati’s photographic investigations into the young people that she encountered in shopping malls and streets and homes in the United States are not intended as projections of an adult onto a remembered period of earlier life. There is a strange practicality in Sarfati’s choice of subject matter: it is remarkable that this diminutive but very intense Frenchwoman—so out of place in the American cities where she traveled—found connections between her subjects’ “out-of-place” feelings and her own. The age range of those Sarfati photographed may be indicative of her recognition of their openness to requests (to them and their parents) to reveal this shared human experience. There’s little sense here that this series of images is the result of Sarfati’s confidently choreographing these young people into the usual photographic allegories of dislocation or disenfranchisement, regardless of the actual situations or states of minds of these individuals. If anything,

I suspect that what she has unlocked are mutual experiences of uncertainty—wrapped up in the mainly nonverbal, not-fundetermined or explained way in which she conducts each of her photographic portrayals.

In the realm of contemporary art photography, the depiction of teenagers has lately become a trope of sorts. This is not to suggest that practitioners of great integrity, such as Rineke Dijkstra and Hellen van Meene, haven’t contributed bodies of work of subtlety and meaning with their representations of youth. But this choice of subject has become a fairly easy symbol in much contemporary art photography, which perhaps cynically aims to invest itself with these values merely by representing youth as a fragile and fugitive moment in life. Sarfati’s subtle visualizations of the passions and frustrations of these young people—all on the cusp of adult responsibility—in Texas, Georgia, North Carolina, Oregon, and California, might be misread as the latest addition to photography’s recent near-obsession with this highly photogenic stage of life. Her subject, however, as she herself asserts, is not youth or “teenagerhood” per se, but the possibilities inherent in that period of life, during which emotions are close to the surface, reminding us of the individuality, vulnerability, and also fortitude that we all carry.

Sarfati’s American series began (typically for her) with intense research and preparation before any pictures were made; she is a prepossessed artist who internally questions and qualifies her reasoning for being drawn to a subject. She acknowledges her attraction to lives that are being shaped by the paradoxes of where we come from and our aspirations of where we are heading, and she understands that the investigation of such lives is most likely to be possible in sites of massive social shift (such as postindustrial towns in Russia) as well as in the physical manifestations of selfhood that young people consciously project. I imagine that all this allows her to be a relatively anxiety-free maker of photographs, attuned not only to her own motivations but also, in the case of these particular images, to the subtle and unexpected encounters she is liable to have, once she’s located the people and places that emit such emotive capacities. It is not entirely surprising that this fluid and substantial body of work was made over the course of only two journeys to America. It is an example of one of those uncanny experiences for photographers, impossibleto fully predict, simulate, orrepeat (with any certainty): the photographs, Sarfati says, just “happened.” She did not overtly orchestrate or attempt to define her subjects, but was carried by her own notion that, in the process of creating, she was exploring and understanding them. While her presence inevitably acted upon these young people, she also created the psychological space for them, in turn, to act upon her. This perhaps accounts for Sarfati’s success in representing these American youths as—individually and universally—the carriers of states of mind that center on willful self-determination—states of mind that are by no means exclusive to her chosen subjects.©

Her subject is not youth or “teenagerhood” per se, but the possibilities inherent in that period of life, during which emotions are close to the surface, reminding us of the vulnerability, and also fortitude that we all carry.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

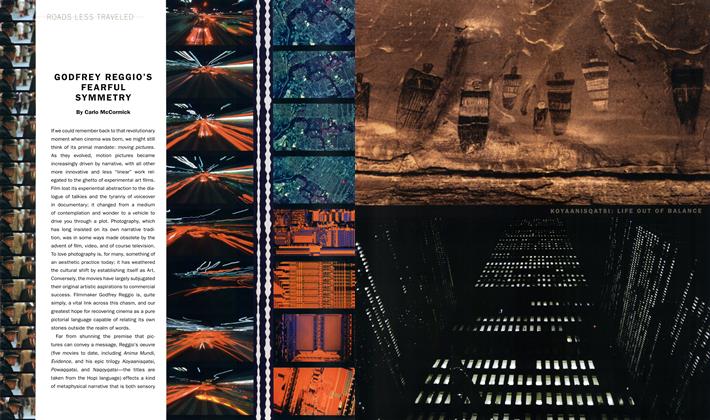

Roads Less Traveled

Roads Less TraveledGodfrey Reggio's Fearful Symmetry

Fall 2005 By Carlo McCormick -

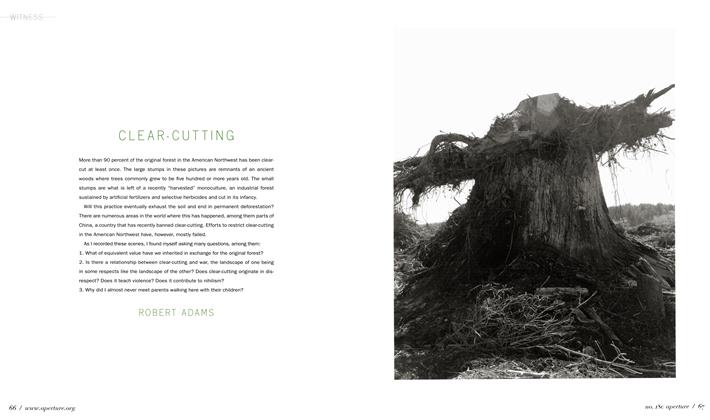

Witness

WitnessClear-Cutting

Fall 2005 By Robert Adams -

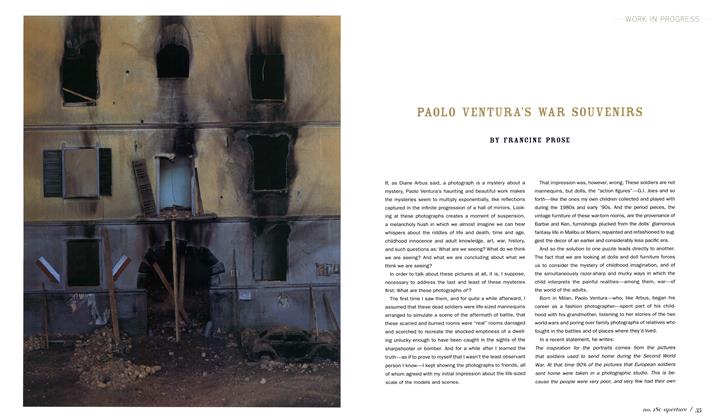

Work In Progress

Work In ProgressPaolo Ventura's War Souvenirs

Fall 2005 By Francine Prose -

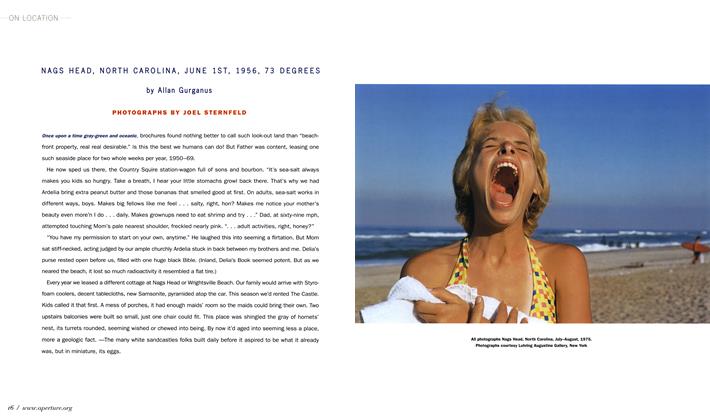

On Location

On LocationNags Head, North Carolina, June 1st, 1956, 73 Degrees

Fall 2005 By Allan Gurganus -

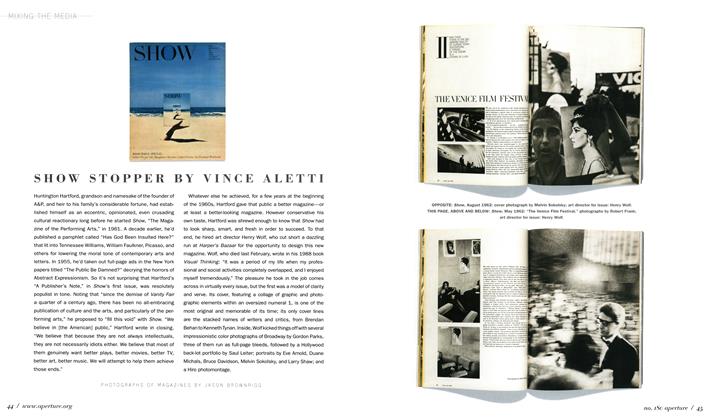

Mixing The Media

Mixing The MediaShow Stopper

Fall 2005 By Vince Aletti -

Remembrance

RemembranceKim Zorn Caputo (1952-2004)

Fall 2005 By Richard Misrach

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Charlotte Cotton

-

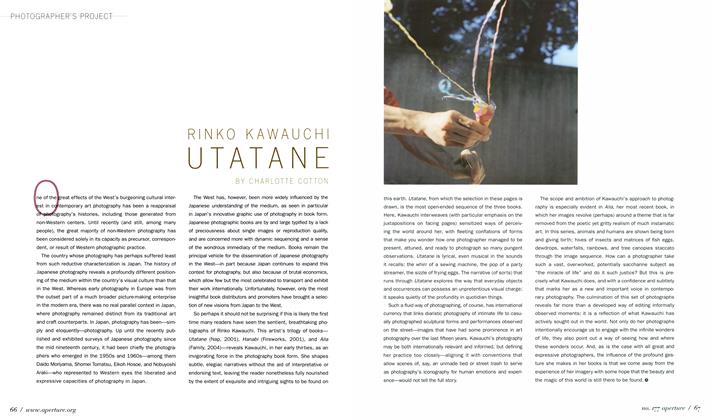

Photographer's Project

Photographer's ProjectRinko Kawauchi Utatane

Winter 2004 By Charlotte Cotton -

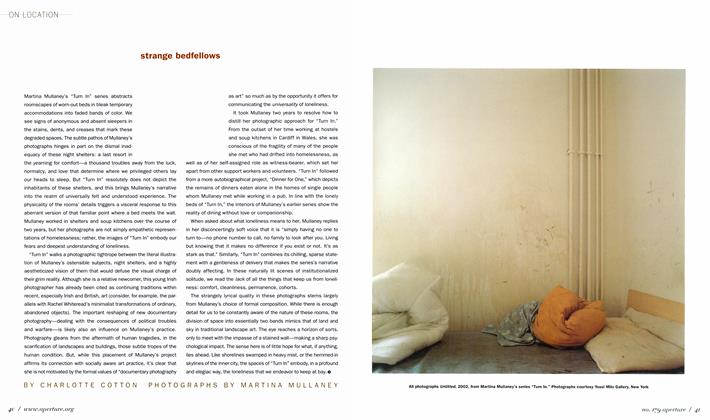

On Location

On LocationStrange Bedfellows

Summer 2005 By Charlotte Cotton -

Books

BooksAnna Fox: Photographs, 1983-2007

Fall 2008 By Charlotte Cotton -

Words

WordsNine Years, A Million Conceptual Miles

Spring 2013 By Charlotte Cotton -

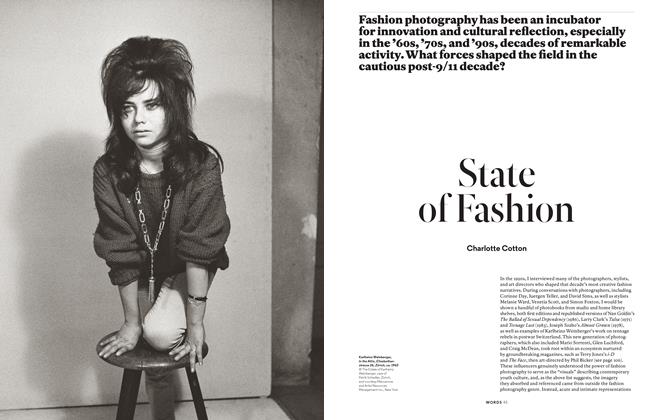

Words

WordsState Of Fashion

Fall 2014 By Charlotte Cotton -

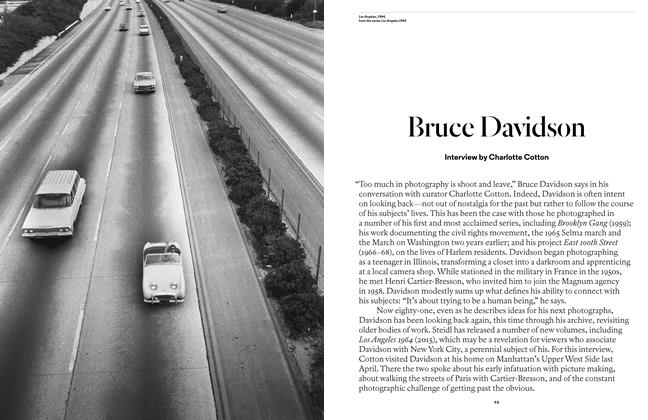

Bruce Davidson

Fall 2015 By Charlotte Cotton

Photographer's Project

-

Photographer's Project

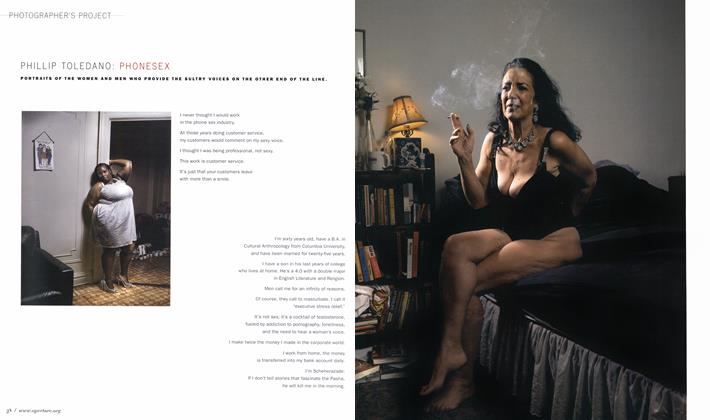

Photographer's ProjectPhillip Toledano: Phonesex

Winter 2008 -

Photographer's Project

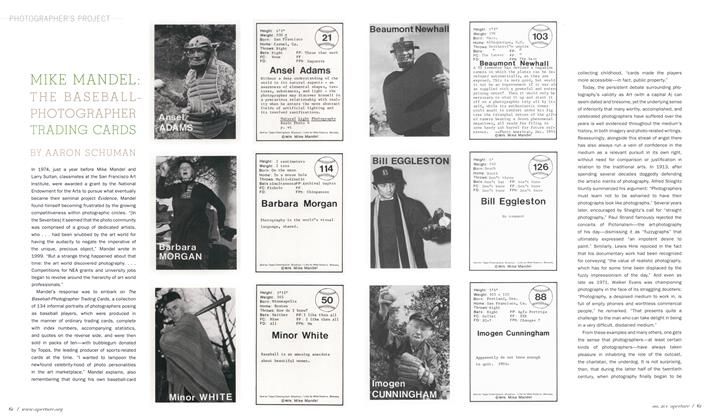

Photographer's ProjectMike Mandel: The Baseball-Photographer Trading Cards

Fall 2010 By Aaron Schuman -

Photographer's Project

Photographer's ProjectThe Darkroom Rip

Fall 2007 By Martin Parr -

Photographer's Project

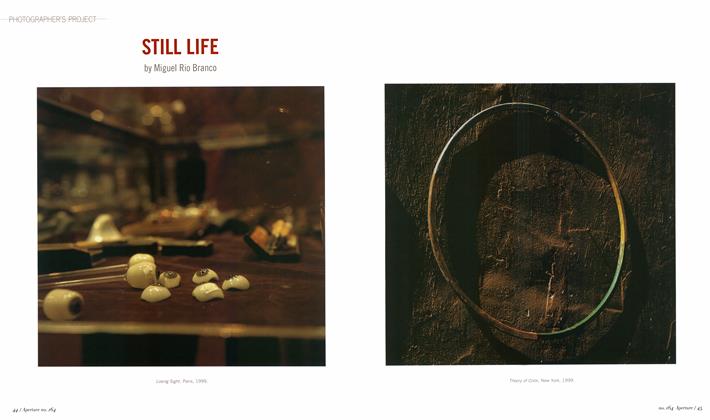

Photographer's ProjectStill Life

Summer 2001 By Miguel Rio Branco -

Photographer's Project

Photographer's ProjectVenice 1943

Summer 2011 By Paolo Ventura -

Photographer's Project

Photographer's ProjectLavina

Spring 2011 By The Editors