Not so long ago, if critically touted jazz musicians put out an album of pop-tune covers, they would be roasted—or at least scrutinized—for “selling out.” This would be particularly true if they recorded an album of Beatles covers, in part because the Beatles were the biggest (and thus in this view, the most commercial) pop band of them all; in part because few of their songs are well suited for jazz; and in part because of the evidence: Most stabs at “jazzing” the Beatles have been embarrassments.

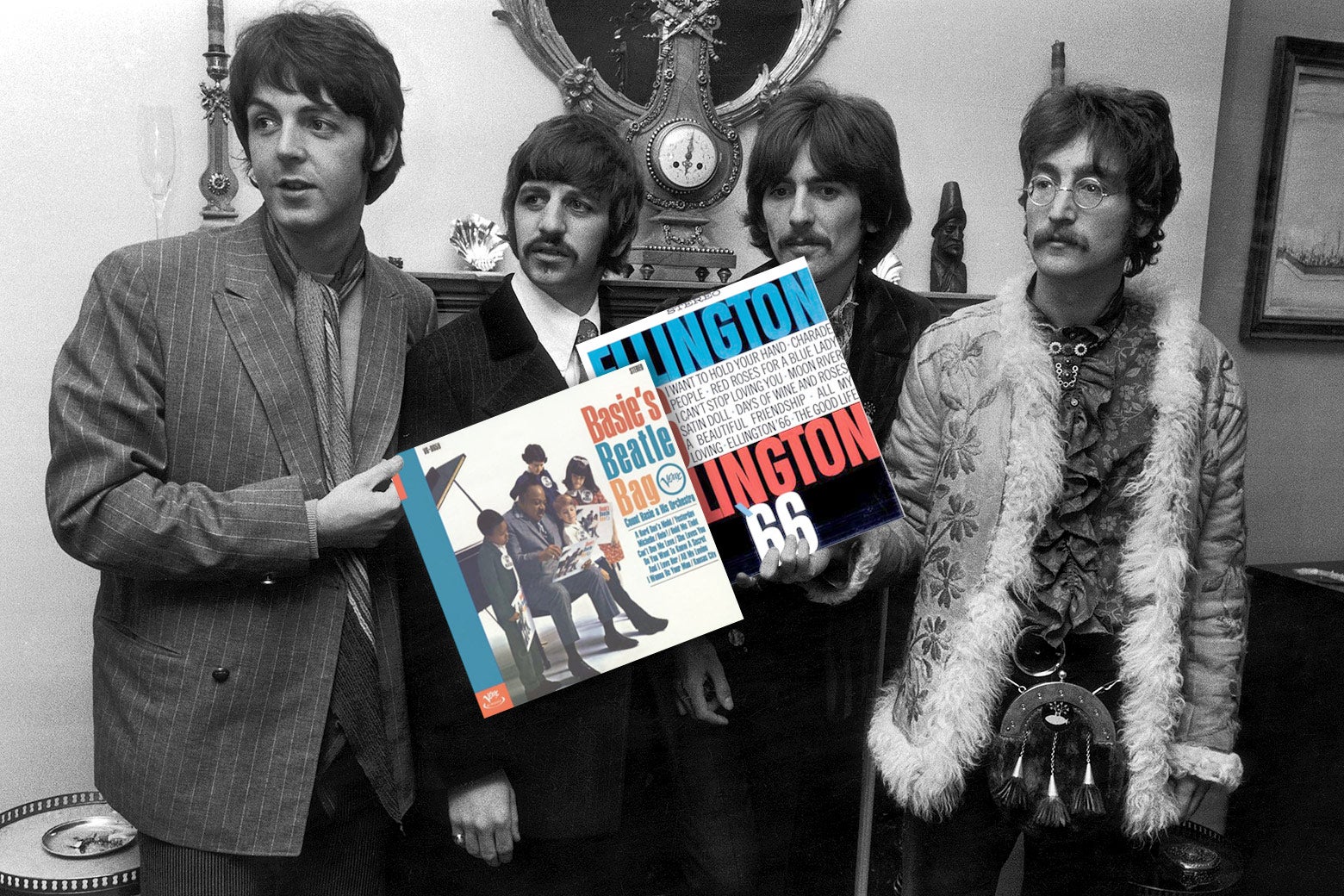

In the mid-to-late 1960s, when rock ’n’ roll started displacing jazz as the predominant form of American popular music, the big record labels started pressuring their artists to do Beatles albums. Soon we had Count Basie’s Beatle Bag, George Benson’s The Other Side of Abbey Road, the two Beatles songs on Ellington ’66, and, as long as a decade later, Sarah Vaughan’s Songs of the Beatles—all sad, boring, mercifully forgotten affairs. Vaughan, one of the most luminous jazz singers ever, sounds miserable and clearly didn’t mind if you noticed.

That said, the latest venture down this long, unwinding road, Your Mother Should Know: Brad Mehldau Plays the Beatles (out Feb. 10 from Nonesuch Records), is something else entirely. For the most part, it’s a delight, even a triumph, and it’s worth exploring why.

First, we should dispose of the notion that covering pop tunes is inherently a betrayal of the jazz tradition. The idea was put forth most fiercely by the late Stanley Crouch, who blasted Miles Davis’ music of the 1970s and ’80s as “an abject surrender to popular trends.” In this view, the cardinal sin occurred when Davis—one of the most innovative jazz musicians of all time—brought in electric guitars, synth keyboards, and funk rhythms. When Davis recruited a go-go drummer and started playing outright pop tunes, like Michael Jackson’s “Human Nature” and Cyndi Lauper’s “Time After Time,” Crouch (and he wasn’t alone here) went berserk, condemning the new sound as “so decadent that it can no longer disguise the shriveling of its maker’s soul.”

Where Crouch—a brilliant but cantankerous critic, and a sometime contributor to Slate—went wrong was in forgetting that the “jazz standards” of the 1940s and ’50s, which every jazz musician was expected to play (e.g., “My Funny Valentine,” “Body and Soul,” “All the Things You Are,” “Embraceable You”), were the pop tunes of their day, many of them originating in Broadway musicals, which were a major source of jukebox and record-store hits.

Davis was 18 years old in 1944, when Victor Young wrote “Stella by Starlight.” He was playing trumpet in New York jazz clubs by the time Harry James popularized the song in 1947. It was only natural that the jazz giants of the day—Charlie Parker, Stan Getz, Chet Baker, Bud Powell, and eventually Davis himself—covered the tune. It was one of the songs they’d been listening to; why shouldn’t they play it?

Brad Mehldau was born in 1970. He and the many other jazz musicians of his generation grew up listening to Parker, Davis, and the other giants playing standards. But they were also listening to the pop tunes of their formative years: songs by James Brown, Prince, Stevie Wonder, and Radiohead, as well as hip-hop, rap, and, yes, the Beatles. So why shouldn’t they be inspired by—why shouldn’t they play—those songs as well?

This isn’t to say, necessarily, that this music rivals the best pieces by Rodgers and Hart, Gershwin, or Jerome Kern (though a case could be made that some of it does). But it’s daft to argue that adapting some of this music for jazz is somehow illegitimate or nothing more than pandering. (Davis, who went electric a few years after Dylan did, was trying to attract younger audiences, but he had always been on the lookout for new forms. His turn to rock fusion, then pop, was just one of the four or five times he changed the course of jazz.)

Which takes us back to Mehldau and his Beatles album. In his forthcoming memoir, Formation, Mehldau notes that he didn’t listen much to the Beatles as a kid. His first pop-music hero was Billy Joel. (The saxophone and trumpet solos on The Stranger and 52nd Street, by Phil Woods and Freddie Hubbard, respectively, were 10-year-old Brad’s first exposures to jazz.) By age 13, he was dipping into John Coltrane and Jimi Hendrix while studying classical piano at a serious summer camp.

The upshot is that by the time Mehldau took a close look at the Beatles, in his 20s, he appreciated not just their joyous rhythms and hook-jammed melodies, but still more, their inventive harmonies, especially on the later albums, starting with Revolver and Rubber Soul.

[Read: When the Beatles Made Their Avant-Garde R&B Album.]

This is what the jazz giants who made Beatles albums under duress in the ’60s didn’t understand. They dismissed the Fab Four as mop-headed kids singing silly songs for other mop-headed kids. Basie thought swelling “A Hard Day’s Night” with loud horns and a swing drummer would fill the terms of his contract. Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn seemed to be mocking McCartney and Lennon with their wah-wah-bleated melodies on “I Want to Hold Your Hand.” They saw these projects as a step down, and so did everybody else: Traditional jazz fans weren’t interested, and Beatles fans didn’t even notice, except maybe to chuckle in derision.

It helps that Mehldau is one of the top handful of jazz pianists on today’s scene. He can play any kind of music with idiomatic flavor, his touch is pristine, his rhythm dexterous, and his sense of harmony—the key thing here—colorful and rich.

Your Mother Should Know isn’t the first time he has traversed the Beatles’ catalog. In 1996, on The Art of the Trio, Vol. 1, an album that otherwise consists of original pieces and jazz standards, he strung out an adventurous, sprightly cover of “Blackbird.” On 2005’s Day Is Done, alongside some standards and covers of Nick Drake, Paul Simon, and Radiohead, he unleashed some Baroque-on-fire counterpoint on “Martha My Dear.” In 2012, on Blues & Ballads, he coaxed a calmer, more lyrical rendition of “And I Love Her.”

But this is the first time Mehldau has investigated just one pop band on an album and, riskier still, has done so in a solo live concert (at the Philharmonie de Paris, where, a few years earlier, he recorded a program of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier interspersed with his own variations). A further risk, though telling, is that he passes over the Beatles’ most familiar hits for songs, including the title piece, that some younger listeners—who, like him, were born after the Beatles broke up—might not know (though their mothers do).

The album’s first track is “I Am the Walrus” (which, like the title tune, comes from Magical Mystery Tour). As Mehldau explains in an enlightening YouTube video, it’s one of their “strangest” tunes—in terms of both harmony and the length of its melodic phrases, opening with a descending whole-tone scale straight out of Impressionist music (Ravel, Debussy), which fits Mehldau’s romantic-virtuoso tendencies. It’s mesmerizing, magical: heady and emotional at once. He transforms a song that’s been commonly viewed as a curiosity into a classic.

Then comes the title tune, a song heavily influenced by the British music-hall ditties that Paul McCartney heard growing up, but emphasizing “dotted notes,” which stretch the normal duration of a note, adding syncopation, tension, and a certain swing. Mehldau accents the dots with extra stress and laces them with improvisations on old and new styles.

Mehldau turns “For No One” (from Revolver), an oddly pensive Beatles song, into a gorgeous meditation, slowing the melody, embellishing the harmony, wrapping each around the other. He spins “She Said She Said” (from the same album), an acid-inspired rouser (“I know what it’s like to be dead” is the rhyme), into a dream, pocked with the hint of a nightmare by ringing high notes and a melancholic bassline. “Here, There, and Everywhere” (another Revolver standout) is a searching ballad. “If I Needed Someone” (Rubber Soul) is a lament that he lends a Sondheim vibe. “Golden Slumbers” (from Abbey Road), he presents as a straight recitation. He ends, for reasons not quite clear, with an elegiac cover of David Bowie’s “Life on Mars.”

All of these pieces do what covers are supposed to do—illuminate certain aspects of a song that we hadn’t noticed before, trace entirely new angles that give the song a flavor it never had, and do so in (or commenting on) the spirit of the original while imposing the interpreter’s distinct voice. If it’s a jazz cover, it should also lay at least a hint of swing or the blues.

Not all 10 of the album’s Beatles tracks are successes. “I Saw Her Standing There” (from the Beatles’ first album) should swing a lot more than the original to justify its place here, but this doesn’t. “Baby’s in Black” (from Beatles for Sale) isn’t an interesting enough piece to undergird Mehldau’s soul blues treatment. (It’s unclear why Mehldau chose these two, as they don’t at all fit his penchant for “strange” songs.) “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer,” a dud on Abbey Road, doesn’t fare much better here.

In jazz and much else, as the great bandleader Jimmie Lunceford once put it, “ ’T’aint what you do, it’s the way you do it,” and even purists should have realized long ago that rock and modern pop tunes are among the things jazz musicians can do if they do it right.

Herbie Hancock, Fred Hersch, and Dave Douglas have played wonderful covers of Joni Mitchell (a songwriter with a demonstrated jazz sensibility). The Bad Plus sparked a career doing high-spirit covers of Nirvana, ABBA, and Blondie. The list could go on and on and on. There are even some other good Beatles covers. On 2019’s A Day in the Life, an assortment of young jazz musicians, including Mary Halvorson, Sullivan Fortner, and Makaya McCraven, take dizzy spins with the tunes from Sgt. Pepper.

And those Miles Davis covers of Michael Jackson and Cyndi Lauper that Stanley Crouch so despised? The studio versions are dreary, but when he and his go-go band played them in concerts, which I saw several times (the highlights are collected on the posthumous album Live Around the World), they were terrific, as deserving of a spot in his pantheon as his more traditional “standards”—a word that should be either greatly expanded or dropped from the musical lexicon.