West Bay is a small coastal town in west Dorset, formerly known as Bridport Harbour. The name was changed on the coming of the railway in 1884, with the hope of attracting tourists to the fledgling resort, previously little more than a fishing village and harbour for exporting the ropes and nets from Bridport for which the town was famous.

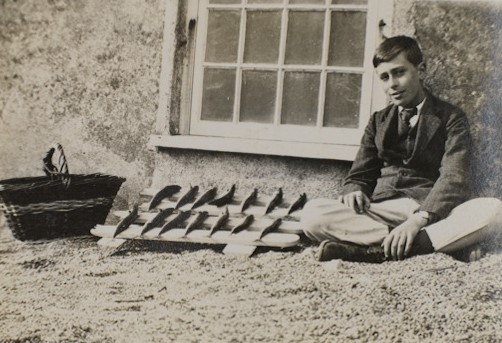

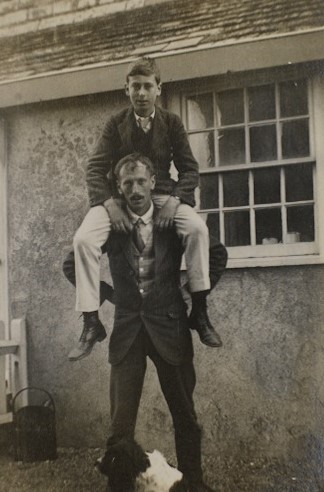

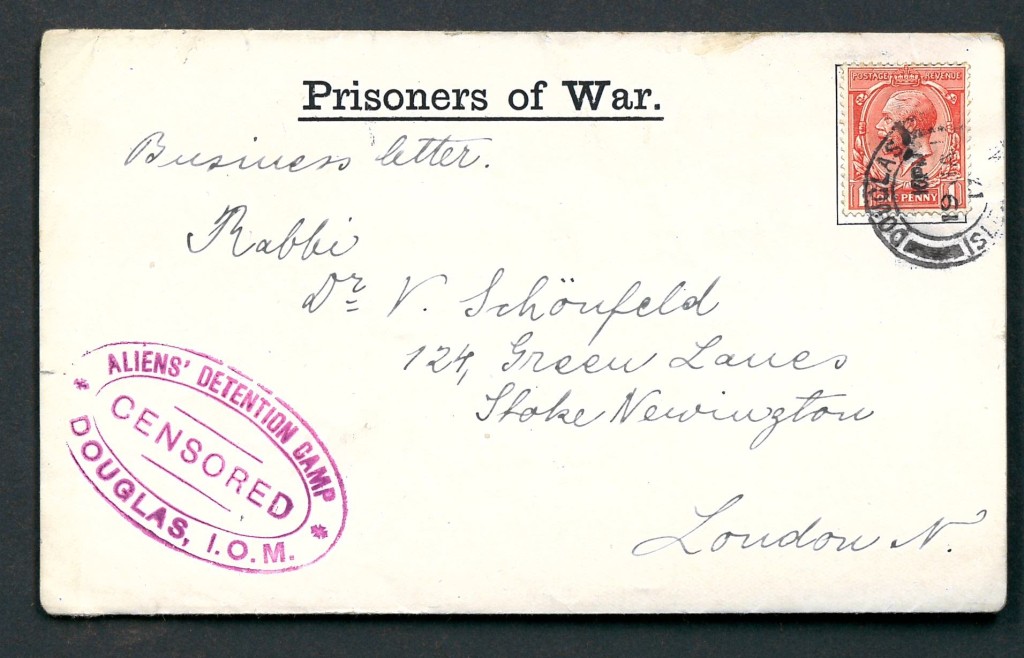

In 1914, Prince Louis Francis of Battenberg, later to become Earl Mountbatten of Burma, was a cadet at Osborne Naval College on the Isle of Wight. At that time naval cadets spent a couple of years at Osborne before going on to Dartmouth. Dickie seems to have enjoyed his stay at Osborne, where he took many photographs of the activities there and of his special friends (see album MS62/MB/2/N2.) However, conditions for the boys were not good, and there appears to have been health problems including frequent outbreaks of “pinkeye”, or conjunctivitis, more serious in the days before antibiotics. In early 1914 young Battenberg became ill with bronchitis and whooping cough, so it was decided to send him to West Bay with a tutor to recuperate. Miss Nona Kerr (later Mrs Richard Crichton) was lady in waiting to Prince Louis’s mother, Princess Victoria of Battenberg, a granddaughter of Queen Victoria. Nona’s sister was married to Canon Wickham, the rector of Bradford Abbas, a parish in north Dorset, and the owner of a cottage called “The Bunker” in West Bay which he was happy to lend. A temporary tutor, F. Lawrence Long, was engaged and Dickie moved into his holiday home. Mr Long, a friendly young man, had previously been a master at Gladstone’s School in London.

The cottage was built right on the shingle beach, and still exists, now called Gull House. It adjoins a smaller cottage called The Dinghy. Dickie took many photographs, both inside and out, as well as of the nearby beach, harbour and cliffs. He put them into a small cloth-bound album with an art nouveau style cartouche, along with 10 commercial postcards of West Bay. This is now part of the Broadlands Archive [MS62/MB/2/N3]. Mountbatten would still recognise the exterior of the cottage, now painted a deep pink, but the thatched roof has been replaced with tiles. Property websites suggest it could now be worth nearly a million pounds, recognising the great popularity of West Bay, partly due to the “Broadchurch effect”; Broadchurch being a recent ITV detective series starring David Tennant, Olivia Coleman and Jodie Whittaker. This ran to three series altogether, all set in and near West Bay. Series two included Charlotte Rampling as a barrister, while series three starred Julie Hesmondhalgh as the victim of a serious assault.

Some years earlier West Bay was also used as the location for the television series Harbour Lights, starring Nick Berry as the harbour master. Back in the 1970s the beach was the setting for the credits at the beginning of The Rise and Fall of Reginald Perrin, starring Leonard Rossiter. Reginald was shown rapidly divesting himself of his clothes, including underpants, and swimming out to sea to fake his own death and start a new life. East Cliff is clearly visible in this scene but Gull House is out of shot.

East Cliff, West Bay

The main feature of the landscape of West Bay is the iconic East Cliff, a striking landmark of vertical Bridport sandstone. This was photographed to good effect many times during the filming of Broadchurch. The sandstone is notoriously unstable and there have been many major rock falls in recent years, some sadly resulting in fatalities. The geology of West Cliff is different, but also unstable, and Dickie photographed small examples of landslips here, caused by the juxtaposition of permeable and impermeable rocks, as in the Lyme Regis area further west. Dickie did not photograph East Cliff, probably because the best shots need to be taken out at sea. Dickie did go out in a boat, but probably decided it was safer to leave his precious camera behind. He would not recognise the harbour now. It has been remodelled in recent years, to protect it from the south-west swells which had been a serious problem for earlier shipping. Originally it was approached from the sea by two moles or piers protecting the entrance channel, but this was never very satisfactory so it was decided to completely redesign it. Work finished in 2004.

Pier Terrace

Dickie’s visit wasn’t the first time that members of the Battenberg family had stayed in West Bay. Some years previously Dickie’s parents, Prince Louis and Princess Victoria, had stayed in an apartment forming part of Pier Terrace, when Prince Louis’ ship was stationed at Weymouth. Pier Terrace is a rather incongruous large building of four storeys with a mansard roof, right in the middle of the small town. It was built in 1885 by the Arts and Crafts architect E. S. Prior, in the hope of attracting more tourists. It still dominates the harbour though it is now balanced by modern luxury flats on the far side of the harbour.

Jo Draper describes West Bay as “an odd place, difficult to define. A village sized seaside resort in a fine situation” (Dorset, the complete guide). John Hyams expressed similar sentiments in his book Dorset, published in 1970: “West Bay one must confess to be a curiosity, however seriously it takes itself. For centuries attempts were made to establish a port at the mouth of the Brit, only to be frustrated time and time again by by the sea’s annoying habit of silting it up.“ Eventually a harbour was constructed in the 18th century, though silt was always a problem, controlled by hatches on the river allowing the silt to be scoured away. Hyam goes on “it sets out determinedly to become another Blackpool, complete with kiosks of garish merchandise and ice cream…. westward an esplanade creeps like a choking tendril along the foot of West Cliff.”.

A number of celebrities have made their homes in or near West Bay, including the widow of Cubby Broccoli, the producer of the James Bond films, who once owned a large house there. The actor Pauline Quirke was so taken with the area while filming for Broadchurch that she acquired an apartment. West Bay was the victim of serious winter floods during the 1990s, so many tons of

shingle were recently imported to create a high barrier against the sea, ensuring the safety of the little town for the time being. The harbour is still used by fishing boats including small trawlers from as far afield as Padstow, which explains the strong smell of fish! Lobster and crab pots are piled up on the quayside. There are also many pleasure craft moored there.

Today the small chapel has been converted into a museum for the town, with activities for children and other events. There was a shipbuilding industry here in the 19th century. The historic Salt House was used to store salt, acting as ballast on the outward voyage to Newfoundland, returning with salted cod. Substantial warehouse buildings remain as reminders of West Bay’s former

importance as a port. As one would expect, there are numerous cafes and restaurants, while many small shops cater for the needs of holidaymakers. Parking is predictably expensive, but there is plenty of it.

![Letterpress halftone portrait photograph of Admiral Prince Louis of Battenberg when First Sea Lord, 1914 [MB2/A12/61]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/ms62_mb2_a12_61.jpg?w=500)

![Black and white photograph of Prince Louis Alexander of Battenberg and his sons, Louis (on the left) and George (on the right), 1914 [MB2/A12/34]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/ms62_mb2_a12_34.jpg?w=500)

![Black and white photograph of the officers and midshipmen of HMS Lion including Prince Louis Francis of Battenberg (later Lord Mountbatten), 1916 [MB2/A12/65]. He can be seen in the uniform of a midshipman, seated cross-legged in the middle of the front row, tenth from the left. He is holding a small dog, probably the ship's mascot.](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/ms62_mb2_a12_65.jpg?w=500)

![Photographs of Mountbatten’s parents on their wedding day, 30 April 1884, from the album of Prince Louis of Battenberg [MS 62 MB2/A4/4-5]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2017/02/blogmb2-a4_0004.jpg?w=300)

![Photo of the Princesses of Hesse in 1885, from the album of Prince Louis of Battenberg [MS 62 MB2/A4/6]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2017/02/blogmb2-a4_0006.jpg?w=300)

![Photograph of the Battenberg family c. 1902 from the album of Victoria, Princess Louis of Battenberg, 1901-10 [MS 62 MB2/B2/6]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2017/02/mb2-b2-photos_0006.jpg?w=250)

![Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268168_f26eed63ef_s.jpg)

![Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079577_3b7acbde42_s.jpg)

![Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268523_4f2c587220_s.jpg)

![Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079692_28114e9c7d_s.jpg)