In my third look at the life and works of the American artist, Georgia O’Keefe, I want to concentrate on the art she is probably most remembered for, her flower paintings. The depiction of flowers in works of art has always been a popular genre. In past blogs I looked at two famous female artists, Rachel Ruysch (My Daily Art Display October 3rd 2011) and Judith Leyster (My Daily Art Display December 3rd 2013), who were amongst the greatest floral painters of their time. Also from the Netherlands there were the father and son floral painters, Jan van Os and Georgius van Os. At some time, many of the great names in art completed floral works, such as Manet’s lilacs, Monet’s lilies, Hokusai’s cherry blossom, Dürer’s tuft of cowslips, van Gogh’s sunflowers, Fantin-Latour’s roses and so on. So what is so special about O’Keefe’s floral depictions? The answer is that Georgia O’Keefe’s paintings featured close ups of parts of a flower rather than the whole flower and they are stand-alone depictions and not part of a still-life work. She seemed to integrate photographic methodologies such as cropping and close-ups into her floral works. She believed by enlarging the flower the true beauty of the specimen would be hard to ignore. Of her technique she once said:

“…A flower is relatively small. Everyone has many associations with a flower… still, in a way, nobody really sees a flower, really, it is so small….So I said to myself, I’ll paint what I see, but I’ll paint it big and they will be surprised into taking time to look at it, even busy New Yorkers [will] take time to see what I see of flowers. When you [referring to critics and others who wrote about these paintings] took time to really notice my flower you hung all your associations with flowers on my flower as if I think and see what you think and see of the flower, and I don’t…”

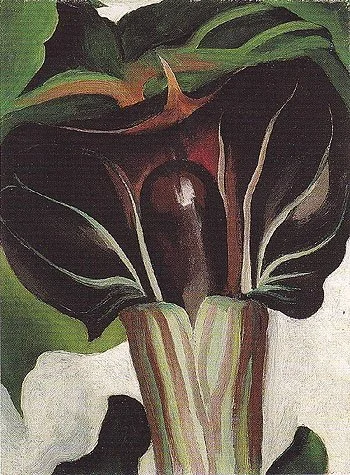

So where did all her ideas for depicting flowers in such a manner start? It could be that she remembered her art teacher she had at her convent school in Madison, back in 1901, when she was fourteen years old. The teacher brought in a wild flower, a jack-in-the-pulpit plant, and asked her teenage students to study it from all angles and told them of the importance of this close scrutiny. O’Keefe was fascinated and drew it from all different angles and then concentrated on drawing just parts of the flower rather than the whole specimen. This was the beginning of her journey into floral painting.

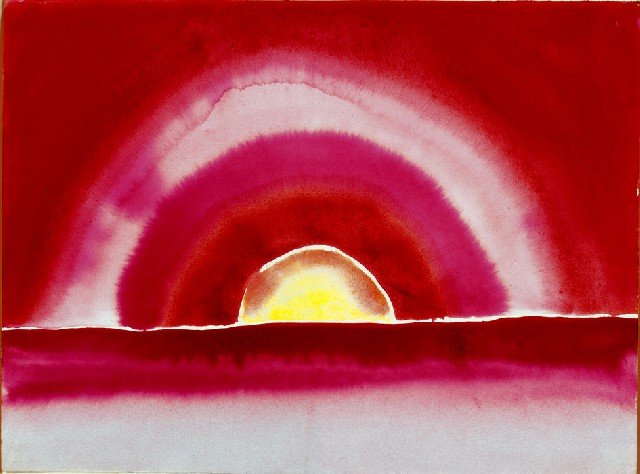

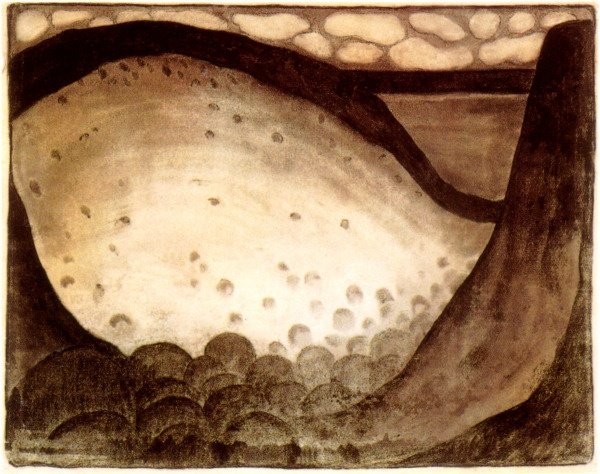

Almost thirty years after this classroom incident, in 1930, Georgia actually completed a series of six painting entitled Jack-in-the Pulpit, five of which can now be found in the National Gallery of Art in Washington. The first in the series began with the striped and hooded bloom and was a carefully detailed botanical depiction of the flower but as the series continued the depiction of the flower moved further away from a realistic depiction of it and became almost mass of colour.

As the series developed, the depictions became less detailed and more of an abstract rendering of the flower with the haloed pistil depicted against a sombre black, purple and gray background. The works shown above show the transition in the way she depicted the flower. In fourth of the series one can see that it has less botanical detail than the first three works and is tending towards abstraction. O’Keefe explained the transition writing:

“…“I found I could say things with color and shapes that I couldn’t say in any other way – things that I had no words for…”

It was around the early 1920’s during her summer visits to Lake George with Alfred Stieglitz that she started painting flowers in her own imitable style. She would concentrate on the head of the flower and “zoom in” on its centre and then enlarged it, so it completely filled the canvas, often cropping the depiction. She painted all types of flowers from the exotic black irises and red Canna lilies to the more mundane such as poppies, daffodils and roses.

The painting Red Canna Lilies, which she completed in 1924 and is now housed in the University of Arizona Museum of Art, has such great magnification it almost appears to be an abstract work of art with just a series of overlapping lines and a myriad of tones.

It was in 1924 that O’Keeffe began to make paintings in various sizes. The one thing they had in common was that all of them tended to focus on the centres of flowers. Petunia No. 2, which she completed that year, was one of her first large-scale flower paintings and she had it accepted into an exhibition organised by Alfred Stieglitz at the Anderson Galleries on Park Avenue, New York. The gallery was owned by the American publisher, Mitchell Kennerley and Stieglitz, who had not had his own exhibition space since 1917, borrowed rooms from Kennerley’s gallery and later in 1925 permanently rented a small room at the gallery which he called the Intimate Gallery. Stieglitz idea for the Intimate Gallery was that it should be a place for local artists to exhibit their work and by so doing create a sense of an artistic community, almost an artist’s cooperative. It was to be a less formal exhibiting place where patron and artists could mix and build up a good working and very personal relationship.

Stieglitz had gathered together a collection of works for his December 1925 exhibition, both artistic and photographic. He had called upon his friends to join him in supplying works for the exhibition. Including himself, there were seven contributors in all. They were John Marin, Marsden Hartley, and Arthur Dove, the modernist painters, the watercolourist Charles Demuth as well as his fellow photographer Paul Strand, and of course, not forgetting his wife, Georgia O’Keefe. The exhibition, at the time, was one of the largest exhibitions of American art ever organised and was entitled Alfred Stieglitz Presents Seven Americans: 159 Paintings, Photographs, and Things, Recent and Never Before Publicly Shown by Arthur G. Dove, Marsden Hartley, John Marin, Charles Demuth, Paul Strand, Georgia O’Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz. The exhibition lasted for three weeks and had numerous visitors but few of the painting sold.

In the mid 1800’s an herbaceous perennial plant, native to southern Africa was introduced into America. It was the Calla Lily. It had such an exotic looking flower that it soon became a favourite subject of floral painters and photographers. Over time Georgia O’Keefe completed numerous renditions of the flower, so much so, the lily became her insignia in the eyes of the public, and the Mexican artist Miguel Covarrubias took up that theme in his caricature of O’Keeffe as “Our Lady of the Lily“, which appeared in the New Yorker in 1929. Two Calla Lilies on Pink was one of her painting depicting this exotic flower. She completed it in 1928 and is an amazing piece of floral art full of subtle merging of colours and tones. The flower petals lie against a pink background which enhances the beauty of the work. Look how O’Keefe has managed to merge a green colour in the white of the petals and by doing so cleverly highlighting them. Again these white and green tinged petals of the two flowers seem to be pierced by the emergence of two bright yellow pistils as they rise upwards. It was this kind of depiction with its sexual connotation that was to lead to controversy. How could floral paintings cause such controversy?

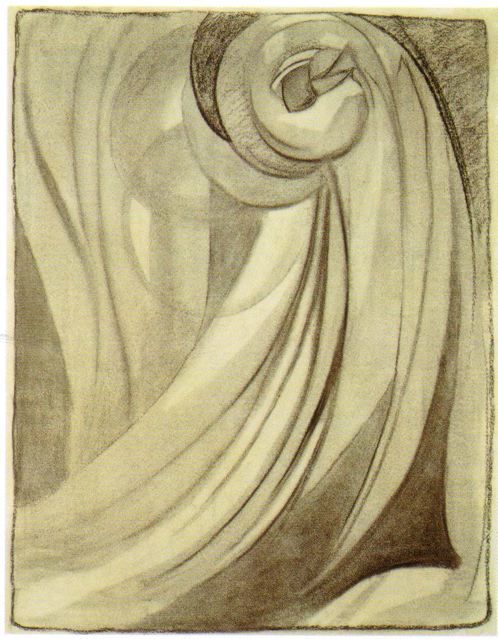

Another example of her work which some people believed lent credence to the sexual nuance of her paintings was one entitled Grey Lines with Black, Blue and Yellow which she completed around 1923 and is part of the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston collection. It is looked upon as one of her best works. Is it a floral painting? Is it a close up of the inner part of a flower? It is this ambiguity which is fascinating and has led some critics to argue that it is an abstract work and that the undulating folds are based upon female genitalia. Georgia O’Keefe was adamant that none of her floral works of art had anything to do with male or female genitalia and grew weary of those people who maintained the sexual link even after she had denied such a connotation. In Ernest Watson’s biography of Georgia, Georgia O’Keefe, American Artist, he tells how, in 1943, she dismisses the sexual association with her floral paintings even if it mean people paid closer attention to the works of art. She is quoted as saying:

“…Well – I made you take time to look at what I saw and when you took time to really notice my flowers you hung all your own associations with flowers on my flower and you write about my flower as if I think and see what you think and see of the flower – and I don’t…”

Some people will not accept what she has said and have ignored her denial of sexuality in her work. Randall Griffin, a Professor in the Department of Art History at Southern Methodist University in Dallas who specialises in American Art History, in his recent biography (Phaidon) on O’Keefe explained in a chapter entitled The Question of Gender:

“…It now seems abundantly clear that, in spite of her vehement denials, O’Keeffe meant some of her paintings (not just the flowers) to look vaginal…..Works such as Abstraction Seaweed and Water – Maine and Flower Abstraction overtly allude to female genitalia…”

So I guess I will leave you to form your own opinion as to the sexuality of her floral works.

In my final look at Georgia O’Keefe’s life and her paintings I will explore her life in the hot desert lands of New Mexico and how it influenced her art.