Wolfgang Tillmans: Fold Me

Wolfgang Tillmans, Rain Splashed Painted Life, 2022 Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/Hong Kong; Galerie Buccholz, Berlin/Cologne; and Maureen Paley, London

Written by: Michael Galati

Wolfgang Tillmans is constantly trying to look at the objects, practices, and ideas we take for granted in new, transformative ways. In his preeminent 2022 exhibition To look without fear, Tillmans amplified the role that the panoply of different lives play in creating society and invited us to question how we see ourselves in such a mix. Now, in a new exhibition at the David Swirner gallery in New York, Tillmans tackles a larger assignment. In Fold Me, Tillmans wants to question if it’s possible to reconceive of a new way of thinking about the world’s order.

Tillmans does so by first establishing Gottfried Leibniz’s 1714 text, Monadology, as his referent. Monadology lays out Leibniz’s metaphysics of the world in which monads, or simple, indivisible substances that act in a predetermined way, make up the fundamental building blocks of the objects we see in the world. This conception of the world takes existence and interactions between objects as participating in a preordained harmony. All is determined.

Modernity took issue with this way of seeing the world, and in 1988 Gilles Deleuze published a critique of Leibniz’s monad. For Deleuze, monads are just folds of space and time, places where they overlap and warp the fabric of existence. He figured them as “not something other than the outside, but precisely the inside of the outside,” or, in classic post-structuralist fashion, they are precisely the breaking down of boundaries and forms. Deleuze sought to unravel Leibniz’s pre-ordained view of the world to allow for dissonance and ostensible incompatibilities to exist at the same time. Thus, Deleuze’s interpretation of the monad, is one in which a fold collapses the inside/outside opposition. In his definition, the inside is always contained in the outside, which creates a causal inside/outside chain ad infinitum.

What Tillmans does in Fold Me, in a way, is examine where Deleuze’s interpretation of the organization of the world appears to be true. Tillmans is interested in where chance and order meet, where ways of seeing and viewing are interrupted by the image and where space itself can be reimagined. The way to do that, for Tillmans, is to look at where patterns break, where what we expect to happen does not.

Wolfgang Tillmans, Sweat It Out Ceiling, 2022 Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/Hong Kong; Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne; and Maureen Paley, London

For example, two images take folds in the Earth’s surface as their subject, but each presents a vastly different take on folding that is strong enough to question a fold’s ontology. Lunar Landscape (2022) is a 107” x 140” portrait of the reflection of moonlight on an all-encompassing expanse of the ocean. The moonlight glitters off the slightest of ripples on the surface of the water, while the horizon in the background interjects an infinite void. Without the wave crashing on the shore in the foreground, the ocean would be indistinguishable from the surface of the moon. The immensity of this image propounds the gravity of both the ocean and space as immovable realities whose existences supercede the inside/outside division. We take them as they are, and the folds here function as fluid, malleable, constantly changing features of being and existence.

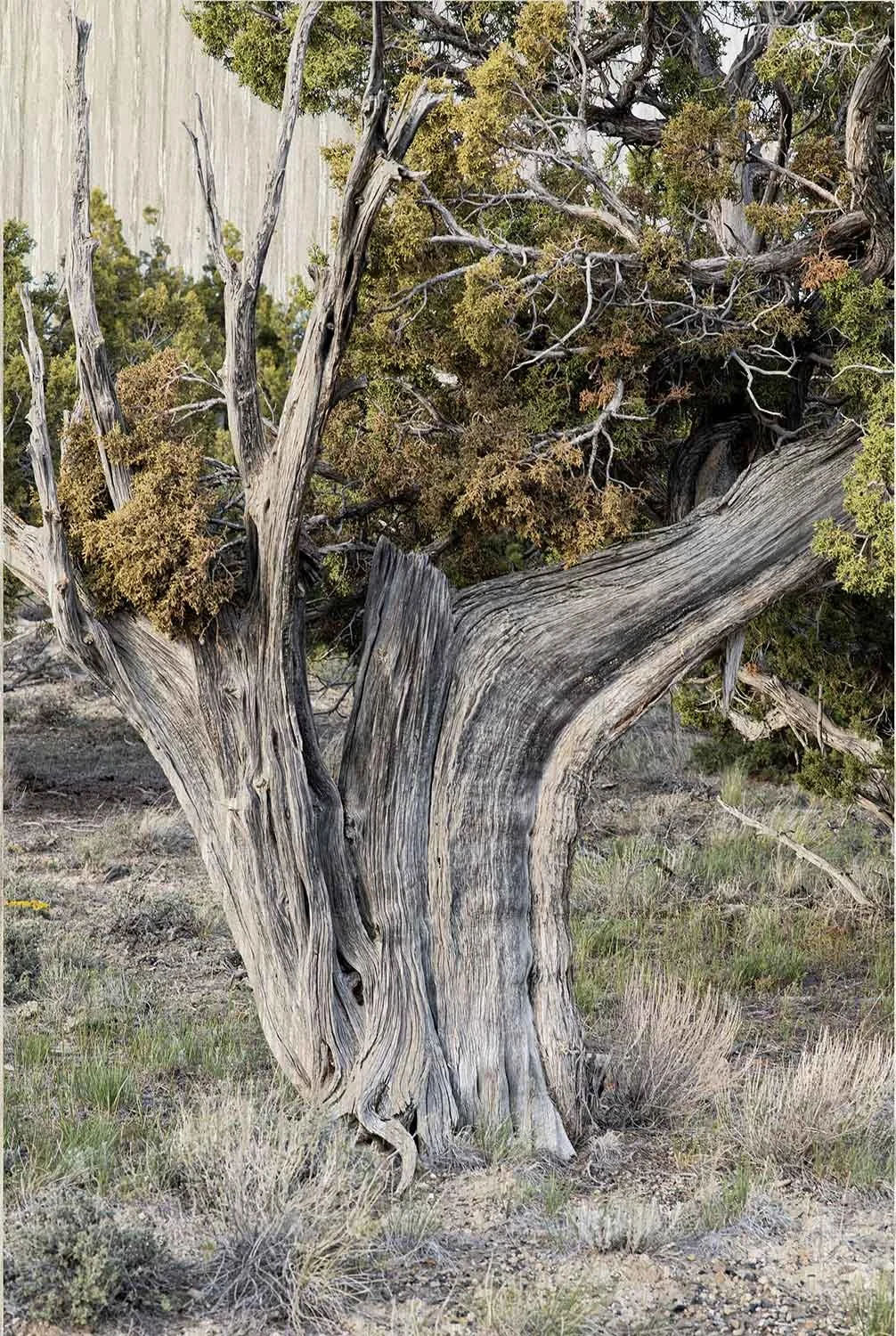

Whereas Lunar Landscape presents a fold as a ripple or a curvature in the texture of the Earth’s surface, Provo, Utah and the Wasatch Range of the Rocky Mountains (2023) sees folds through a more glacial lens. The image features the edge of the city of Provo as its limits approach the obdurate and towering snow-covered Rocky Mountains. You can see the ridges in the mountains where flowing water has worn away sediment and rock over thousands of years to make riverbends. The antiquity of the mountains juxtaposed against the modernity of the city, which itself has visible folds as seen by its streets, suggests, in contrast to Lunar Landscape, that there is an inside/outside distinction in folding and that folds are something that are formed slowly over time or quickly by force. Here, old and new, chance and intention meet and the tension in their incomplete confrontation is where Tillmans eye has its focus.

Wolfgang Tillmans, Watering, a, 2022 Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/Hong Kong; Galerie Buccholz, Berlin/Cologne; and Maureen Paley, London

Of the many natural subjects in the exhibition, Tillmans’ concern with water usage features prominently, bringing an environmental perspective both to folds and the theme of Fold Me writ large. In Watering, a (2022), bottle caps appear to be floating over pebbles, but a closer look reveals that three of the five bottle caps are actually sitting on top of water bottles that have been cut off at the top. The bottle caps lie next to a filled water sachet, which provides an affordable way of carrying water and is common in West Africa where water scarcity is a perennial problem. The inclusion of the water sachet is important because at the same time that it is cheaper, easier and more sanitary to use than a plastic or ceramic water bottle, if not disposed of properly, it contributes heavily to urban pollution. Governments in Africa are therefore pressured to find a way to provide citizens with safe, portable drinking water year round in a way that limits or does not contribute to pollution at all.

And so, the fold here may be more practical than visual. There’s pressure from the inside, the people, and the outside, the environment, to keep drinking water sanitary and portable and to not pollute. You can also read this as a division between the more environmentally sound way to transport water, whether through a sachet or a plastic water bottle, but you’re still left with the question of pollution, as both contribute to it. Watering, a, challenges us to engage with and see beyond the fold to imagine new ways to keep portable water safe to drink and to do so in a way that doesn’t threaten the health of the world. In this way, folding can be a real, practical, generative process.

Wolfgang Tillmans, Seeing the Scintillations of Sirius Through a Defocused Telescope, 2023 (still) Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/Hong Kong; Galerie Buccholz, Berlin/Cologne; and Maureen Paley, London

If a fold is where patterns break or where the unexpected occurs, then Fold Me draws attention to these moments and suggests new ways of conceiving of order. It not only challenges its viewers to look at art in new, transformative ways, but it also invites us to think of our relationship to the natural world differently, whether ecologically or interpersonally. In fact, the exhibition’s acute and broad-scope eye catches us where we least expect it: in the mountains, in the ocean, and even on a sidewalk, suggesting that moments for reconsideration lie everywhere, especially in places where the fabric of existence seems to fold in on itself, so much so that distinctions become naught. In Fold Me, Tillmans doesn’t just show us how expansive the world appears to be, but how expansive it actually is when we look closely, openly, and fearlessly.