ArtSeen

Georgia O’Keeffe: To See Takes Time

On View

Museum Of Modern ArtTo See Takes Time

April 9 – August 12, 2023

New York

In the eyes of the profound American artist Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986), a single artwork can’t always fully express the complexity of its subject: sometimes it takes a few tries. Up now at MoMA is a wonderful expansion of that idea in Georgia O’Keeffe: To See Takes Time, featuring more than 120 works on paper spanning five decades of the pioneering artist's career. Organized chronologically throughout three galleries, the exhibition highlights O’Keeffe’s artistic process via her repetition of forms and colors to create rhythmically dynamic compositions.

The exhibition opens with a trio of charcoal drawings that are possibly the most abstract forms on view. In First Drawing of the Blue Lines, Black Lines, and Blue Lines X (all 1916), O’Keeffe experiments with the simplest of structures—a line—and sees how far she can stretch both the concept and the pigment. Each of the three drawings depicts two lines, one jagged, the other straight, above a puddle of color, either blue or black. The pressure with which O’Keeffe traced against the paper is evident through the lighter, more diluted colors and the darker, more pigmented ones. The intimacy we can see in O’Keeffe’s brushwork sets the tone for the rest of the show; we are introduced to a new side of O’Keeffe, one at her rawest and purest thinking.

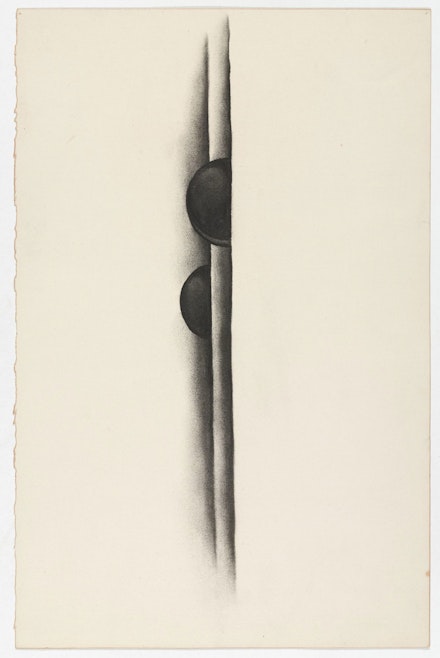

Nearby is a series of charcoal drawings in black and white, where we begin to see early abstract formations of the geological and botanic motifs that the artist is known for. Within this series on the south wall is Special No. 9 (1915), which O’Keeffe called a drawing of a headache. In this work, the artist pushes the limits of both the medium and her abstract forms to emit emotions and represent the physical sensations of a migraine: pounding, trembling, and throbbing are all seen as undulating lines, cloudy forms, and sharp points.

Growing up on a farm in Wisconsin, O’Keeffe was determined to make it as an artist, and as a woman, that was no easy feat. O’Keeffe traveled to Virginia, South Carolina, Texas, and New York, working as an art teacher by day and making these abstract works on large sheets of paper at night. As O’Keeffe moved around, so too did her inspirations and her vision. Works from her time in Charlottesville, Virginia, during the summer of 1916 show a highly varied range of tones and textures and find O’Keeffe trying out techniques to realize new ways of seeing. In Blue #1-4 (all 1916), the paper is dominated by shades of blue that depict motifs from the Appalachian Mountains. Perhaps two rolling hills were met by a plain, and in O’Keeffe’s vision, these become two large curves that bleed into one another while simultaneously being struck by three decisive bands of blue. Here, the paper itself becomes an additional medium; its reaction to the watercolor created a ripple-like effect when it dried, showing both its ability to adapt and shape-shift, as well as its fragility and ephemerality.

O’Keeffe was an artist who was deliberate and intentional, especially when it came to her materials. These experimental techniques with paper, ink, water, and color begin in the first room and blossom in the remaining galleries. In the hallway, there is an homage to her tools with a vitrine displaying her brushes, charcoals, pigments, and pastels. An archival image of Georgia with her watercolors helps the viewer imagine the artist, putting a face to a name, and what it was like for her to view a sunset in Texas or a highway in Arizona and try to capture it—its likeness, its feeling, its temporality—in multiple images. For O’Keeffe, traveling and the changing landscapes were worth capturing at a moment’s notice, and paper became her most valuable asset to document the views. From a dark purple rainstorm in Maine, to highways that look like veins or tree trunks seen from an airplane, to even drawing her friend Beauford Delaney, O’Keeffe dedicated herself to drawing what she saw.

In the center of the second gallery are two large works: Over Blue (1918), a pastel drawing, and Music–Pink and Blue No. 1 (1918), an oil painting. The two works are similar in composition, both abstractions of folds arching over one another that bend around a deep blue form. The pastel is most likely a sketch for the final painting, but I found myself struck, and stuck, with the pastel more so than the oil painting. The purity of the colors in the pastel is achieved by O’Keeffe’s decision to not use white pastel, which can easily make the colors go muddy. In the painting, she experiments with a great deal of white paint, creating a more subdued and harmonious image. But the pastel is utterly vibrant: the blue void feels three-dimensional and alive.

Just as O’Keeffe said, “To see takes time, like to have a friend takes time.” The longer I spent with the pastel, the more I felt like I was becoming acquainted with the inside of O’Keeffe’s mind, dwelling in the depths of her colors.