John Szartowski was the curator of the New York Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) from 1962 to 1991. It could be said that Szarkowski was visionary in elevating photography to a different level by changing the perspective of how photography was then viewed – as basic documentary medium to that to be viewed as a form of artistic expression. He promoted photographers who produced original and radical work such as Diane Arbus, Gary Winogrand, and Lee Friedlander demonstrated in the 1967 exhibition of their work titled ‘New Documents’ which showed their interpretation of the documentary genre. Perhaps his bravest decision was to give Eggleston a solo exhibition of his colour prints at MoMa in 1976 (William Eggleston’s Guide), a time when colour images were used for advertising, postcards and the like and were not in any way seen as comparable to black and white and definitely not as an expression of art.

This book has the same title as the previously reviewed book by Michael Freeman, both books’ purpose was to show what makes a good photograph. Freeman’s book took on a more basic and academic level and explains the various compositional parts that when combined in differing permutations produce good photographs.

John Szarkowski’s book is essentially about encapsulating what photography is all about. He shows how the evolution of the medium developed progressively because of it’s accessibility to the masses, you didn’t necessarily have to be a talented artist to produce a successful outcome. Szarkowski uses both snapshots and images created by famous photographers and unknown practitioners to provide strong justification of this view.

“The vision they share belongs to no school or aesthetic theory, but to photography itself. The character of this vision was discovered by photographers at work, as their awareness of photography grew” (Szarkowski, 1966)

As a skeletal structure to defining photography he sections the book by using five issues that all photographers would have had to address in some way to produce their images:

The Thing Itself – Photography deals with “the actual”, it shows reality and is impartial “for though the lens draws the subject, the photographer defines it” (Szartowski, 1966).

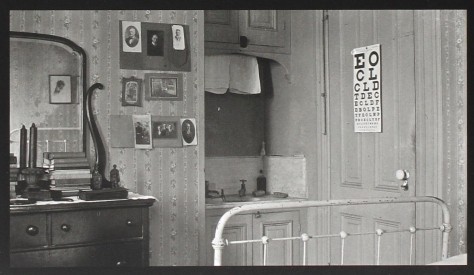

The first two images in this section are ideal examples:

Lee Friedlander: Untitled 1962

The Detail – The difficulty of how photography can be used to tell a story, whereas a painter could effectively manufacture a battle scene for example, the photographer had to break the scene down into a more symbolic form ” Intuitively, he sought and found the significant detail . His work, incapable of narrative, turned towards symbol” (Szartowski, 1966).

War photography is an obvious subject and there is no better example to symbollically show narrative as Roger Fenton’s 1855 photo ‘The Shadow of the Valley of Death‘ from the Crimean war. The symbolic nature of this image could be said in some ways to have been a victim of circumstance in that Fenton used a large format glass plate camera which needed 20 seconds for an exposure so photographing actual battle scenes would have not been possible, therefore he had to use other subject matter to represent the narrative.

Another photo that has immediately evident narrative is Declan Haun’s Justice – look at it no further explanation needed.

The Frame – Defines what content is included in the image, the intent can be driven by what content is framed and that which is excluded. “This frame is the beginning of his picture geometry. It is to the photograph as the cushion is to the billiard table” (Szartowski, 1966).

A classic Elliot Erwitt image that is a great example of Erwitt’s humour, is produced by the framing of this photograph of Yale’s Oldest Living Student. All the expected well known photpgraphers have great examples of this such as Paul Strand, Andre Kertesz & Albert Renger-Patzsch use framing to great effect. Perhaps the best example is that of an image by Jacque Henri-Lartigue – Simon Roussel on the beach, the framing is subtle but produces a composition that could easily be mistaken for a painting. It is a typical example of showing how framing help to produce a distinctive style.

Time – One of the basic reasons for taking any photo is to record and/or preserve time. There were also so many technical variations of taking the photo that gave photographers a vast subject matter. The most obvious of these was the work produced by Eadweard Muybridge sequence of image that proved when a horse trotted it did indeed have all of its hooves off the ground, it essentially a study in motion. Other examples use blurring of the subject e.g. Otto Steinart’s A pedestrian or using multiple exposures to give an impression of movement, Harry Callahan (Detroit) was well known for these types of photos. The most simple yet original example of time was that taken by Robert Doisneau which shows a group photo with human presence and what is left after everyone’s gone.

Vantage Point – Another way to change the composition and impact of an image was to move the camera, this would have similar affect as to what to frame in the shot. Moving to a different viewpoint did indeed change the ‘viewpoint’. “He [the photographer] discovered that his pictures could reveal not only the clarity but the obscurity of things, and that these mysterious and evasive images could also, in their own terms, seem ordered and meaningful” (Szartowski, 1966).

Irving Penn’s Woman in bed by suggesting the woman’s form by showing her torso and legs as an outline, merging them all in with the bed, by using the view from above turns what would be an ordinary and uninteresting image into one that adds subtlety in showing the beauty of a woman’s shape and form. Another unusual yet striking image is one by Bill Brandt – No.43 from perspective of nudes which just by the viewing angle and framing changes what could have been a portrait or landscape image into one of abstraction and realism.

Unsurprisingly this book does not have much in the way of text, there is an excellent introduction by Szartowski, (he also wrote an superb explanatory introduction to ‘William Eggleston’s Guide’ to clarify some context around the ‘controversial’ photos that Eggleston produced for his seminal 1976 exhibition.

The simple structure of the book built around the five key addressable components that every photographer has to make decisions on inclusion in confirming what the final image will look like and what intent it will portray, this helps makes photography more understandable and opens up interpretation of an image that many viewers maybe would have missed on first viewing.

Szartowski was indeed a visionary and can be viewed as one of the most important figures in the evolution of photography.

Bibliography

Szarkowski, J. (1966). The photographer’s eye. 1st ed. New York: Museum of Modern Art; distributed by Doubleday, Garden City, N.Y.