Georgia O'Keeffe's Lost Paradise

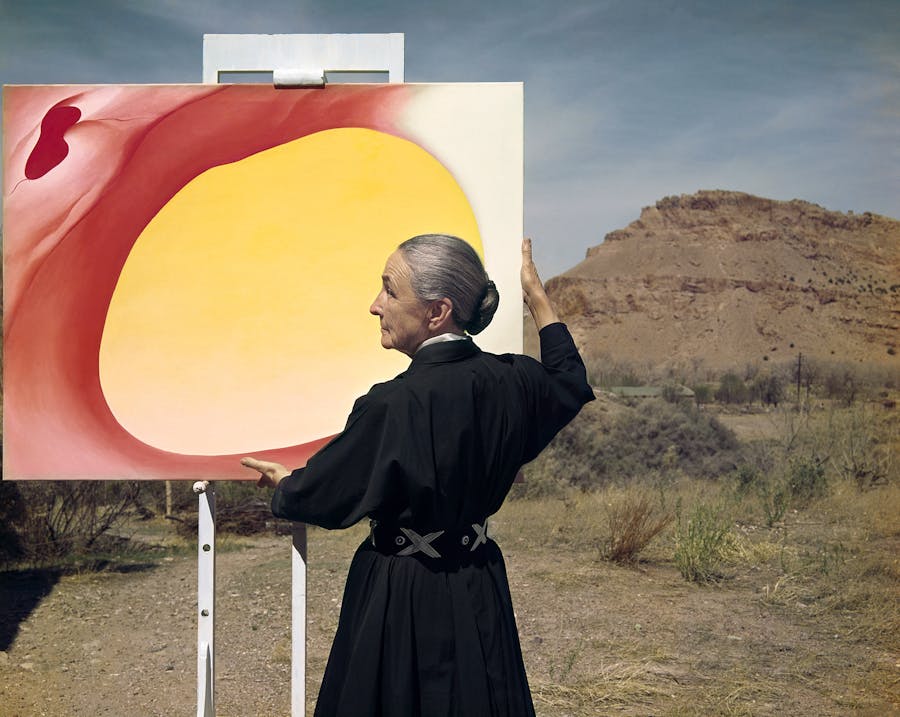

Known to the general public for her colorful and close-up floral paintings, Georgia O’Keeffe was one of the most important American artists of the 20th century. She found her place in the world on a ranch in New Mexico, when she left her husband in search of herself.

Born in 1887 on a farm near Sun Prairie in Wisconsin, Georgia O’Keeffe spent most of her life in New Mexico, the place that was undoubtedly her home even though she was not a native. After studying at the Art Institute of Chicago and the Art Students League, she met Alfred Stieglitz in 1916, an established photographer who headed the movement of the Photo Secession and owned 291 Gallery on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. O’Keeffe’s close friend Anita was the one to show a series of O’Keeffe’s charcoals to Alfred, who exclaimed, "At last, a woman on paper!"

Stieglitz, 23 years O’Keeffe’s senior and already married, was bewitched. Georgia became his inspirational muse, and the two eventually married. She was the object of his obsession, and between 1918 and 1925 he photographed her almost continuously, creating a rich portfolio of works. "I can see myself [in the photos taken by Stieglitz] and this helps me to understand what I mean in painting," O'Keeffe wrote.

Related: Georgia O’Keeffe’s Flower Power

But soon Stieglitz’s pressures and expectations became overbearing, and O’Keeffe felt oppressed by the imposing figure of her charismatic and narcissistic husband. Their relationship became increasingly turbulent, and she felt a desperate need to go in search of herself, to find new sources of inspiration. In New Mexico she identified the antidote to Stieglitz's glittering New York.

Related: 10 Artist Couples You Should Know

"You mean so much to me that you shouldn't get close, being close to me would bring you darkness instead of light, and it's the eternal light that you should live," Alfred wrote in a letter shortly before he left. The landscape of New Mexico, simple and pure, with warm and exotic colors proved to be exactly what O’Keeffe was craving.

Separated by land but never far from each others’ thoughts, the two exchanged over 25,000 letters, some over forty pages long. Collected by Sarah Greenough in the volume My Faraway One: Selected Letters of Georgia O'Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz: Volume One, 1915-1933, the letters that tell of a passionate love that was overwhelming yet unsustainable in person, leading them to pursue intimacy at a distance.

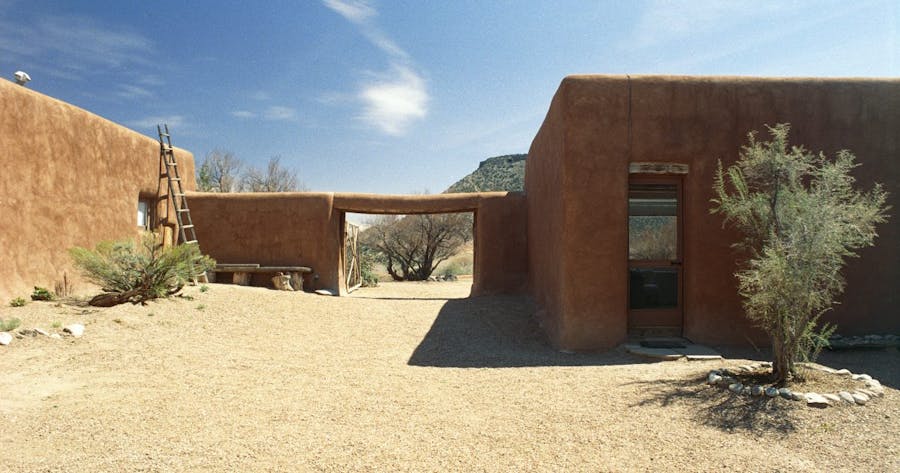

In 1940, Georgia acquired a summer home known as Rancho de los Burros located on seven of the Ghost Ranch's more than 21,000 acres. She purchased her small plot of Ghost Ranch land from Arthur Pack, one of the Ranch's then owners. Ghost Ranch is about fifteen miles northwest of the village of Abiquiú, where, in 1945, O'Keeffe purchased a separate property from the Catholic Archdiocese which she used as a home and studio.

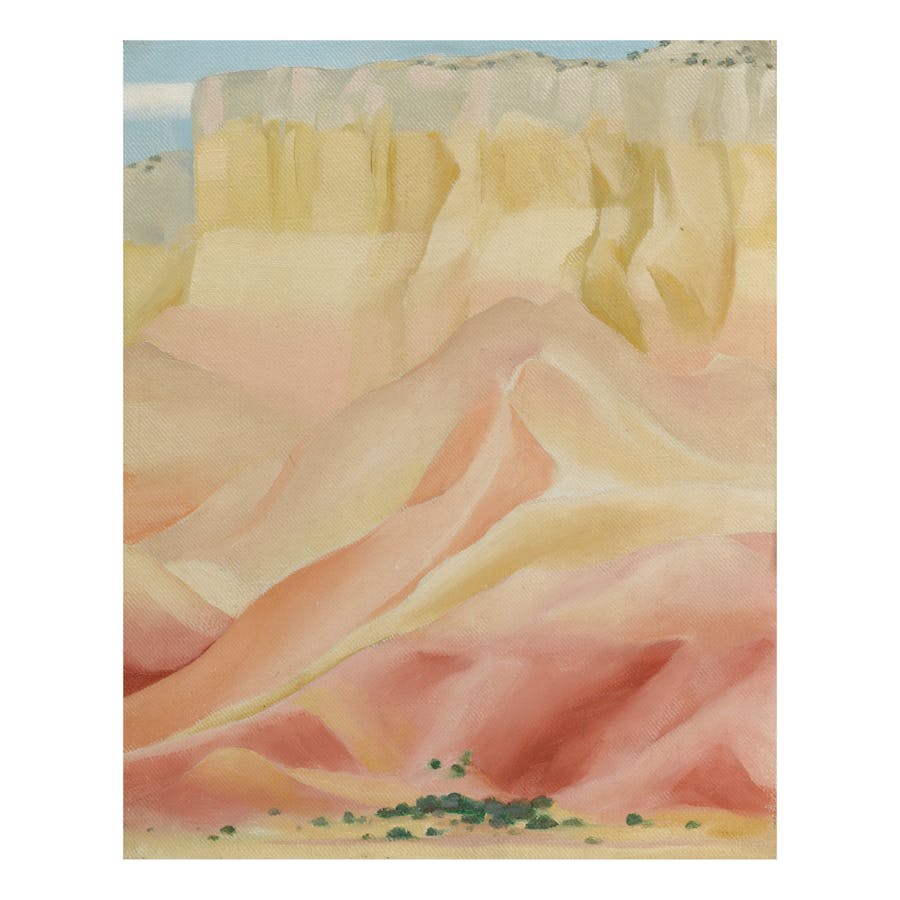

"I wish you could see what I see outside my window," she wrote to artist Arthur Dove, "a cliff of pink and yellow earth in the north... some pink and purple hills in front and thin opaque cedars, a feeling of greatness, it's really a beautiful world here." My Backyard, painted in 1945, is a visual translation of the words written to Dove. This extraordinary painting was sold by Sotheby's on November 19, 2019 at the ‘American Art’ auction for $1,340,000.

Related: The 15 Most Expensive Female Artists

O’Keeffe’s paintings are desert poems, wrapped in a timeless lyricism. Making progressive simplifications to the nuances of reality, O’Keeffe worked on the subject until it was reduced to its essence, to its archetypal idea, without ever renouncing the integrity of the figurative subject. She did not want to represent the appearances of the world in their transient essence, but rather sought the true character of things. Hers are meditation paintings. She did not paint merely immediate impressions, but feelings, a quality that develops through time and reflection.

Ghost Ranch became the link between two opposing worlds: that of scientists working on creating the atomic bomb for the Manhattan Project, and that of O’Keeffe’s reflective artistry. Located about 55 miles south of Ghost Ranch, Los Alamos was the site of the secret laboratory where the first nuclear weapons were designed and built during the 1940s. On July 16, 1945 at 5:29 am, a dazzling golden and violet light that no human had ever seen before resulted from the shockwave of the first nuclear test, which took place at Trinity, located in the Jornado del Muerto desert in southern New Mexico.

"It was a moving and solemn show, something that made me think that life would never be the same," wrote J. Robert Oppenheimer. It was then that O’Keeffe discovered the true identity of the people with whom she had been sharing her ranch: Oppenheimer, Niels Bohr and Enrico Fermi.

Related: Yayoi Kusama: The Queen of Cool

Not even a year later, O’Keeffe's anxiety was deepened by the loss of Stieglitz. Only her house amidst mountainous desert landscape could give her the peace she dreamed of. She spent her days painting and collecting stone cow skulls during her long walks in the desert, objects that recur many times in her works. In the mid-1970s, macular degeneration began to compromise her vision. Like Monet with his Cathedrals, O'Keeffe too returned to painting subjects dear to her, such as Untitled (City Night), a work that revisits the forms of her 1926 painting City Night. In the early 1980s, she began expanding to a new medium, clay, aided by the young ceramist Juan Hamilton. Guided by her hands more than her sight, O’Keeffe devoted herself to sculpture until her death in 1986 at the age of 99.

Article by Giulia Mastropietro