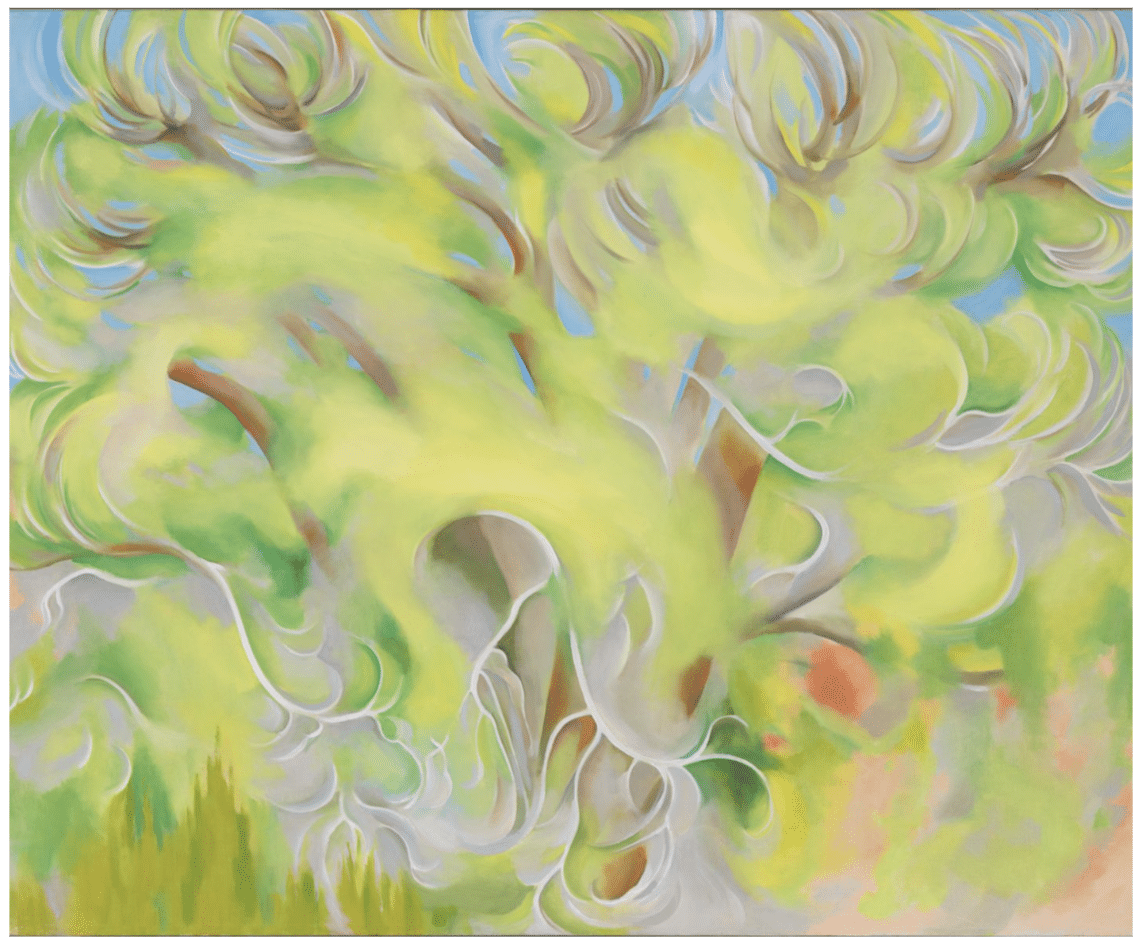

#1. Look Close, See Big

“I wish you could see what I see out the window,” wrote Georgia O’Keeffe to her friend, the painter Arthur Dove in 1942. At 55 years old, she was writing from her solitary ranch house in New Mexico.

Though she’d keep making art for another four decades, neither her vision of artist’s role, nor her eye for abundant and meaningful beauty, would waver.

“The earth pink and yellow cliffs to the north—the full pale moon about to go down in an early morning lavender sky behind a very long beautiful tree covered mesa to the west—pink and purple hills in front and the scrubby fine dull green cedars—and a feeling of much space—It is a very beautiful world.”

O’Keeffe saw big; she took in nature at the cosmic scale, yet she simultaneously parsed the landscape on an intimate personal level.

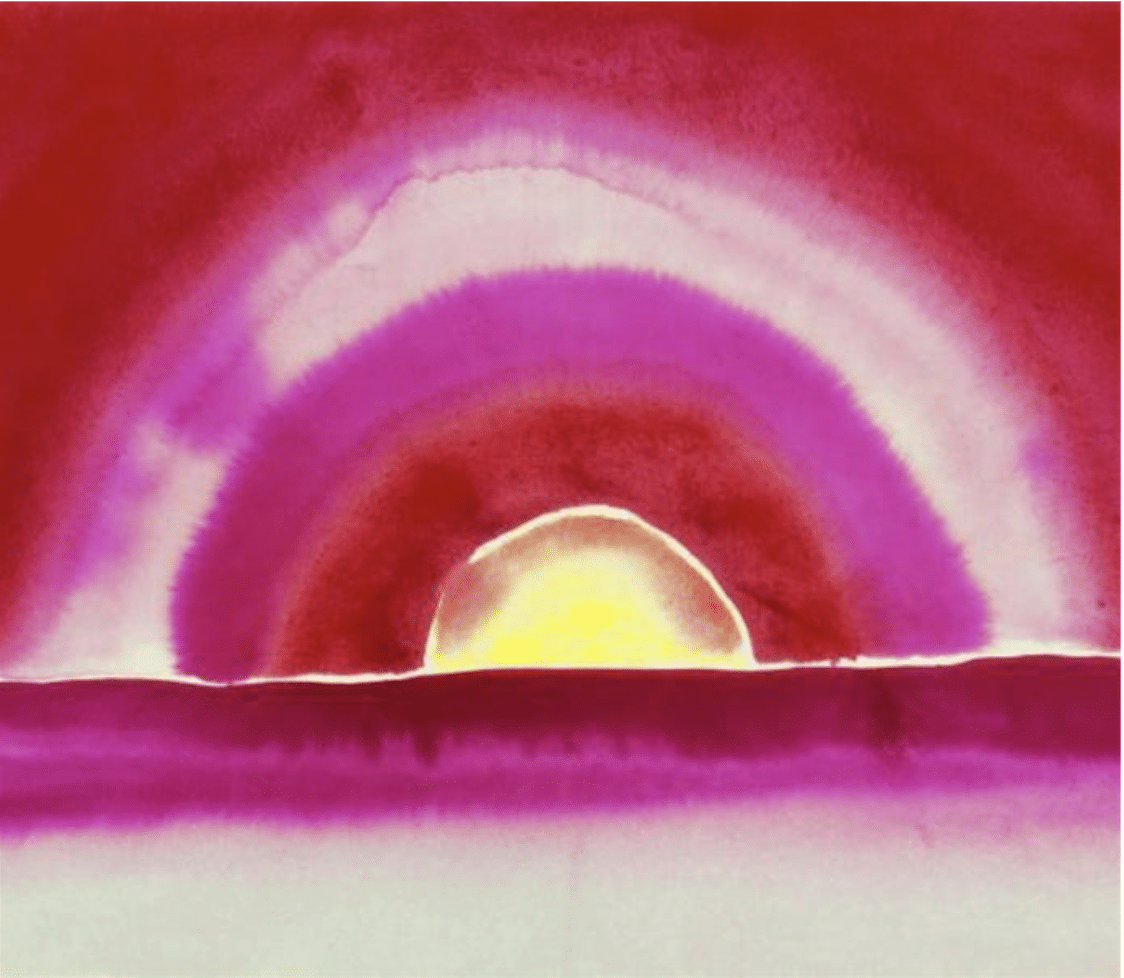

Georgia O’Keeffe, Sunrise, 1916

On top of close looking and big feeling, she reveled in relating observed details to each other on her canvases, exploring relationships between the colors, lines, and shapes that interested her. Like William Blake, she trained herself to “see the world in a grain of sand” and shared that vision with the world.

“It is only by selection, by elimination, by emphasis,” she said in 1922, “that we get at the real meaning of things.”

#2. Fail and Fail Again

“Whether you succeed or not is irrelevant,” O’Keeffe wrote to writer Sherwood Anderson. “There is no such thing.”

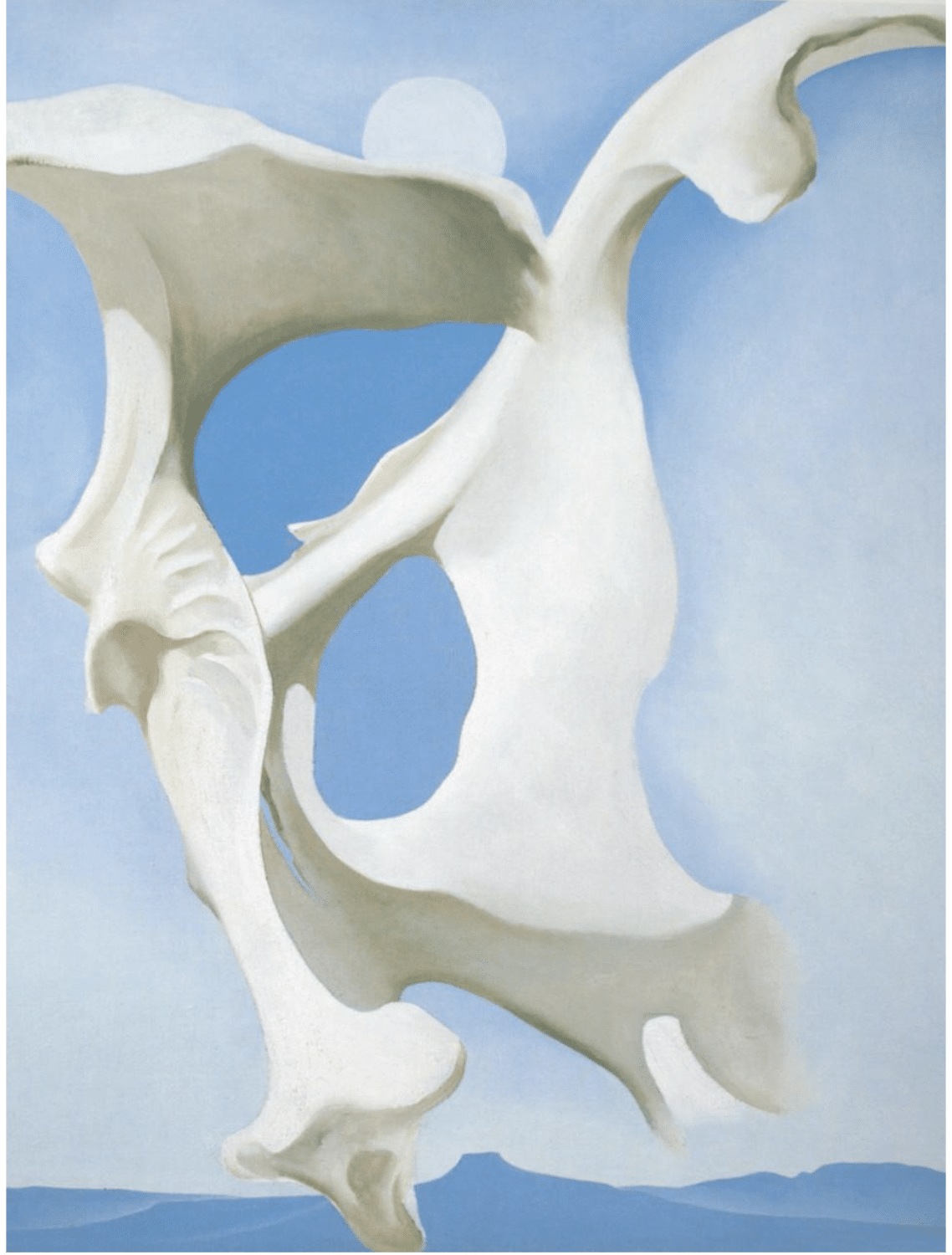

Pelvis With The Moon by Georgia O Keeffe

O’Keeffe realized every artist makes bad work and that setbacks and misfires come with the territory. She knew playing the long game is an essential part of the process. “Success doesn’t come with painting one picture. It results from taking a certain definite line of action and staying with it,” she told art historian Katharine Kuh.

O’Keeffe worked on an idea for a long time, often painting the same objects and scenes over and over again until she found a composition that she liked. And even when a painting was doomed to never see “success” in the eyes of an audience, she’d finish it and keep it for herself even if, as she once said, “it may not be anything for anyone but me.”

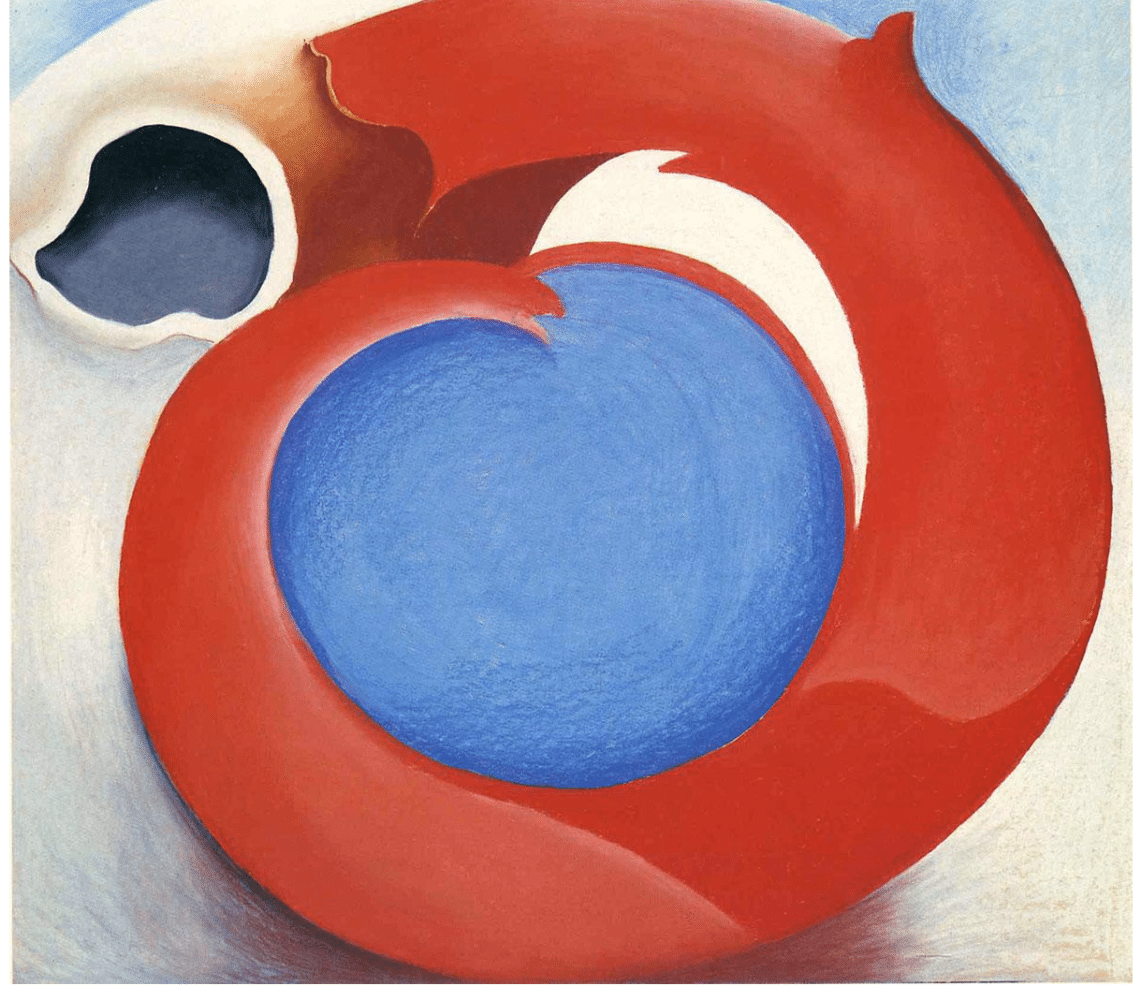

Georgia O’Keeffe, Goat’s Horn with Red, 1945

#3. Make Your Own Freedom (and Never Look Back)

O’Keeffe didn’t bother with what her peers thought of her work. She worked in a time when to call a “serious” painting “beautiful” or “pretty” was a backhanded compliment, if not an insult. But O’Keeffe devoted herself to depicting the wild beauty of nature in vibrant colors. “I’m one of the few artists, maybe the only one today, who is willing to talk about my work as pretty,” she once said. “I don’t mind it being pretty.”

The men in the circle of artists she moved in particularly disapproved. “The men didn’t like my color,” she recalled. “My color was hopeless. My color was too bright.” What did she think? “I liked colors,” she said. End of discussion.

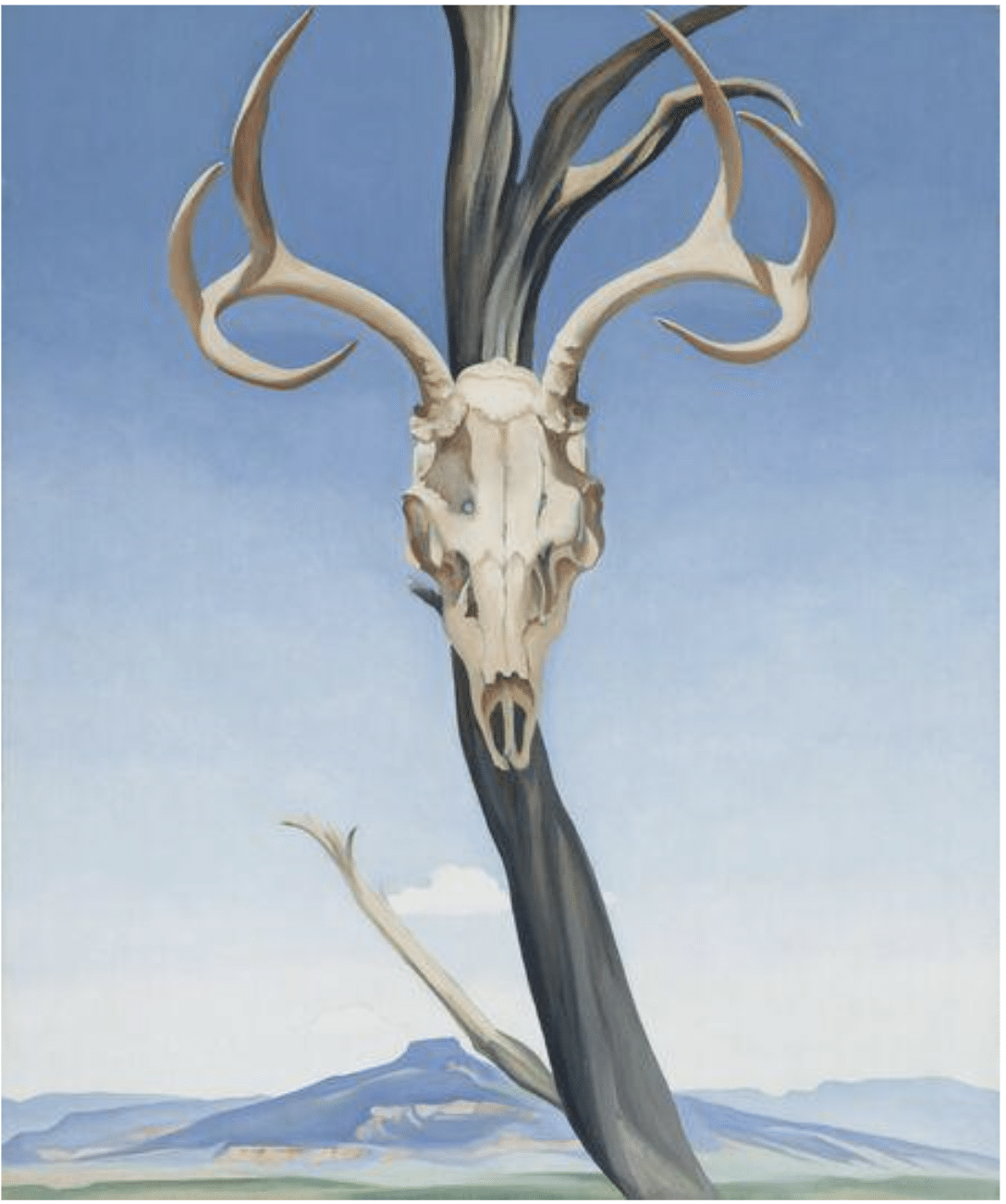

Georgia O’Keeffe, Deer’s Skull with Pedernal, 1936. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

O’Keeffe demanded freedom. She went her own way all her life, and when it came to choosing a place to grow her career, she opted for what for anyone else would have been a career-killing home base, literally working in a remote desert. She kept aloof from art world drama and spurned any and all commercial and artistic trends. She even designed and made her own clothes.

She created her own freedom, a world in every way of her own making, where she took her work as seriously as she loved and took joy in it. “I was just trying to say what I wanted to say,” she wrote to her friend Anita Pollitzer after a long day spent joyfully nonstop at the easel. “And it is so much fun to say what you want to.”

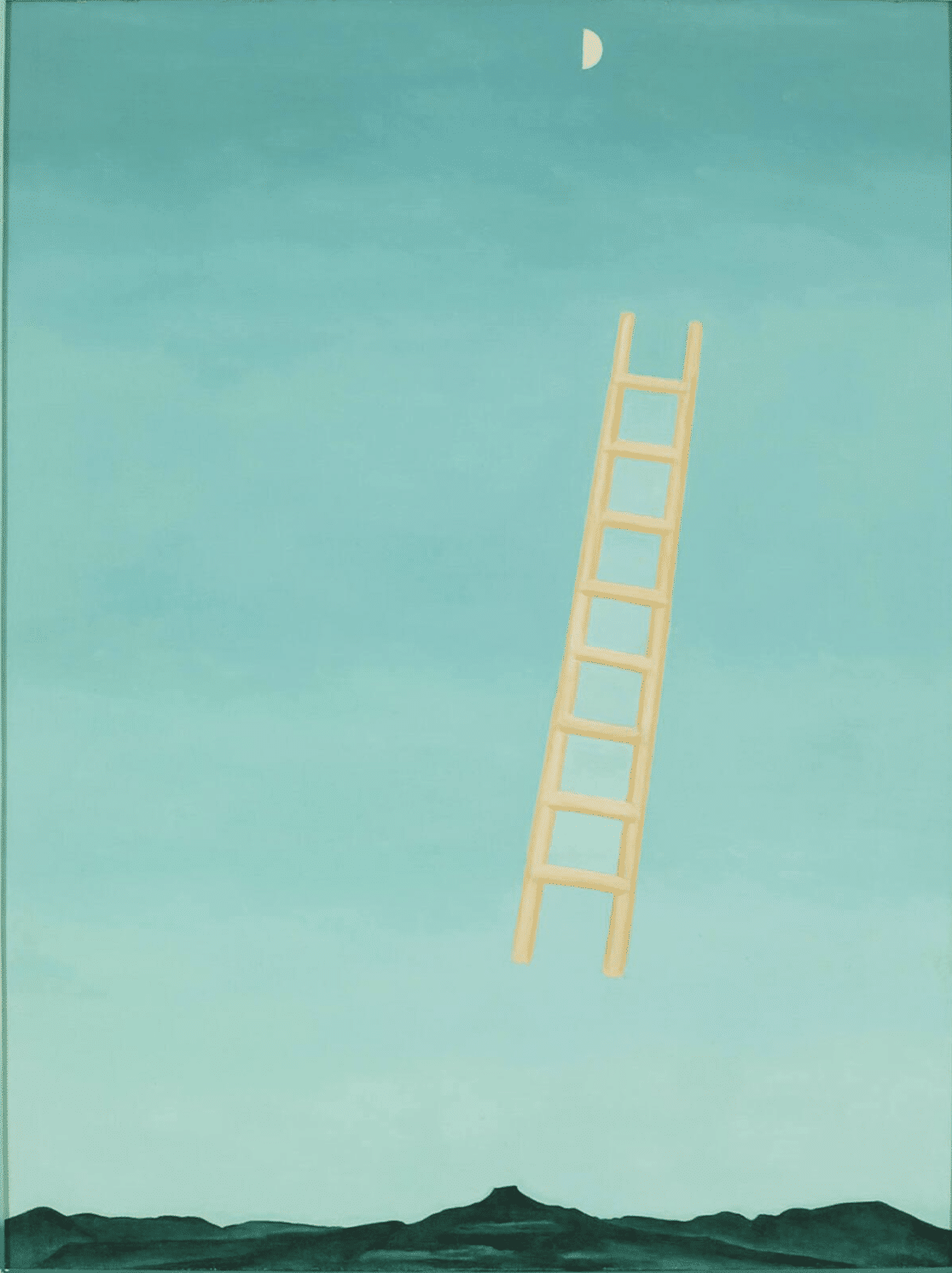

Georgia O’Keeffe, Ladder to the moon

Discovering the joy of “saying what you want to” is what learning to make art is all about.

Perhaps Larrry Moore’s video, The Creativity Course, may hold a key for you. Learn about it here.

Tips from Paul Klee, 20th Century Master of the Imaginary

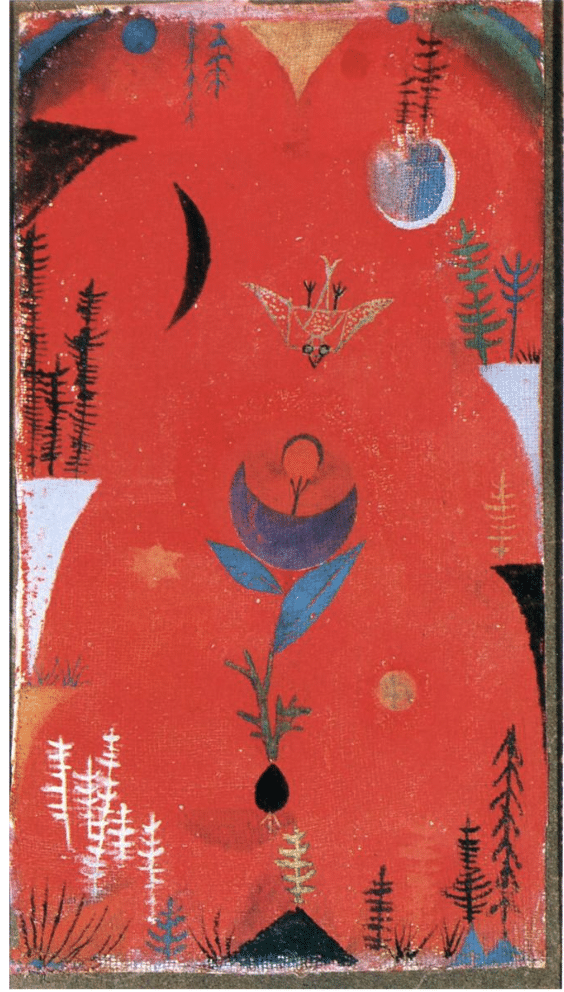

Paul Klee, Flower Myth, 1918

Paul Klee was among the celebrated artists of the 20th century. He taught and wrote prolifically, serving as a leading faculty member of the German Bauhaus school during the 1920s.

Art history recognizes Klee as a major father of abstraction as well as one of the originators of surrealism. His influence stretches through multiple generations of European and American artists, from the influential German Bauhaus school of art and design, through European Modernism and French Surrealism, all the way to the mid-century abstractions of Jackson Pollock, Rothko, and Motherwell. Even the painters of the Pop and Op Art movements of the 1960s owed something to Klee for demonstrating the potential for exuberance and beauty-in-simplicity of the two-dimensional color field.

This vast influence aside, Klee’s work is beloved for its combination of whimsical, intuitive and mystical elements, as though his imagery emanated from the same buried psychological sources as fairytales, mythology, and our own most mysterious dreams. Klee wrote and spoke inspiringly of the deep sources of creativity, yet he also taught and published highly technical and original step-by-step lessons on composition, perspective, and design. His 3,900 pages of lecture notes were distilled into Klee’s Pedagogical Sketchbook published in 1925.

Here are three hints on art and design from Klee.

- “Like people, a picture has a skeleton, muscles and skin.”

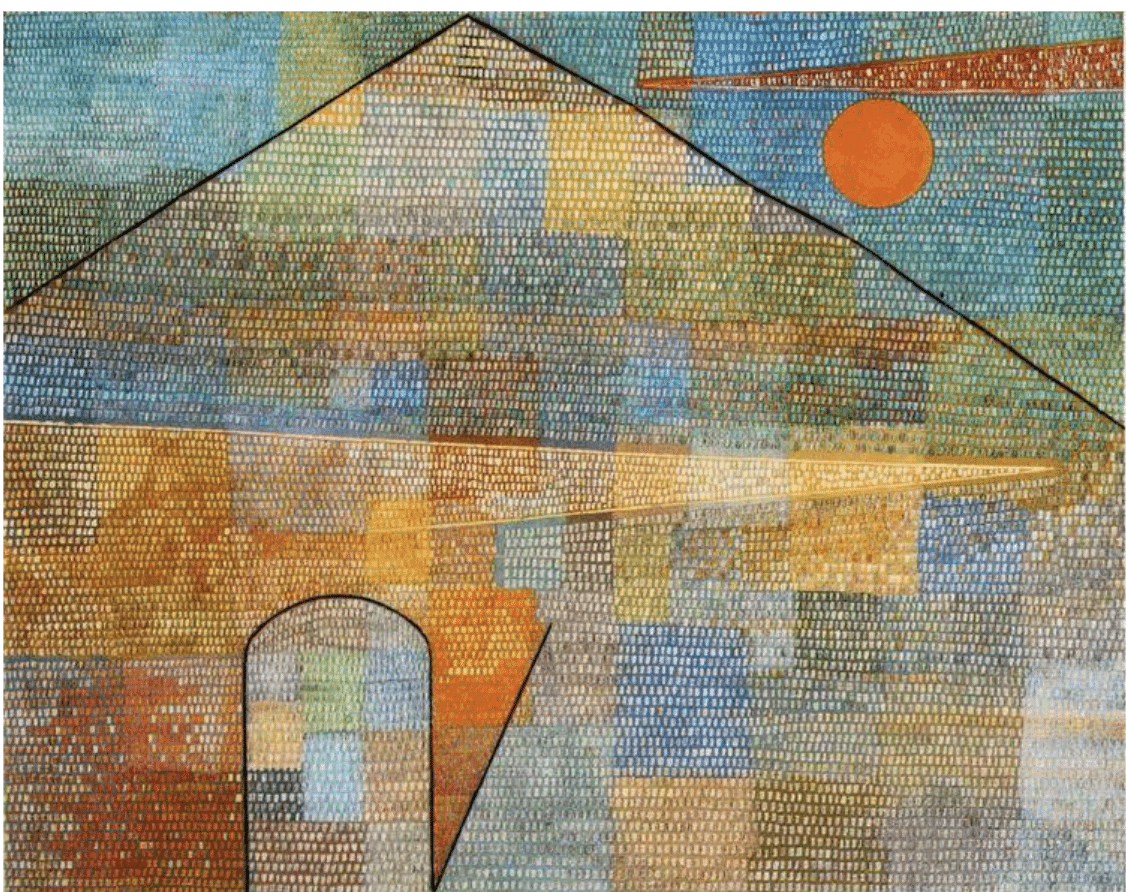

As a leading artist of early 20th century Modernism, Klee was deeply interested in abstraction. A “skeleton” of geometry underlies his compositions, over which the paintings’ lines, shapes, colors and space interact with simple graphical elements, all “set in motion by energy from the artist’s mind,” as one scholar described it.

Paul Klee, To Parnassus, 1932

- “A drawing is a line going for a walk.”

In Klee’s approach to artmaking, the line is animated with movement, spontaneity, and even an element of magic. Composition is founded in geometry, but the line is personal, imperfect, improvisational, even vulnerable in Klee. By “going for a walk,” Klee meant allowing line to have its own magical life, to draw as much by relying on the unconscious, as much as the conscious, mind. Rarely before had the “artist’s hand” been allowed such personality and frank individuality in painting.

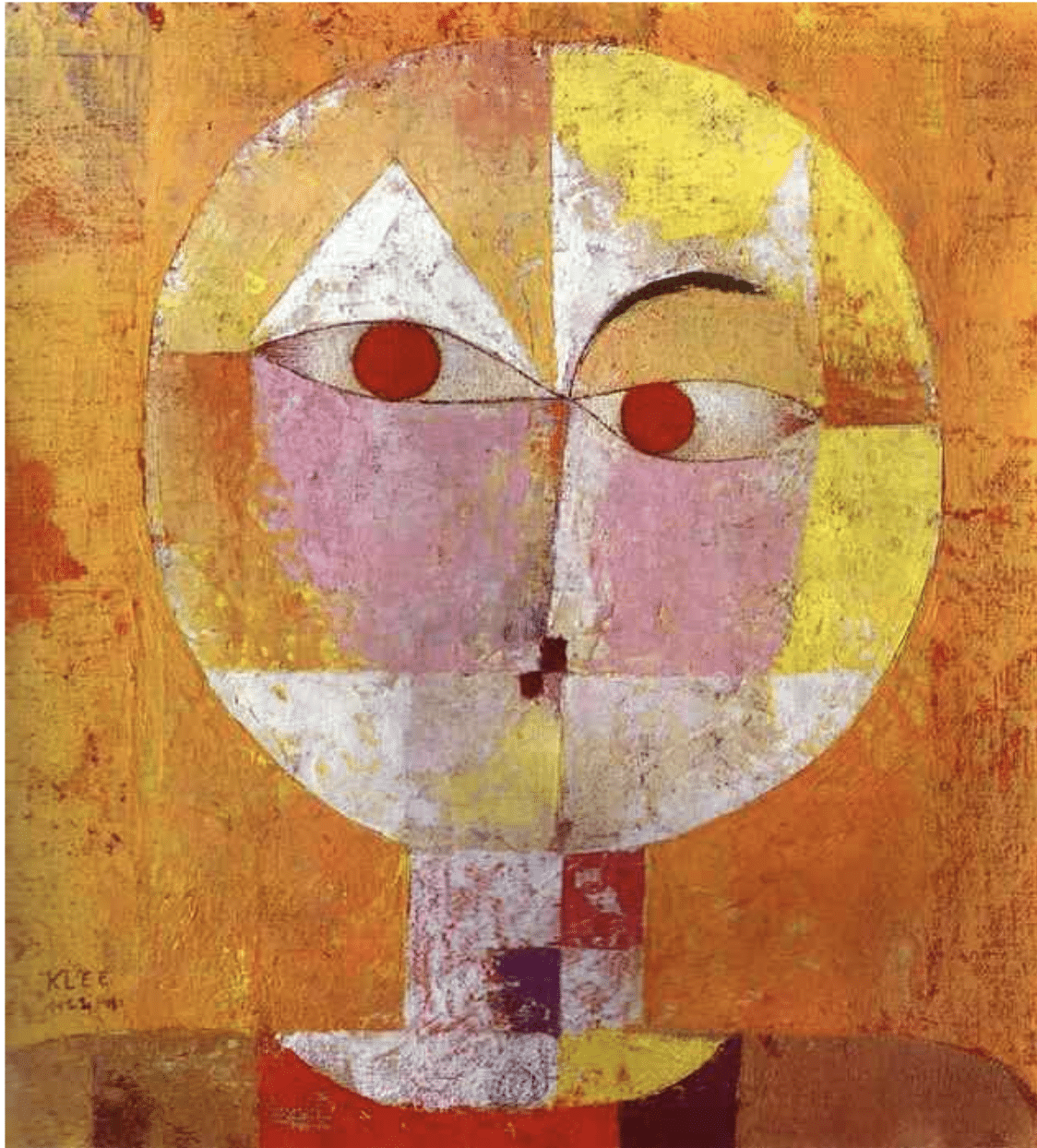

Paul Klee, Senecio,

- “When looking at any significant work of art, remember that a more significant one probably has had to be sacrificed.”

What makes a work of art “significant”? Klee would perhaps insist that the artist should reach for something Beyond, something greater than the sum of the parts. “In the final analysis,” he said, “a drawing simply is no longer a drawing, no matter how self-sufficient its execution may be. It is a symbol, and the more profoundly the imaginary lines of projection meet higher dimensions, the better.” Paintings point beyond themselves, to the mysteries of the imagination and the cosmos. With such “significant” aspirations, even Paul Klee must have felt at times what so many artists feel about even their best work – because, of course, it is of this earth, it can never match the intangible Ideal that the artist can sense and envision.

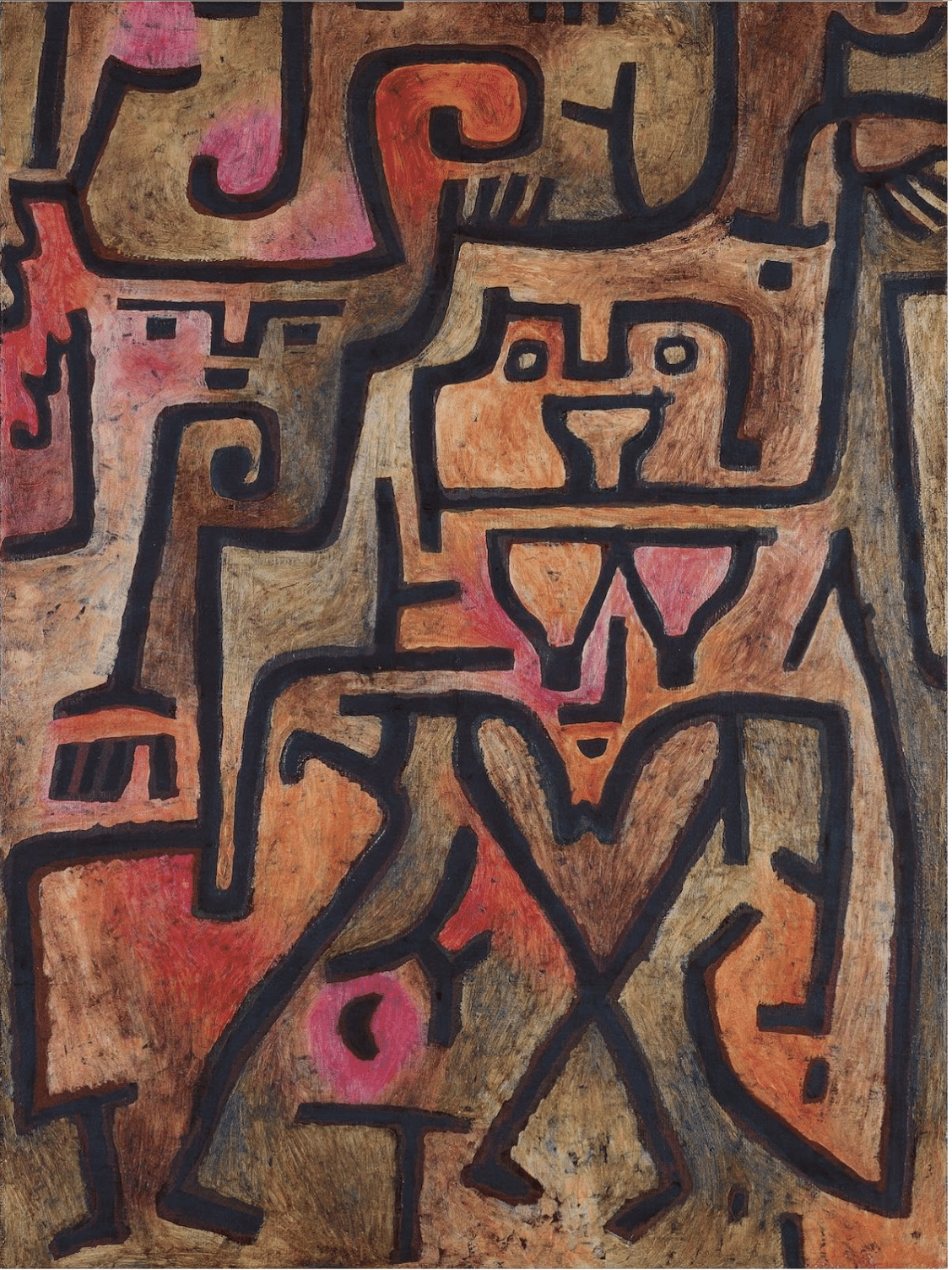

Paul Klee, Forest Witches, 1937

Why not browse some comprehensive instructional videos more inspiration on composition and design?