At the foot of huge Postavarul Mountain and the Poiana Brasov ski station, Brasoc unquestionably remains Transylvania’s most fascinating city, with its citadel, ramparts, and medieval center, the latter today closed to cars.

The late-nineteenth-century synagogue here was sacked during the Second World War by pro-Nazis locals. It was rebuilt in 1944 but seriously damaged again in a 1977 earthquake. It was then restored once more, and now serves as a center for what remains of Jewish life in this city. A kosher restaurant, retirement home, mikvah, and community housing are all located nearby. Several hundred Jews, the majority of whom belong to the Reform tradition, still live in Brasov.

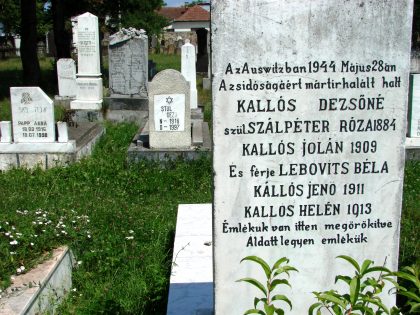

Remember that in times past. Orthodox Jews practiced agriculture in the remote region of Maramures, following the example of their Romanian and Hungarian neighbors. They have all but disappeared. Memory of them is gradually fading, along with that of their protectors and friends, the late Hapsburgs. There’s also a Jewish cemetery in town.

The Grand Synagogue of Sibiu has been declared a historical monument by the Romanian Academy.

With its elegant interior and Renaissance facade enhanced by Gothic elements, it remains a popular tourist attraction. The city also has a Jewish cemetery.

The first Jews probably settled in Timisoara in the 17th century. Gravestones were found in the city dating from that era. At the end of the conflict between the Austrians and the Turks, a Jewish Community life quickly developed. Both Sephardic and Ashkenazic.

Places of worship were created but also cultural establishments as well as schools. Facing regular waves of anti-Semitism, the results of the Holocaust as well as massive exiles, the Jews which numbered 13000 in 1947, are only a few dozens today.

Among the important figures of the religious life, Rabbi Erno Neumann ensured a continuous religious life after the war until his death in 2004.

In Timisoara, the Temple of the Citadel was modeled after the famous synagogue on Dohány Street in Budapest. It was consecrated in 1867 with Emperor Franz Josef in attendance. Like the two other synagogues still active in Timisoara, it rivals the Orthodox Christian cathedrals in beauty, bringing together Baroque, Byzantine, Gothic, and Moorish architectural elements.

The Fabric synagogue, built in a Neolog style which can be found used frequently in the construction of the country’s places of worship, was inaugurated by the town’s mayor in 1899. Hungarian architect Lipot Baumhorn built many synagogues in Eastern Europe, as well as other types of monuments in the city of Timisoara itself. A massive and original building, charged with a rich history, the synagogue is neverthell in a serious state of degradation.

The Iosefin synagogue carries the name of the neighborhood it was built in by the Orthodox community in 1895. The city also has a Jewish cemetery.

At the northern border of Transylvania lies Sighet Marmatiei, unquestionably the region’s most original and charming little city, where Romanian, Hungarian, Roma and Ruthenian populations all coexist. Nobel Peace Prize winner Elie Wiesel was born in this Hasidic township.

Jews settled in this town, located in the region of Maramures, in the 17th century.

The Jewish population grew from 39 persons in 1746 to 4960 in 1910 and 10144 in 1941, about 40 % of the local population.

It quickly became an important center of religious movements, especially Hasidism. Among the rabbis are Judah ha-Kohen Heller, Zevi b. Moses Abraham, Hananiah Yom Tov Lipa Teitelbaum and Samuel Danzig. The latter one headed the Sephardic liberal community.

The religious and cultural Jewish life was very rich even if most of the Jews lived in poverty. Jewish schools, yeshivot, newspapers and libraries were present. Many cultural personalities emerged in the city. Among them the author Hirsch Leib Gottlieb, Yiddish poet J. Holder, Yiddish author J. Ring, pianist Geza Frid and of course author Elie Wiesel. Jewish plays and artistic gatherings took place.

Between the two world wars, the Romanian Iron Guard regularly threatened the Jews. After the annexation of Transylvania by Hungary in 1940, Jews were conscripted for forced labor and later put in a ghetto from which 12000 were deported.

After the war, about 2300 returning Jews from Sighet and surrounding areas tried to recreate a Jewish community. But only 250 remained there in 1970.

Since 1989, there has been a renewal of Jewish heritage interest by Jews and local authorities. Attempts given more light by Elie Wiesel’s visits to his hometown.

Among the monuments to be visited there are the Sephardic synagogue, also known as the Klaus Wijnitzer synagogue. While Sighet originally had about twelve, this is the one remaining. Built in 1902 in a Moresque style, it was recently restored.

Another famous place is the Elie Wiesel’s Memorial House welcomes many visitors. The place where the author and his family lived is visited by students and teachers, local ones but also from all over Europe. Programs and exhibits are organized there throughout the year.

The Kahana Court, located on the Gheorghe Doja Street, previously known as the Yiddish Gass. Named after an important local Jewish family, it was a major centre of the city’s Jewish life, housing a school, shops and cultural encounters. The Tarbut Foundation, which highlights the Jewish Heritage in the region of Marmarus, especially in the city of Sighet, has its offices there today. Tarbut organizes trips, educational programs and the restoring of monuments linked to that heritage.

The Drimer House in the Sighet Village Museum, where old homes of people from all backgrounds are shown, named after its rabbi was also used as a synagogue.

An important center of the Hasidic movement, Sighet is also where many of its rabbis are buried. The Jewish cemetery is visited by tourists and pilgrims honoring those rabbis.

Erected by Holocaust survivors, a Memorial Monument was built on the former location of a synagogue destroyed during the war. Commemoration services are held there regularly during the year. A plaque commemorating the departure of trains to the camps during the Holocaust can also be found at the local train station.

Our interview with Peninah Zilberman, founder and CEO of the Tarbut Foundation.

Jguideeurope: How do you perceive the evolution of interest concerning Jewish heritage in Romania?

Peninah Zilberman: Generally speaking, there is a revival of Jewish Heritage across Eastern European countries who were under the Communist Regime.

I have been coming to Romania since 1998, not too many people used to come and visit-there were still many issues of visa etc., to deal with; However I must say that in the past 5 years, there is a greater interest of Jews to come with their extended family and visit their hometowns, cemeteries, synagogues where members of the family used to pray and so on. As the survivors are leaving us, visits are beneficial for their relatives.

At the same time, the local Jewish Communities in the major cities e.g. Bucharest, Oradea, Cluj, Iasi and Timisoara are developing Jewish programs for all generations… children to seniors. Many of the synagogues are being restored, attracting tourists of all faiths. Timisoara has been chosen to be the EU Cultural City of Europe in 2021. Its synagogue is almost finally restored, and programs are being organized there.

What are the places most visited in Sighet linked to that heritage?

The places a tourist can visit are the synagogue, the Jewish cemetery, the monument in memory of the Jews who were murdered at the various camps, Elie Wiesel Memorial House, Tarbut headquarters at the Kahana (a famous Jewish family in Sighet) Court, The Jewish Gasse (Street), pointing out various houses where important leaders of the Jewish Community used to live, the ghetto area and the train station from where the Jews were deported.

Can you tell us a bit more about Elie Wiesel’s link to the city?

The late Prof. Elie Wiesel (1928-2016) was born in Sighet and lived there until he was deported with his family during May 16-22, 1944. His family house was transformed in 2003 into the local Jewish Museum (Memorial House). The objects shown in the museum belonged to the many Jews who lived in the city or the Maramures Region.

What are today’s main purposes of Tarbut?

Tarbut has 2 major objectives: First, offering genealogical research followed by “Family Roots Journeys” for all generations. These Journeys usually take place between May and October. We mainly cover the regions from where the Jews were deported (Northern Transylvanians, Bucovina to Transnistria, and Iasi), and remembering the Pogroms. Our second aim is to teach the local high school students about the Jewish history in the region, deportations and the Holocaust. We teach it through the Arts (music, art, writing, plays) and trips to Auschwitz.

Are you organizing special events for 2022-23?

Tarbut is under Renewal mode following almost 3 years of hiatus except of Zoom programs. A number of upcoming “Family Roots/Routes Journey” take place over the summer. People want to catch the moment, we are pleased to accommodate and deliver as many as possible. European Jewish Heritage Days will be launched in mid-September in a few localities across Maramures. May 2023 a major “Yiddish Festival” is being planned in cooperation with the Jewish National Theatre in Bucharest. As well as in other Romanian major cities. In addition we will renew our special high school and Educators seminars and cultural activities. Plans are underway for a special “All Generations Gathering & Commemoration “ marking the 80th Anniversary to the Jewish Deportations May 16-22, 1944 from Sighet.

You can contact us at Peninah@ftsighet.com or check the website for upcoming events www.ftsighet.com

The community of Oradea, exterminated during the war, dates back to the 15th century. Today, a reformed synagogue still works for the few Jews in the city.

The Jewish Museum of Oradea was inaugurated at the end of 2018 in the recently restored synagogue and reconsecrated Hinech Neorim. The museum, which presents the history of the local Jewish community and that of the Holocaust, is a branch of the Municipal Museum. On the ground floor of the museum, there are explanatory panels and objects that trace the history of this city that was home to one of the most important communities in Transylvania. The permanent exhibition explains how the community participated in the building of the city. It is believed that the presence of a Jewish community dates back to the 15th century. In the eighteenth century, the community is organized. On the eve of the Second World War, Jews made up about a third of the population of Oradea – out of a total of 30,000.

Oradea is known for its many art nouveau buildings, many of which were built by Jewish architects and / or belonged to the Jewish elite of the city. This is particularly the case of the Black Eagle House, built in 1908 by the Jewish architects Marcell Komer and Dezso Jakob, the same who were behind the Subotica synagogue in Serbia.

The first floor of the museum features a permanent exhibition and Holocaust memorial. There is a symbolic railway rail and the names of the 30,000 local victims.

As for the synagogue that houses the museum, it was built in the late 1920s by the architect Istvan Pinter. It is the most modern of the last six synagogues still visible in Oradea today. The building belongs to the Jewish community, but it is the heritage department of the city that has been in charge since 2016.

The magnificent Zion synagogue on the banks of the Cris River served the neologue community. It was built by the city’s architect, David Busch, in 1878. It was rededicated in 2015, after a complete renovation. It now houses a cultural center. Finally, the Great Synagogue of the city was reconsecrated in September 2017, after 8 years of restoration.

You can also visit two other synagogues in Oradea: the Teleki synagogue, built in the 1920s; and the Chevra Sas synagogue, it was built in 1822. It now houses a community of 500, the largest in Romania.

Cluj is today Transylvania’s most important city. The Jewish presence became significant here only starting in the late eighteenth century. The community, divided between those of Orthodox faith and Reformists, was uniformly annihilated in Auschwitz following imprisonment within the city’s ghetto.

Only a few dozen Jews live in Cluj today, the rare survivors of the Shoah here having mostly emigrated to Israel in the years following the war.

Make sure to visit Cluj’s very beautiful synagogue, referred to as the Temple of the Deportees. Built in 1866, transformed into a warehouse under the Horthy regime, and later damaged by the Nazis during their retreat, it has been subject to a number of restoration projects.

There are ancient Jewish cemeteries in Cluj, among them the ones located on the streets of Turzii and Soimului.

The city of lasi, Moldavia’s capital since the sixteenth century, is surrounded by little towns of pastel-colored houses and whitewashed, thatched cottages.

Long ago, places like Bivolari, Harlau, Podul Iloaei, and Târgu-Frumos were abandoned by their Jewish inhabitants.

In the 1920s, it was lasi that contained the eastern region’s most important Jewish community. Populated by artisans, kabbalists, merchants, and Talmudists, the city counted 43000 Jews at the time, or half its total population, and no fewer than 112 synagogues.

It was here that, in 1876, Abraham Goldfaden staged his first production, the foundation of European-Jewish theater. French-language poet Benjamin Fondane was born here as well, in 1898. It was also in lasi that some of Romania’s most virulent anti-Semitic movements developed. lasi was thus chosen, on 8 November 1940, as the seat for the Iron Guards, a Fascist and fiercely anti-Semitic organization outlawed after its January 1941 uprising against General Ion Antonescu. This very dictator, after putting a stop to the Bucharest pogrom, turned around and supported in June of the same year the massacre of some 12500 Jews in lasi and Dorohoi (a tragedy described by Curzio Malaparte in his remarkable book Kaputt).

What remains today of lasi’s Jewish community, which once rivaled the communities of Poland, Ukraine, and Russia? In the late 1960s, fewer than 2000 families still lived in lasi, and only eleven synagogues remained here. Today, only a few dozen people belong to this community, which runs the kosher restaurant and the Museum of History and Art.

The Grand Synagogue is the oldest one in the region. Built in 1671 on the order of Rabbi Nathan Hanover, it was first restored a century later, then modernized in 1864. Proudly blending Ashzenazic, Byzantine, and Sephardic architectural elements, it attests its kinship not only to ones in Bohemia, Poland Ukraine, and Russia, but also to those in Greece and Bulgaria.

Note that gravestones from the old Jewish cemetery on Clurchi Street have been transferred to the cemetery on Pàcurari Street, where a monument commemorates the victims of the June 1941 pogrom.

Three identities, one destiny

Benjamin Wechsler, Fundoianu or Fondane?

Three distinct identities -Jewish, Romanian, and French- struggle for primacy in the work of this problematic poet. It was the first of the three that brought about his death in Birkenau at the end of May 1944.

Born in 1898, poet, essayist, philosopher and filmmaker Benjamin Fondane left his native city, lasi for paris in 1923:

“Locked in a memory like an obscure line of poetry

In an emptiness run through with flags and dreams

I await your arrival, trumped of Catastrophic Fear”

he wrote in 1922. Imprisoned at Drancy in 1944, he refused a pardon offered him after his wife and friends (Emil Cioran, Stéphone Lepanscu, and Jean Paulhan) intervened on his behalf. He instead chose to accompany his sister on her final journey.

The city of Galati has been a major Romanian trade hub since the seventeenth century. In 1868, it was the theater for acts of vandalism against Jews following accusations of their having committed ritual murders.

The imposing “Synagogue of Artisans” was the only temple to remain standing out of the twenty-nine that were active here during the 1930s.

Built in 1875, the synagogue was reinaugurated in 2014. Aside from the synagogue, the city has one kosher restaurant and a Jewish cemetery.

Jewish Bucharest has almost completely disappeared. Of a population estimated at 158000 souls in 1948, there remain only 2000 people today. Spread out across the four corners of the capital, the are doubtlessly too old or in too precarious an economic situation to contemplate emigration.

The old Jewish quarter

The old Jewish quarter was located near the Unirei (Union) Square on the other side of Sfanta Vineri Street. To the southeast, Dudesti and Vàcàresti streets resounded with the joys and color of Jewish life. These streets no longer exist. In their place stretches a vague, rubble-strewn terrain the locals call “Hiroshima”. Ceausescu reduced it all to nothingness in order to build a mad, improbable “City of the Future”. A lone house attests to the Jewish presence in these parts: the Jewish State Theater. This is where actors -non-Jewish ones, for that matter- continue to learn Yiddish and interpret works by the great jewish playwrights in the original language.

Synagogues

Few active synagogues remain in Bucharest. At the turn of the twentieth century, however, the city contained at least sixty-six of them, Sephardic as well as Ahkenazic.

The Choral Temple remains the city’s most important religious site today. Built in 1866 according to a design by the architects Endele and Freiwald in the Viennese style (just like the synagogue on Dohány Street in Budapest), it was rebuilt in 1933 and then in 1945, after it was vandalized by the Iron Guards during a January 1941 pogrom.

The Grand Synagogue, which catered to the Ashkenazic community, was built in 1846 by a congregation of Polish Jews. It stands on Vasile Adamache Street, one of the oldest streets in the capital, alongside miraculously preserved low houses. In 1992, this synagogue was transformed into a museum. Here you will find religious objects, documents, and precious incunabula that retrace the history of Romania’s former Jewish communities. In the center sits a statue in honor of the tens of thousands of Trans-Dniestrian Jews, victims of pogroms and deportations. During the war, 200 000 Transylvanian Jews were sent to Auschwitz by the Hungarian authorities, never to return. The Mamulari Synagogue hosts as well a Jewish Museum.

Located in a lively street overlooking Bulevardul Maghero, the Yeshoah Tova synagogue is Bucharest’s oldest place of worship, dating back to 1822. Services are held at the entrance on the Sabbath and on Saturday mornings at 9am.

The cemetery

The austere Sephardic cemetery Calea Serban Vodà also bears the scars of the pogroms and mass exterminations suffered by Romanian Jews in Moldavia, Bukovina, Bessarabia, and Trans-Dniestra. Another Sephardic cemetery is located in the Giurgiului district. Finally, the Filantropia cemetery houses a small oratory.

Jewish life today

A visit to the sober Shoah Memorial is advised. The Museum opened in 2009, as Romania only very recently started acknowledging publicly its responsibility in the Shoah.

The town’s community centre offers weekly activities and also runs the country’s only digital Jewish radio station: Radio Shalom Romania. The dynamic Federation of Jewish Communities of Romania publishes -in Romanian, English, and Hebrew- the excellent bimonthly Réalitatea evreascà (Jewish reality). The catalog of Hasefer, perhaps the only remaining jewish publishing house in eastern and Central Europe, contains works by Sholem Aleichem, Martin Buber, Bernard Malamud, and Simon Dubnov, as well as those by Romanian-born authors Elie Wiesel, Carol Lancu, and Mihail Sebastian.

For the purposes of this tourist and cultural guidebook, we will not linger on the extermination camps, which are “documents to barbarity”, as Walter Benjamin put it, and not to culture. Yet we must mention some of them at least, as we seek to comprehend the incomprehensible, to grasp through their images that which ultimately cannot be grasped.

In Sobibór, there are in a sense two different villages. Sobibór proper is a sleepy, peaceful little town with a small Catholic church along the Bug. To see what remains of the camp, you need to go to Sobibór-Stacja, Kolejowa (Sobibór Railway Station), a mile or two from here, accessible only through the forest. The forest is huge, and one must admit, magnificent. If, as Claude Lanzmann put it, every landscape in Poland breathes the Shoah, this is especially true around here.

On the other side of the forest, the road is blocked by a barrier. A sign reads SOBIBÓR, in the station, another sign reads WAITING ROOM. Besides the station agent and a woodworking company, the place is completely desolate. It was here that for a year and a half, from March 1942 to October 1943, convoys arrived from Poland and beyond, packed with 250000 Jews who were immediately gassed. All that remains today are the ramp, a monument, and a small museum. A short walk to the site of the camp itself yields only a sort of circular tumulus.

The site was well documented in the film Sobibór, October 14, 1943, 4 P.M. by Claude Lanzmann.

Jews began settling in Wlodawa in the seventeenth century. By the turn of the twentieth century, they numbered 3670 (66% of the population), then 4200 (67%) in 1921, and 5650 (75%) in 1939. The Germans created a ghetto to which they deported 800 Jews from Kraków and 1000 from Vienna, before exterminating them all in the camp near Sobibór, a mile or two from here in the forest, beside the Bug River.

Wlodawa contains one of Poland’s most important Baroque synagogues. Built in 1762, it features a square shape with a high upper floor and sloped roof. Destroyed during the occupation, it was restored after the war. A scene from the film Shoah by Claude Lanzmann takes place here: the synagogue appears in close-up while the director interviews a witness from the era, Pan Filipowicz.

Shoah (excerpt)

“There was a synagogue in Wlodawa?

Yes, there was a synagogue and it was very, very beautiful. When Poland was still controlled by the czars, the synagogue was already here. It is even older than the Catholic church. It is no longer active. There are no more believers around here.”

Claude Lanzmann, Shoah (Paris: Gallimard-Folio, 1997).

The city of Jozefów possesses a beautiful late-seventeenth century synagogue. It can be seen almost immediately upon arriving in the village, on the right and set back a bit in relation to the city center and the intersection of Górnicza and Krótka streets. It was rebuilt in the 1990s and converted into a public library with one distinctive feature: upstairs, a doctors office and hotel are located in the former women’s gallery.

A jewish community sprang up in Szczebrzeszyn in the sixteenth century, while the synagogue was built here in the seventeenth century. In the nineteenth century, the community experienced important growth, jumping from 1083 members (31% of the population) in 1827 to 2450 (44%) in 1897; it also became a center of Hasidic influence centered around the tsadik Elimelech Hurwitz. Before the war, 3200 Jews lived in Szczebrzeszyn; they were all deported to Belzec in May 1942.

Szczebrzeszyn is today a small, tranquil city, with a Catholic church and city hall downtown.

Right near the central square (on Sadowa Street), you will see a tall, distinctive building, squarely set with a sloping roof: this is the synagogue, today a “house of culture”. A plaque indicates that it is one of the oldest synagogues in Poland. It is also protected as a national monument. It was burned down in 1940 and rebuilt in 1957.

A path behind the synagogue leads to the Jewish cemetery, which has been swallowed up by the forest. You will have to clear your way through the ferns and shrubs to visit its many very old graves. In the center, a monument commemorates the execution of the Jews of Szczebrzeszyn in this very spot.

Zamosc is a magnificent example from the Polish Renaissance era. Built in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries by Italian architects in the service of Kings Sigismund and Casimir, the city offers a distinctive architectural unity, with its wide-stepped city hall, central square lined with beautiful Renaissance and Baroque mansions, and its crisscrossing of old, narrow streets arranged around the city wall and gates.

The Jewish community began settling here in 1588, after the waycode Jan Zamojski allowed Sephardic Jews from Italy, Spain and Turkey to come to his city, and even granted privileges. In the seventeenth century, they arrived in even greater numbers. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the Haskalah developed in Zamosc, the Jewish enlightenment and emancipation movement imported from Berlin and Vilna (Vilnius). When Poland was divided, Zamosc fell within the Russian Empire. Yiddish writer Itzhak Leybush Peretz was born here in 1851, and he remained for thirty-six years before moving to Warsaw. The revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg, murdered in Berlin in 1919, was also born here, in 1870. In 1856, 2490 Jews lived here; in 1921, they numbered 9383 (or 60% of the population) and, just before the war, 12000. They were all deported to Belzec in April and May 1942.

The former Jewish quarter was located around Zamenhofa and Pereca streets. The synagogue at 9 Zamenhofa Street was built between 1610 and 1620 in late Polish Renaissance style, like other important buildings in Zamosc. Destroyed during the war, restored in the 1950s and 1960s and again in 1980, it still boasts its Renaissance-style gate. On its exterior walls, a frieze bears images of envelopes, but this is not a post office: it is a public library.

The Jewish community house (dom Kalhany) and a mikvah dating to 1877 are located beside the synagogue.

Itzhak Leybush Peretz

Itzhak Leybush Peretz (Icchok Leib Perec in Polish) is considered, with Sholem Aleichem and Mendele Moykher Sforim, one of the classic authors of Yiddish literature. Born in 1851 in Zamosc, he began writing in Polish, then Hebrew, but, in 1888, settled on Yiddish, at the time considered merely a jargon, mameloshn. He spent more than ten years here working as a lawyer, then set out for Warsaw, where he strove to define Yiddish culture and founded a daily newspaper, Der Veg. His funeral procession in 1915 included 100000 people. French novelist Georges Perec, whose parents hailed from Lubartów near Lublin, maintained he was a great-grandnephew of Peretz (see W, or the Memory of a Childhood [London: Harvill Press, 2000]).

If one stop along the road from Lublin to Warsaw is a must, it is in the city of Kazimierz Dolny on the Vistula, first because it is a tourist city, with old houses, a magnificent rynek lined with Renaissance or Baroque facades, a large church, and castle, but also because it has been marked by an important Jewish presence, of which there remain a few remarkable traces, most notably the eighteenth-century synagogue, just behind the large square at 4 Lubelska Street. Rebuilt after the war, it serves as a cinema today. On one of the walls, a plaque recalls the memory of 3000 Jews of Kazimierz Dolny murdered by the Germans.

When you leave the city, if you take the road toward Opole Lubelskie, you can see what remains of the former Jewish cemetery on Czerniawy Street. On the hillside, overtaken by the forest, several beautiful gravestones still stand, as well as a moving roadside monument made from hundreds of peices of destroyed tombstones.

An important city in eastern Poland, Lublin has preserved a very picturesque old quarter that offers a glimpse of what life was like here in the seventeenth century, with a city hall in the middle of the rynek, a Dominican church, fortifications, and various city gates. Lublin also features a castle surrounded by a park plucked straight out of a tale from The Thousand and One Nights. The castle and its park are accessible from Zamkowa Street.

Large numbers of Jews began settling in Lublin in the fourteenth century, first in the Kazimierz Zydowski district, later near the castle. The Grodzka gate was called Brama Zydowska (Jewish Gate). The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were the high point of Lublin’s Jewish community: a Hebrew press was founded in 1547, followed by a second one in 1578; the town also featured a renowned Talmudic school directed by major figures of the era -Solomon Luria, Mordecaï Jaffe, and Meir ben Gedaliah. (It is also where Moses Isserles completed his studies). In the nineteenth century, Lublin became a major center for Hasidism, centered around the tsadik Yaakov Yitshak, known as the Seer of Lublin and a disciple of the Great Maggid and Elimelech of Lyzhensk.

When was was declared in 1939, 45000 Jews lived in Lublin. They had seven synagogues, two mikva’ot, a hospital, a library, and schools. The ghetto was created in March 1941, and in March 1942, 30000 Jews were deported and exterminated in the Belzec camp, while the rest were executed on the spot or taken to the camp in Maidanek.

The Jewish city

First, absorb the atmosphere and take the pulse of this neighborhood with its rynek, its city gates, Grodzka Street, Po Farzu Square, and the old Jewish gate. To the right, heading down Grodzka Street, was located the Jewish community’s retirement home (dom starców), marked by a commemorative plaque.

The little streets running off Grodzka Street are the former Jewish alleys, often still neglected, which lead to Lubartowska Street and Ofiar getta (Victims of the Ghetto) Square, with a monument in memory of the murdered Jews of Lublin. The synagogue was located at 10 Lubartowska Street, transformed today into “An isba (room) to the memory of Lublin’s Jews”: a small museum with photographs and historical documents on display. At number 83 of the same street once stood the rabbinical school, Yeshivat Khachmei Lublin, today part of the Academy of Medicine, and, next door, the Jewish hospital. In 2004, these buildings were handed back to the Jewish community and today house a synagogue, mikvah and the Jewish community.

The two Jewish cemeteries are worth visiting, especially that on Kalinowszczyna Street, built in the sixteenth century. A number of personalities are buried here: Rabbi Shalom Shakna, founder of the Talmudic school, who died in 1558; Talmud scholar Yehuda Leybush ben Meir Ashkenasi, who died in 1597; Rabbi Itzhak Aizyk Segal, who died in 1735; and above all, the tsadik Yaakov Yitshak, who died in 1815 and whose grave is covered with small stones of homage. The other cemetery, the one on Walecznych Street, dates from the nineteenth century. It is large and contains beautiful graves as well.

The Maidanek camp

You cannot leave Lublin without stopping at the Maidanek camp, which is located today in a suburb of the city. It is easily visible from the road facing Chelm. The activities of the camp could be easily seen or guessed at from the city. A careful tour of Maidanek, where the barbed wire, barracks, gaz chambers, and crematorium have all been preserved, is particularly moving and impressive, comparable to that of Auschwitz (with fewer tourists, however).

The last Polish city before the Ukrainian border and former Austrian Fortress that fell to the Russians in the first World War, Przemysl is also a city with a strong Jewish community dating going as far back as the twelfth century, perhaps even the eleventh century. Before the Second World War, 20000 Jews lived here, or 40% of the population. In September 1939, after several days of German occupation, Przemysl was handed over to the Soviet-occupied zone. The Russians deported or evacuated 7000 Jews to the interior of the Soviet Union. In June 1941, the Germans occupied the city, created a ghetto, and then deported its inhabitants -first to Belzec, then to Auschwitz.

The Jewish quarter stretched across the slopes of “Castle Mountain”, between the San River, the marketplace, and Jagiellonska Street. The oldest synagogue in Przemysl, built in 1579 and designed by an Italian architect, was located at the intersection of Zydowska and Jagielonska streets. Another stood on the banks of the San; a third, the new Scheinbach Synagogue on Slowackiego Street, today serves as a library.

The synagogue in Unii Brzeskiej (Union of Brest) Square was built in the eighteenth century and reconstructed in 1963. Near the fortress, a monument commemorates the spot where the Jews of Przemysl’s “little ghetto” were executed.

In the cemetery on Slowackiego Street, a plaque has been mounted in remembrance of the mass executions that occured from 1941 to 1945.

Lancut is a small, pleasant city known for its Renaissance castle once belonging to the Lubomirskis.

The town also possesses a Baroque synagogue, one of the most beautiful in Poland. Built in 1761, destroyed during the war, and rebuilt during the 1960s, it has long served as a regional museum. In the 1980s and 1990s, it was completely restored once more, including the magnificent interior decor, the bimah, and the aron kodesh, where the Ark of the Law is kept. It houses today the Jewish Museum.

On Traugutta Street, at the site of the former cemetery, a plaque commemorates the execution of hundreds of Jews during the German occupation.

Jews settled in Rymanów so long ago that there exists no document mentioning their arrival. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the inhabitants of the city lived mainly from the cultivation of the vines and the wine trade, activity in which the Jewish community held a preponderant place. In 1765, a thousand Jews lived in Rymanów, or 43% of the population.

In the eighteenth century, Rymanów became a center for Hasidism in western Galicia, under the influence of the tsadik Menahem Mendel (also known as Mendel of Rymanów), who was a student of Elimelech of Lyzhensk and Shmelke Horowitz of Nikolsburg (Mikulov).

In the nineteenth century, the Jews of Rymanów worked mainly in trading and lending. The discovery of hot springs turned the city into a famous place for thermal tourism. The Jewish community benefited from this growth.

The Germans entered the city in September 1939. From 1940, Jews from nearby cities (including Krakow) were deported to Rymanów, the Jewish population consequently reached 3000 souls. The Rymanów ghetto was officially established in 1941. In 1942, the Jewish population was either deported to the death camps of Plaznow or Belzec, or shot on the spot. About 300 Jews

from Rymanów survived the war, 20 of them survivors of the camps, the rest had fled to the Soviet Union, or were hidden by local residents.

The synagogue was built before 1712, without its exact date of erection being known. Located near the rynek, on Piekna Street at the intersection with Kilinskiego Street, it attests, by its architectural importance, to the status the Jewish community once held in the city. Built of stone and brick, it integrated into the defense system of the city. The building was rebuilt in the 19th century. A women’s gallery, destroyed in the 1950s, was added. The synagogue was restored in 2005.

The Jewish cemetery of Rymanów is in excellent condition thanks to the work of maintenance and conservation pursued by local inhabitants. Located on Slowackiego street, it is better to call before visiting. In 2007, a grave dating back to 1615 was found, the oldest discovery to date. During the Second World War, it was the place where Jews were shot.

The legacy of Rabbi Elimelech

“Before he died Rabbi Elimelech laid his hands on the heads of his four favorite disciples and divided what he owned among them. To the Seer of Lublin he gave his eyes’ power to see; to Abraham Yehoshua, his lips’ power to pronounce judgement; to Israel of Koznitz, his heart’s power to pray; but to Mendel he gave his spirit’s power to guide.”

Martin Buber, Tales of the Hasidim: The Later Masters, Trans. Olga Marx (New York: Schocken Books, 1948).

The small city of Lesko possesses one of the most beautiful fortified synagogues in the region, built in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, with a turret that gives it the look of a little castle. Destroyed during the war, it was rebuilt in 1980; the interior mannerist decor had been redone, as well as the eighteenth-century iron gate and aron kodesh.

The Lesko cemetery is almost across the street from the synagogue. It dates from the seventeenth century, is very large, and contains many old graves with beautiful decorative motifs.

Jews began to settle in Rzeszów in the fifteenth century and, in the seventeenth century, built two synagogues, both of which remain, almost side by side. They are fairly easy to find, located right in the city center.

The Stara (Old) Synagogue, dating from the first years of the seventeenth century, today houses the city archives. It is rather small, but well restored on the outside. A Star of David can still be seen on one of the walls.

The Duza (Large) Synagogue is from 1686, It is more imposing, with large bearing walls reinforced by pillars that give it the look of a fortress. rebuilt in the 1960s, today it houses an art gallery office in the main room and an upstairs café in the galleries for women. A visit to the site offers a glimpse of what the interior looked like before the war, when 14000 Jews lived in Rzeszów. They were all deported to Belzec or Auschwitz.

On Rejtan Street, a large Jewish cemetery remains, its many graves damaged, however, with overturned tombstones, and sometimes overgrown with vegetation.

Over time and suffering from territorial conflicts between the great powers of the region, the Jews managed however to participate in the active life of Rzeszow. Mainly in trade, their property rights being limited to housing. Many shops opened in the city center. So much so that at the end of the 18th century Rzeszow was nicknamed “the Jerusalem of Galicia” by the academic Bredetzki.

Jews were registered in a special state register with surnames often indicating their origin like Krakowski, or names related to trades like Tabachnik.

Thanks to a movement of emancipation and egalitarianism in 1848, the Jews finally obtained the same rights and also participated in the political life of the city. Confirmation of this development was not made until about fifty years later, with some leaders returning from time to time to progress.

In 1860, the Jews were thus able to buy land for their new cemetery, fields and other land. Before that, they had developed the clothing and jewelry industries. They met in this area a certain regional success, their jewelry even selling in places as distant as Livorno or Alexandria.

The democratization of access to the trades enabled many Jews to embark on agriculture and town planning, exporting eggs or modernizing the city’s drainage systems.

The Jewish population grew from 3,375 in 1800 to more than 8,000 in 1910 (which represented more than a third of the total population).

The Haskalah movement was a great success in Rzeszow. Famous scholars include Abba Apfelbaum, journalist and author of biographies on Italian Judaism, as well as Moshe David Geschwind, journalist, translator of Hebrew and Yiddish and secretary of the community for 30 years. Another journalist, Leon Weisenfeld, who published in Polish newspapers, who created the newspaper “Yiddishe Volkszeitung” and was the author of three novels.

Also known on the national scene, Doctor Wilhelm Turteltaub, an expert on German literature. While continuing his medical studies, he wrote famous plays which were performed in Germany.

Chassidism also gained momentum, thanks to the pupils of Rabbi Elimelech of Lizhensk, hence the construction of a second synagogue in the 19th century. His book “Noam Elimelech” influenced the development of the movement throughout the region of Galicia.

A hospital, a retirement home and cultural institutions were created at this time.

As early as 1934, supporters of the Nazi regime, which did not invade Poland until five years later, began to vocalize a certain anti-Semitism. At the start of World War II, the Jewish population was close to 15,000, an increase caused by the resettlement of Jews by the German army. The occupants build a ghetto there of more than 20,000 people.

During the invasion, German troops did not immediately adopt a hostile attitude. They waited for the celebrations of Rosh Hashanah and Kippur 1939 to identify the Jews leaving the synagogues and forced them to dive into the deep waters of the Wislok River. Many very harsh measures were put in place with regard to the Jews. Forced labor, destroyed synagogues, famine, summary executions …

The vast majority of Rzeszow’s Jews were deported or killed in the woods. Only a few hundred survived the Holocaust.

The small community reconstituted after the war of 300 people erected a monument in memory of the victims.

The scale of the massacres in Rzeszow motivated many Jews who had been fortunate enough to flee before the Holocaust and their descendants to carry out genealogical research in order to find relatives, or more often the names of relatives killed. The generation of survivors sometimes preferring not to turn around and discuss the atrocities in order to be able to rebuild themselves, their descendants are very involved in this research.

We met with genealogy expert Philip Trauring, whose ancestors came from Rzeszow. He has created several acclaimed sites and is involved in numerous projects for the conservation of Jewish heritage.

Jguideeurope: What motivated you to create the Jewish genealogy website of reference B&F: Jewish Genealogy and More?

Philip Trauring: B&F: Jewish Genealogy and More started out as a simple blog where I could share knowledge about Jewish genealogy. I had been researching my own family for a number of years, and had begun to volunteer with a local genealogy society, but felt a web site offered me the easiest way to help the most people. In 2016, after realizing I was looking up the same things over and over again when helping people, I decided to create an index of resources online. I added the B&F Compendium of Jewish Genealogy with Jewish genealogy resources for over 200 countries and territories, as well as 1400 towns in Poland. It was a major undertaking, and involves a lot of work to keep up-to-date. However, now when people ask me for help researching where their family came from, I can just send them the relevant links. Importantly, the site also allows users to leave comments on the resources to help others that might use them in the future.

Concerning Poland, you offer more than 20000 resources. How do you explain such availability? Is it a recent phenomenon?

Part of the reason I chose Poland to expand to town-level resources was that I felt I could find enough resources that covered many towns within Poland. It wouldn’t work if I added over a thousand towns, but most only had one or two resources. My goal was to average ten resources per town. I looked for sites that had extensive resources on towns, and made sure I had a certain number of sites that all had resources for hundreds of towns.

I then built my list of towns, which now totals over 1400 where Jews had lived in Poland. Building just the list of towns was difficult, as just because a town was mentioned in a record didn’t mean I could confirm its location. Many towns in Poland have the same names, many names changed over time, and many villages became neighborhoods of larger towns and cities. Spending the time confirming the towns however has allowed me to have a very accurate list of towns that form the basis of the Polish resources.

What discovery in Rzeszow surprised you the most?

Most of my father’s extended family lived at some point in Rzeszów. Both of his parents lived there as children, and both had family members going back many generations there. Rzeszów, or Reisha as the Jewish community called it, held an important place among Jews in Galicia. I did some research into the centrality of Rzeszów by looking through marriage records in the Rzeszów archives, and seeing what other towns spouses came from. Marriage records included records from the towns the spouses came from, frequently including their birth records. Each community had an official stamp, and the rabbis of those communities also had an official stamp, and I collected many of those stamps in an article which shows the towns connected to Rzeszów through these records.

What current projects are being undertaken to restore Rzeszow’s heritage?

There is an annual memorial in Rzeszów, which has been going on for 12 years. You can see a video of the most recent one on YouTube It takes place in one of the Jewish cemeteries which today sits right next to the university. There is a Facebook group called In Memory of Jewish Rzeszów which has people who are working on a project to restore that cemetery and make it a place of remembrance instead of just a walled off mostly empty piece of land.

Your work on the town of Kańczuga was also widely shared. Is there also a personal connection?

My gg-grandfather lived in Rzeszów, but was actually born in Kańczuga, a small town not far away. Over the years I’ve tried various ways to stay in touch with other Kańczuga descendants, including a mailing list, a Facebook page, and at the center of it the Kanczuga.org web site where I post updates on research. While Rzeszów was the largest city in the region, Kańczuga served as a center among smaller villages in its area (I list about 20 of those villages on my Neary Villages page) and I try to include those villages in my research since they overlap so much with Kańczuga. Through this group of descendants we’ve funded research in local archives and helped restore the Jewish cemetery. Recently, a non-Jewish native of Kańczuga, Patryk Czerwony, who moved to the US as a child, has been helping organize projects to memorialize the Jewish community and we’ve worked with him to get some of these projects done.

In Tarnów, half of the population was Jewish: between 20000 and 25000 people worked principally in the clothing and hat industries (sixty or so businesses), arts and crafts, and trade. Some were rich merchants, lawyers, and doctors who owned beautiful houses still dominating Walowa Street. The others, poorer, were concentrated mostly in the populated districts around Zydowska, Warynskiego, Lwowska, and Szpitalna streets. Renowned intellectuals were born or lived in Tarnów, including Warsaw Ghetto eulogist Adolf Rudnicki (1912-90).

The most important remnant, but also the most “trivial” of earlier Jewish life, is the bimah from the old synagogue on Zydowska Street: the synagogue itself was razed, leaving only a patch of green, in the center of which sits the former stone bimah, reminiscent of a fountain.

Behind the bimah, take Rybna Street to see the former Jewish houses with courtyards crisscrossed by upstairs galleries. Beyond Walowa Street, on Goldhammer Street, stood the Jewish community’s prayer house, where services have not taken place since 1980 for lack of a minyan. A bit further on, in what used to be the ghetto, lie Wiezniów Oswiecima (Prisoners of Auschwitz) and Bohaterów Getta (Heroes of the Ghetto) square, where a monument stands to the victims of the Shoah, not far from the old mikvah, today a spa.

Nowodabrowska Street leads to the Jewish cemetery on Sloneczna Street. The cemetery dates to 1583 and is one of the oldest in the region. It remains active, though devastated: the most luxurious gravestones have been destroyed or stolen. At the entrance stands a columns that came from the Nowa (New) Synagogue commemorating the massacre of 25000 Jews of Tarnów, on the spot where the first mass executions took place on 11 June 1942.

In 1335, King Casimir the Great founded an independent city near Kraków, Kazimierz, in which he permitted Jews to settle around Sukiernikow (Clothier) Street (now called Jozefa Street), next to the Christian quarter.

They built the Stara Synagogue, a mikvah, hotel, and wedding chapel on the main street called Szeroka (Wide) Street. In the sixteenth century, a large number of Jews arrived here from Bohemia. In 1553, Jews bought the land located between Waska (Narrow) Street and the city wall to construct houses, as well as a plot on Jakuba Street for the “Rema” cemetery and synagogue. At the time, three gates provided access to the Jewish quarter: one near the city wall and the Stara Synagogue, a second near the cemetery, and a third on Jozefa Street, between the Christian and Jewish areas. The Wysoka (High) Synagogue was later built near the third gate.

In 1564, the Jews obtained from King Sigismund August the privilege of non tolerandis christianis: the Christians were forbidden from buying plots of land of these streets and, conversely, Christian owners could not sell plot to anyone other than Jews. In 1635, all the land located of these few streets in Kazimierz was owned by Jews.

In the seventeenth century, the growth of the Jewish community required the building of a new synagogue: the Popper Synagogue on Szeroka Street, founded in 1920 by a rich merchant, Wolf Bocian; the Ajzyk Synagogue, named after Isaac Jakubowicz in 1644; and the Kupa Synagogue. At the time, Kazimierz was one of the largest Jewish cities in Europe, with 4500 residents, as compared to the 5000 in the city’s Christian section. As in Kraków, the wealthier Jews of Kazimierz had architects design new stone houses, and reconstruct the Stara Synagogue, destroyed by a fire in 1557.

After Poland was divided, Kraków and Galicia were annexed by Austria. In 1800, the Austrian government reunited Kazimierz and Kraków.

In 1867, the Austro-Hungarian constitution pit an end to discrimination against Jews and even allowed them to freely choose their place of residence. The poorest and most religious Jewish remained in Kazimierz at the edges of the former ghetto. The more assimilated built a Reform synagogue, the Temple, on Miodowa Street, beyond these limits.

During the occupation, the Kraków ghetto suffered the same fate as the other Polish ghettos. It was liquidated in 1943, its inhabitants exterminated in Belzec or in the Plaszow camp. The Jewish quarter of Kraków, Kazimierz, is the best preserved of all in Poland, with considerable cultural value for tourists. Long neglected and repressed in Polish consciousness after the disappearance of its residents, it has reemerged as a valuable piece of Jewish heritage thanks to Steven Spielberg’s filming of Schlinder’s List here. Since 1991, moreover, the city has ben putting on an annual Jewish cultural festival here, normally from June to July. To prepare your visit of Jewish Kraków, contact the Jewish community of the city.

Last year, the European Days of Jewish Culture had a larger meaning in Krakow. The Jewish Community Center has always been very involved but with the war wages by Russia in Ukraine its role has evolved. Here’s our interview with Agnieszka Kocur-Smoleń, Director of Programming at the JCC of Krakow.

Jguideeurope : Can you tell us how the Jewish museum was created?

Agnieszka Kocur-Smoleń: The JCC was opened in 2008, during an official ceremony, by the Prince of Wales. The center provides social and educational services to the Jewish community of Krakow. But it has also different purposes. First to participate in the resurgence of Jewish life in Krakow and foster Polish-Jewish relations. For such purposes, it was also important to provide a symbolic location, in the heart of the city’s historic Jewish quarter, Kazimierz.

Are there educational projects proposed by the museum and how is the city of Krakow participating in the sharing of Jewish culture?

We have a whole variety of educational projects, activities, events for the community as well as for people who would like to deepen their knowledge and understanding of the Jewish world. We work with the local school, cooperate with universities, other non-profit organizations, museums, cultural centers. All of this in order to share Jewish culture broadly.

Are you participating in this year’s European Days of Jewish Culture ? If so, what was organized at the museum ?

Each year we participate in the Jewish Culture Festival as the partner organization and we prepare the rich program of accompanying events. The Festival is supported by the city of Krakow. We have created a program of 38 events during the festival lasting 7 days – lectures, talks, city games, culinary show, sightseeing, dance workshops, genealogical consultations, debates, activities for kids and seniors, yiddish classes, Shabbat dinner, etc.

You have been involved in helping Ukranian refugees. Can you give us some details ?

The JCC and its partners have helped over 80 000 Ukranians in the first four months of the Russian attack, and continue doing so. Both refugees who have fled to Poland and Ukrainians on the other side of the border, not differentiating between the cultural and cultual affiliations. The JCC serves as a distribution point for food, medecine, toys, clothes… Over 12000 hotel nights have been provided. Summer camps are also organized for Ukrainian kids. A hotline has been set up to answer all types of questions and problems, and also a team of 12 psychologists. We have also partnered with a local university and an Israeli NGO to train 68 more psychologists to deal with such a crisis. And many more actions to diminish the suffering of the civil population.

Kazimierz

The tour begins on Miodowa (Honey) Street, accessed from Szeroka Street, the ghetto’s main street. At the intersection of these two street. At the intersection of these two streets stands the beautiful building that housed the old mikvah, dating to 1567, converted today into a restaurant where Jewish specialties are served.

Szeroka Street is, in fact, a large, rectangular square, around which extend the majority of Jewish community buildings, houses, and Jewish restaurants, with the cemetery and the Rema Synagogue on the right, the Stara Synagogue straight ahead, and the Popper Synagogue on the left. At the center of the square a little park is surrounded by an enclosure featuring seven-branch candelabras. The rest of the square is now a parking lot.

The songs of Mordecai Gebirtig

Mordecai Gebirtig, born in Kazimierz in 1877, was the most talented of the Yiddish singer-author-composers of the twentieth century. He was a carpenter in the Kraków ghetto, where he was murdered in 1942. His nostalgic songs, like “Kinderyorn” (Childhood Years), still sounds in our ears. In 1938, he composed a premonitory song, “Unzer Stetl Brent” (Our Shtetl is Burning), which was to become a hymn for ghetto combatants: “It is burning, little brother it is burning ! / Oh, our poor shtetl is burning”.

The Ancient Synagogue was built in Gothic style during the fifteenth century and inspired by synagogues in Worms, Prague, and Ratisbon. It was reconstructed in Renaissance style following a design by the Florentine Matteo Gucci after a fire in 1557. Today it houses the Kraków Jewish History and Culture Museum. Not far from it, you can find the Museum of Galicia which gives tribute to the Jewish cultural heritage of the region. It was created thanks to the initiative of a British photograph and inaugurated in 2004. Exhibits about Jewish life are shown there.

The magnificent interior perfectly recreates the atmosphere of an old synagogue, especially with the circular wrought iron bimah in the center, a sort of temple within a temple. To the sides and in the rooms adjacent to the prayer area, works of art and religious objects are on display, as well as photographs depicting old Kazimierz.

Founded in 1620, the old Popper Synagogue is located behind the courtyard. It was destroyed during the war, the reconstructed, and finally converted into an art center for children and adolescent. At the entrance to the synagogue courtyard are located the Ariel café-gallery and a Jewish restaurant-café.

The Landau House dates back to the fourteenth century, one of the oldest and largest stone houses of the former ghetto. Its architecture is distinctive and immediately attracts attention. Inside, there is a café and the Jarden Jewish bookstore, which offers guidebooks to Kazimierz and organizes guided tours of locations filmed for Schlinder’s List.

The Rema Synagogue was founded in 1553 by Israel ben Josef Isserles, who hailed from Ratisbon. It bore the name of his son, philosopher and famous rabbi Moses Isserles (1525-72), also known as Reb Moses or Rema. Its monumental front door is also that of the cemetery! With the latter, this synagogue in fact forms an important fifteenth-century Jewish architectural ensemble, comparable to the Altneuschul and cemetery in Prague. Inside, it is relatively small. It, too, possesses an interesting wrought iron bimah. Besides the one in Lublin, this is the oldest Jewish cemetery in Poland, and worth a careful visit. Here one finds numerous graves of personalities famous in their time, notably those of Moses Isserles and his family, but also Eliezer Achkenazi, a rabbi in Cairo and later Poznan; rabbi and Kabalist Nathan Spira; and Yomtov Lipman Heller, a rabbi in Vienna, Prague, Nemirov, and finally yeshiva director in Kraków. The grave of Moses Isserles, just behind the synagogue, is one of the most remarkable: it is covered with small stones that visitors leave as a sign of tribute. A bit further on, the cemetery rises up, forming a hill, which is, in reality, an accumulation of tombs. The cemetery wall, near the entrance, is made up of concrete gravestones.

Taking Szeroka Street to its end, you will reach Jozefa Street, where, at number 38, across from a small square at the intersection with Waska Street, stands Wysoka (High) Synagogue, its name owing to the second-floor location of its prayer room. Built between 1556 and 1563, it was destroyed by the Germans, rebuilt after the war, and donated as a historical monument. Despite, its beautiful exterior, nothing much remains inside.

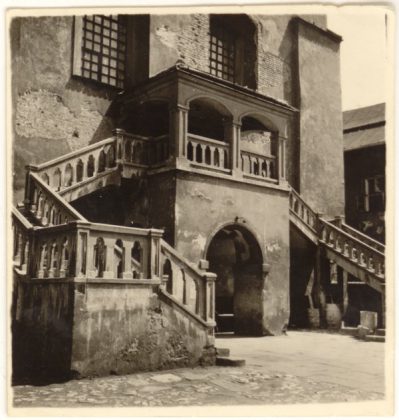

From Jakuba Street can be seen the back side of the impressive Ajzyk Synagogue, at the intersection with Izaaka Street facing the cemetery wall. Founded by rich merchant Isaac Jakubowicz (also known as Reb Ajzyk ben Jekeles), it dates to 1638. Its facade and monumental staircase face Kupa Street. Destroyed by the Germans but now rebuilt, it is a place of memory featuring an exhibit about Polish Jews. Films about Kazimierz are also shown here.

The Kupa Synagogue is located on Warzauer Street at the end of Kupa Street. Built in the early seventeenth century at the site of the ghetto’s outside wall, it is recently restored. It contains beautiful paintings depicting the cities of Palestine. Further on is the very picturesque New Square (Nowy Targ), also called Jewish Square, where a circular covered market, or okraglak, has been set up and where ritual slaughter was at one time performed.

The Talmud Torah school used to be at 6 Estery Street.

Continuig on to Meiselsa Street, the magnificent interior courtyard of ber 15, featuring galleries running through the second floor and a porch overlooking Jozefa Street. In the background looms the bell tower of the Church of Corpus Christi. A courtyard entered at Jozefa 12 Street was the location of a scene from Schlinder’s List.

From Bozego Ciala Street, Miodowa Street leads to the Reform Templ Synagogue (at the intersection with Podbzezi Street), which is remarkable for its beautiful stained-glass windows.

Behind the railroad tracks on the other side of Miodowa Street is the new Jewish cemetery. It was built in 1800 after the Rema cemetery was closed. Its extensiveness recalls the large Jewish community that was here before the war. At the entrance, a monument assembled from numerous gravestones and commemorative plaques has been put up in memory of the victims of the Shoah.

By taking Starowisla Street, on the other side of the Vistula, you will reach what used to be the ghetto during the German occupation, around Bohaterow Getta (Heroes of the Ghetto) Square and Lwowska, Josefinska, and Limanowskiego streets. A museum is located in the Pod Orlem pharmacy, whose owner, Tadeusz Pankiewicz, greatly helped the Jews of the ghetto. On Lwowska Street a fragment of the ghetto wall can be observed, resembling an alleyway of gravestones.

Further on, in Plaszow (on Kamienskiego Street), a monument stands in honor of the victims deported from the Kraków ghetto to the concentration camp built on this very spot.

Auschwitz (Oswiecim)

Auschwitz remains the most horrible symbol of the Shoah, a symbol periodically threatened either by denial or by revisionism. In the Communist era, each country was permitted to construct refugee camps, but nowhere was it written that almost all the deportees had to be Jewish of Gypsy. All were presumed to be potential Communist Resistance fighters. Today, a large cross sows greater confusion, attempting posthumously to Christianize the victims.

A tour is required for anyone who might still doubt the reality of the Final Solution or imagine that is was merely a “detail” of the Second World War. More than 800000, perhaps over 1 million, victims died in Auschwitz. The tour comprises two camps: the main camp of Auschwitz (Oswiecim) and the one in Birkenau (Brzezinka), where the gas chambers were located. Although the tour is trying and exhausting, it is essential to see both camps. It is advised to see Auschwitz during the day, using Kraków as a base, rather than having to spend the night in a place of such absolute horror. Expect the tour to take four to five hours.

From Bialystok, a detour toward Tykocin is imperative: it has effectively preserved the structure and architecture of an old shtetl. This town, tiny today, was in times past more important than Bialystok, with a larger and older Jewish community. The community dates back to 1522 and was, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, one of the most prominent in Poland. Like Bialystok, in September 1939 Tykocin fell under the Soviet-occupied zone connected to Belarus. In August 1941, the Germans executed 1400 Jews here and sent the rest to the Bialystok ghetto, where 50000 of their fellows were confined. In November 1942, Mordechai Tenenbaum of Warsaw began to organize a resistance, but the ghetto was liquidated beginning in February 1943 and the armed uprising crushed. All of the ghetto’s inhabitants were exterminated in Treblinka and Maidanek.

The magnificent synagogue here, built in 1542, is still remarkable with its very tall, late-Renaissance frame and Baroque roof. It

has been restored and transformed into a Museum of Judaism. The interior is splendid, with a large bimah, frescoes depicting exotic animals, inscriptions with beautiful Hebrew lettering, and stuccowork.

In front of the museum, at 4 Kozia Street, the Tejsza restaurant offers Jewish cuisine. Behind the museum, old Jewish houses still stands on Kozia, Kaczowska, and Pilsudskiego streets.

From Treblinka, rather than return to Warsaw in the evening, you can travel on to Bialystok, near Belarus, a city with a Jewish tradition so strong that in 1913, Jews numbered 61500, or 70% of the population.

Of the one hundred synagogues and houses of prayer -the three main ones being the Groyse Shul on Szkolna Street, the Chorszul (Choral Street) on Zydowska Street, and the Pulkowa Synagogue -there remains almost nothing left to see, except for the nineteenth century synagogue at 3 Piekna Street, today the House of Youth and Culture.

Located on the bank of the Ner, a tributary of the Warta in the region the Germans called Wartheland, Chelmno is where “gas trucks” were tested beginning 1941, an early form of what later became the gas chambers. Jews were assembled in the Catholic church and from there sealed in trucks, with the exhaust pipe turned inward. The number of miles between the village and forest and the truck’s speed were calculated in such a way that upon arrival, the Jews would have died from asphyxiation; the needed only to be buried in previously dug graves. A large part of the Lodz ghetto was exterminated in this way in Chelmno.

It is in Chelmno that Claude Lanzmann begins his film Shoah. An man is seen, a rare Shoah survivor named Simon Srebnik, as he returns to places where, as an adolescent, he sang for the Germans while they conducted their sorrowful work. He sang so well, in fact, that his life was spared, and the Polish peasants of the region could all remember him.

Chelmno’s church still stands, towering over prairies where animals graze along the Ner. One almost expects seeing that rare survivor sailing in his small boat, as depicting in Lanzmann’s film. At the church’s entrance, a plaque recalls the fate of the region’s Jews.

A mile or two from here, in the forest, is the camp, the extermination site where large, rectangular mass graves were dug to bury the cargo from the gas trucks. A monument has been erected here: a path leads through the various grave sites, lined with stelae evoking what happened and recalling the names of the shtetlach that vanished here.

Arriving in Treblinka by train recalls the horror of the Warsaw Ghetto inhabitants’ final trip from the Umschlagplatz to the gaz chambers. To reach Treblinka from Malkinia, the railway line follows hairpin switches: the train must therefore stop and travel in reverse, with the locomotive pushing the cars toward the camp, as explained by railroad worker Henryk Galkowski in Shoah, a train conductor who made the trip three times a week over an eighteen months period.

The railroad line crosses the Bug, then a rather thick pine and conifer forest. At the Treblinka station, an unusued and rusted freight train still sits, as if parked there since its final trip. The site of the camp is located almost immediately past the station, at the end of a short path leading into the forest toward a concrete ramp designed to resemble railroad ties. Nothing remains of the camp but information panels in several languages, as the Germans destroyed it all to cover up their crime.

At the very end sits a large, circular space covered with tombstones, each symbolizing a shtetl, small Polish town scoured of its Jews. The stones bear the place names of hundreds of towns from the Warsaw, Bialystok, Vilnius, Minsk, and Mazowiecki regions, among others. There is a stone dedicated to “Janusz Korczak and his children”. In the center, a stone-branch candelabra. The site is extremely still and encourages reflection.

Lodz is a large Polish industrial city where a significant Jewish working class, along with merchants and rich industrialists, were concentrated in the nineteenth century. A fine representation of the reality of life in nineteenth-century Lodz can be seen in Andrezej Wajda’s 1974 film Ziemia Obiecana (Promised Land).

Under the occupation, the Lodz ghetto (with more than 150000 people) was, just like the one in Warsaw, a concentration camp in the middle of a city, where the Germans deported Jews from other towns in Poland and Germany (the Germans had renamed the city Litzmannstadt). The Judenrat was headed by Chaïm Rumkowski, an authoritarian man and controversial figure to the Jewish community. Rumkowski’s polices allowed him to survive a year longer that did Jews in the other cities. Although the first deportations to the Chelmno camp began in 1942, it was not until August 1944, only just before the liberation, that the remaining Jews of Lodz (76700 people) were deported and exterminated in Auschwitz. Only 800 Jews here managed to survive until the end of the war, and almost none remain today. When visiting Lodz, contact the very active Jewish community of the city.

Lodz main street, Piotrkowska, forms the link between the city center and the Jewish quarter, located in the northern near Rewolucji Street 1905. The synagogue still stands on this street in the courtyard of number 28 and is supposedly operational when a minyan is gathered. From the street, you can still see its beautiful facade and sign in Russian and Polish. In the courtyard, a smaller building features a stained-glass window and a Star of David.

On Piotrkowska Street near Zamenhofa Street, there was a Jewish community building dating back to 1899, serving first as a place of ritual slaughter and later as a synagogue. After the was, it was converted into a shop and then a printing house.

The enormous Jewish cemetery is truly impressive. Built in 1892 on ninety-nine acres, it features a beautiful, railed gate and around 180000 graves, including those of relatives of the poet Julian Tuwin and pianist Arthur Rubinstein.

The Museum of Lodz’s Traditions of Independence is currently the oldest historical museum in the city. It consists of three sections and the Roma forge (place of memory of the extermination of the Roma population during the Second World War).

The main headquarters of the museum is located in the premises of the prison built in the years 1883-85, on the order of the Tsar of Russia, which was mainly intended for political prisoners. During the German occupation and after the end of the Second World War, it was a place of isolation for women, imprisoned for political crimes.

Radogoszcz’s martyrology section is located in the former Samuel Abbe factory, which during the Second World War served as a police prison for residents who violated the law of the German occupation. Radogoszcz was a male transit prison. According to the 1944 data, prisoners spent periods of not more than two months awaiting trial or transfer to other prisons or camps. This is where the convoys for mass executions in the Lodz region started. It is also from here that had left the prisoners who were killed during the biggest public execution, in the town of Zgierz on March 20, 1942. It is estimated that during the German occupation nearly 40000 prisoners went through this establishment.

On the night of January 17 to 18, 1945, just before the arrival of the Red Army, the Nazis set the prison on fire while placing a machine gun in front of the only exit of the building. In the ensuing massacre, more than 1,500 people died. This place is dedicated to the memory of the victims of the Second World War and the martyrdom of the inhabitants of Lodz and the region of Warta.

During Hitler’s occupation, the section of the Radegast station bore the name of the transshipment station of the Radogoszcz ghetto (Verladebahnhof Getto-Radegast). It was the point of transshipment of food, fuel, raw materials for the ghetto population and its workshops, as well as the point of loading of the products that were made there. The station also became a “Umschlagplatz” for people deported to death camps. Today, it is a place of memory of the martyrdom of the Jews of Lodz and its surroundings, but also of the Jews of Vienna, Prague, Berlin, Berlin and Luxembourg. This is one of the most moving places in Lodz. The scenography, sober and majestic, makes the visitor evolve in a dark corridor, punctuated by the visual documentation of the daily life of the Jews of the Lodz ghetto. If you only have one day planned in Lodz, this memorial must be on your list.

The Marek Edelman Dialogue Center is a cultural and educational center that reflects the multicultural and multi-ethnic history of Lodz. The exhibitions and lectures are mainly focused on the history of the city’s Jews and relations between the Jewish and Polish communities. When leaving the Center, take half an hour to walk around the impressive Survivors Park, overlooked by a statue of Jan Karski.

To finish your visit of Lodz, go for dinner to the Manufaktura, quasi city in the city and former location of factories of Izrael Poznanski. This site, which never tires of astonishing, shows the influence of the Jewish industrialist on the city.

Izrael Kalmanowicz Poznansky

(Aleksandrów Lódski 1833 – Lódz 1900) was a Jewish-Polish businessman and entrepreneur living in Lódz.

His modest father settled in the old town of Lódz in 1834, holding a leather and textile stand. After finishing high school, Izrael Poznanski began his meteoric rise as a street vendor. Gradually, he became one of the most prominent entrepreneurs in Poland, forming an industrial empire that employed thousands of workers in its cotton factories.

He also gained a reputation as a philanthropic patron: at first not very concerned about the well-being and security of his staff, he undertook at the end of his life to engage in caricative actions and built orphanages, schools and schools. hospitals.

Together with Ludwig Geyer and Karol Scheibler, the two other “cotton kings”, Poznański became the most important manufacturer in Łódź, a city that was highly industrialized and multi-cultural at the time, mostly populated by Poles (Catholics and Jews) and Germans (Protestants) and whose bourgeois backgrounds were very well portrayed in Władysław Reymont’s novel entitled The Promised Land (Ziemia Obiecana), later adapted for film by Andrzej Wajda.

Poznański has left Łódź an important industrial heritage that constitutes a unique architectural ensemble, having survived the two world wars. The sites related to his memory are also among the most remarkable of the city: we can mention the huge industrial buildings of Ogrodowa Street, today completely renovated and which became a shopping center, services and entertainment called “Manufaktura”, the nearby Poznański Palace, now a museum (with an important exhibition on Arthur Rubinstein) and a marble tomb in the Jewish cemetery – the largest Jewish cemetery in Europe – whose style and stature define strongly with the Jewish tradition which forbids any form of ostentation for funerals and tombs and which is the largest individual Jewish burial monument in the world.

Eric Slabiak is, with his brother Olivier, the founder of the famous group Les Yeux Noirs (1992), mixing gypsy and Yiddish music. In 2019, after 8 albums and 1,800 concerts around the world, he created the band Josef Josef. On the album of Les Yeux Noirs, Balamouk we find the song “Lodz”, inspired by his family link to the city. Here’s our interview with the artist.

Jguideeurope: What is your family link to Lodz?

Eric Slabiak: This is the birthplace of my maternal grandfather. Whenever I hear the name of this city, I have the impression that the entire Jewish history of Poland has been unfolding there. When I talk to people whose ancestors were also from Lodz, I see their eyes light up. A look immediately charged with a certain twist of melancholy.

It is a city that I perceived in my imagination as a shtetl, a village. A feeling reinforced by the fact that my family was of modest means. Later, I learned that this is actually a big industrial city.

My family comes from many Polish cities: Warsaw, Lublin, Czestochowa, Lodz and others. Lodz represents for me the mysterious city, it arouses my curiosity. Nourished by a double feeling of affection and rejection. My ancestors were driven out. Nevertheless, there remains a bond that transcends generations. I can’t quite explain it to myself but it is there.

What inspired the song “Lodz”?

Today I want to explore Lodz and other Polish cities. I would like to feel there, even if they are fantasized connections, what my family went through. Find the neighborhoods in which they lived, the traces of their ancient presence of several generations. A nostalgia for a past that I have never known in a place that I have not known. For my grandparents, it was inconceivable to return there after being driven out for fear of being welcomed by the Poles. So, through this piece, I tried to translate my impressions, my imaginary memories of Lodz.

Did you also evoke family roots in other parts of your work?

I come from a family of musicians, so the wide range of emotions was very present around the songs, music and dance. My passion is absolutely linked to my family. The one that I didn’t know and the one that I knew. So it was found in different ways on the Yeux Noirs albums and on Josef Josef’s. I often choose Yiddish songs thinking that my grandparents heard or sang them themselves. On Josef Josef’s album there are five Yiddish songs. On stage, I often add others …

Jew began settling in Góra Kalwaria (Calvary Mountain) in 1795, and by a century later they had attained more than 50% of the city’s population. The Tsadik Isaac Meir Rothenberg Alter, brother-in-law to Menahem Mendl of Kotzek, settled here in 1859. The Jews called Góra Kalwaria “Gur”, or the “New Jerusalem”, so well-known were the tsadik Alter and his dynasty. During the occupation, all the Jews of Góra Kalwaria were transferred to the Warsaw Ghetto, and from there to Treblinka.

Albert Londres’s account

Albert Londres visited Albert Londres in 1929: “Two thousand inhabitants, but one of the navels of eastern Jewry. Here, the famous zadick [sic] Alter, successor to Baal Shem Tov, the one who took the Zohar across the Carpathian Mountains in a car, sought contact with God, just like our fans of wireless radio seek the airwaves.”

Albert Londres, Le Juifs Errant est Arrivé (The Wandering Jew Has Arrived). (Paris: Le Serpent à Plumes, 2000).

Today, the edifices of two synagogues remain, at Pijarska Street 5 and 10-12, converted today into the stores. The Jewish cemetery dates to 1826 and often receives visitors from the United States.

Warsaw: the name alone evokes the martyrdom of the ghetto following the April 1943 insurrection. Events here shall remain firmly fixed in the conscience of humanity.