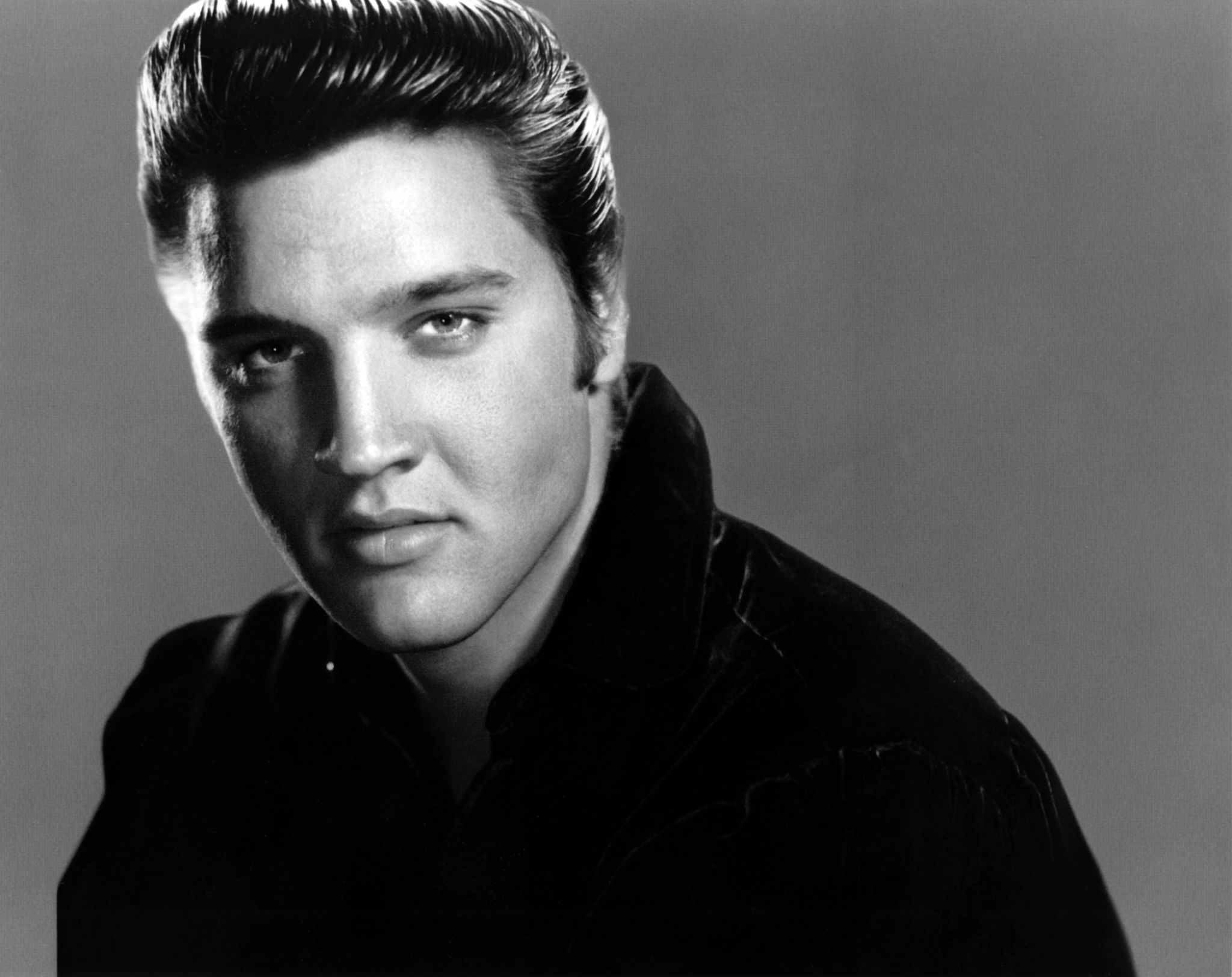

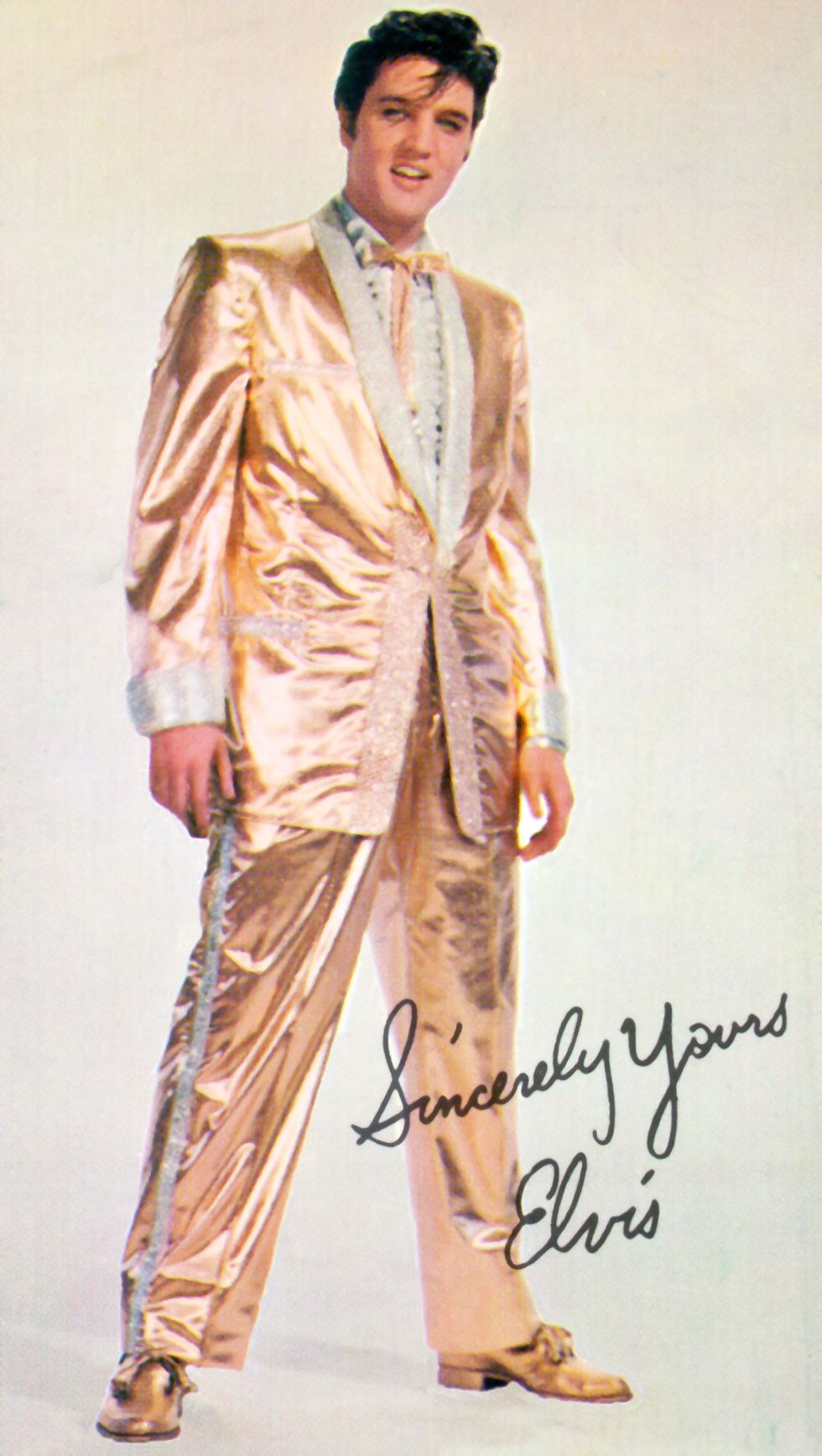

In 1957, he looked truly like a god. Breathtakingly — almost indecently — handsome. There in his $10,000 gold lamé suit, the chiselled face, the saturnine eyes, the greased-back pompadour hair, a cowlick falling over his forehead, the curl of the lip, arrogant and amused.

The suit was made by Nudie’s Rodeo Tailors of Hollywood at the behest of Elvis’s manager Colonel Tom Parker, who wanted a golden suit for his Golden Boy — “boy”, in the proprietorial sense being how the Colonel would often refer to his charge, gold being the currency that Elvis was minting, not least for the Colonel, at the height of his fame.

The “$10,000” price tag, like most things to do with the Colonel, was an exaggeration, showmanship; the actual bill of sale was for $2,500. Elvis first wore the suit at a performance at Chicago’s International Amphitheatre in March 1957. In the space of three years, he had recorded eight number-one records, among them “Heartbreak Hotel”, “Hound Dog”, “Love Me Tender” and “All Shook Up”. He was 22 years old, already the hottest property in American music, soon to be the most famous singer in the world. Twenty years later, he would be dead.

Elvis was America writ large, in all its greatness and tawdriness, its promise and its disappointments, its fractured history and its promise of redemption. “The pure products of America go crazy,” wrote the poet and writer William Carlos Williams, and none went crazier than Elvis, his heart giving out on 16th August 1977 as he sat on his lavatory in his Graceland mansion, bloated and broken and bemused by the ingestion of some 10,000 pills in the last year of his life. He was 42.

Medical examiners found that he had traces of 14 drugs in his system at the time of his death, 10 of which were present in significant quantities, including codeine, morphine, diazepam, pentobarbital and ethinamate — drugs most commonly prescribed for anxiety and insomnia.

In a way, it’s easy to believe that Elvis now is bigger than he ever was when he was alive. He has become a myth. A morality tale. His music is lodged forever in the collective memory. His films are playing on an endless loop somewhere on TV.

His life has been dissected, pored over, analysed and referenced countless times in books and articles, such as this one, studied in university courses, endlessly memorialised in films, as souvenirs and in the caricatures of Elvis impersonators. Along with those two other defining figures of his generation, Marilyn Monroe and James Dean — the tragic American trilogy — his image is iconic.

In 2008, an Andy Warhol silk-screen, Eight Elvises, was sold by the Italian art collector Annibale Berlingieri in a private sale for $100m to an unidentified buyer, thought to be the Qatari royal family. In 2014, another Warhol painting, Triple Elvis, sold for nearly $82m at an auction at Christie’s in New York. In the years since his death, the character of Elvis has featured in some 31 feature films, played by actors including Kurt Russell, Harvey Keitel and Don Johnson. According to the film critic John Beifuss, since 1957 there has been a minimum of 400 movies that contain some allusion to Elvis, 18 a year since 1998. In June, the Australian director Baz Luhrmann, of Moulin Rouge! and The Great Gatsby notoriety, will add to the list with a new film, starring Tom Hanks as the Colonel and a newcomer, Austin Butler, as Elvis.

The appeal to film-makers like Luhrmann is not difficult to understand: Elvis is estimated to be the best-selling solo music artist of all time, with sales of more than 500m records. Only the Beatles, with 600m, have sold more. Since his death, he has had 48 top-50 hits in the UK, including five number ones. You hear his records everywhere, on the radio, in adverts. Recently, walking out of the Francis Bacon exhibition at London’s Royal Academy, I was struck to hear “Suspicious Minds” being played in the gift shop as people browsed the postcards, posters and catalogues illustrated with Bacon’s hellish studies of the bestiality of man. The song sounded like a memento mori. All of us will eventually slip this mortal coil, but the greatest of us may attain a kind of immortality.

THE CREATION STORY

There were people named Elvis before him, but nobody could be named Elvis after him without it being an act of acknowledgement and homage. It was his and no-one else’s.

He was born in the city of Tupelo, in one of the poorest counties in Mississippi — a place of cotton fields and mills, limited job security and hand-to-mouth subsistence.

His father Vernon was a sharecropper and sometime truck driver; his mother Gladys a seamstress, a woman who, in Southern parlance, “didn’t meet a stranger” — a font of warmth and good heart. Elvis idolised her.

Gladys was 21 and Vernon was 17 when they married — but they both lied about their ages. Gladys said she was 19 and Vernon said he was 22. Elvis was born less than two years later on 8 January, 1935, the firstborn of identical twins. His brother Jesse was stillborn. When Elvis was 13, Vernon moved the family 100 miles to Memphis, Tennessee, in search of work. “We were broke, man, broke,” Elvis would later recall, “and we left Tupelo overnight.”

He sucked up music from the radio and jukebox; close harmony singing by The Ink Spots; the Southern gospel quartet the Blackwood Brothers and the R&B singer Roy Brown, his particular favourite, whose smooth vocal style would be a formative influence and whose 1947 R&B hit “Good Rockin’ Tonight” Elvis would cover for his second Sun single in 1954.

At Humes High School, he grew his hair long and slicked back when everybody else had crewcuts and dressed in pink and black. “He was just different,” his school friend Red West would remember. “It gave people something to do, to bother him.”

He spent whatever he could afford at Lansky Bros on Beale Street, Memphis’s black Broadway; — he’d buy spiffy sports coats and shirts in neon blues and get-down pinks that were worn by bluesmen and street cats. “I put Elvis in his first suit,” the owner Bernard Lansky would later remember, “and I put him in his last.”

Elvis took a job driving a truck for a local electrics supply company. Nobody thought he’d ever amount to anything.

In the summer of 1953, he walked into a local studio, Memphis Recording Service, intending to make a recording as a birthday present for his mother. The studio was owned by Sam Phillips. He was a pioneering figure, with a particularly enlightened view of race relations — a prickly subject in Memphis in the 1950s. He recorded all sorts of music in his studio, but had a particular love for blues and R&B. He’d made recordings with artists such as Howlin’ Wolf, BB King and Junior Parker, which he’d leased to record labels in Chicago and Los Angeles before setting up his own label, Sun. At a time when music was rigidly divided by race, Phillips is credited with perhaps the most prescient statement in the history of rock ’n’ roll: “If I could find a white man who had the Negro sound and the Negro feel, I could make a billion dollars.”

It sounds too pat to be true, but Phillips certainly realised that black music was popular with many young whites. It was the artists’ race that prevented their music reaching a wider audience.

Elvis paid four dollars to record two songs on that afternoon he visited Memphis Recording Service — “My Happiness”, which had been a hit for The Ink Spots, and a lachrymose ballad, “That’s When Your Heartaches Begin”. After he’d gone, a note was appended to his name: “Good ballad singer. Hold.”

A few months later, he returned to the studio to make another four-dollar recording, with his eyes now set on a singing career. Phillips was sufficiently impressed to invite him back, this time accompanied by two local musicians, Scotty Moore and Bill Black. They worked on a couple of ballads and country songs, and at the end of the session, Elvis started vamping on “That’s All Right”, a country blues song written and originally recorded by Arthur Crudup in 1946.

With a bluegrass song, “Blue Moon of Kentucky” as the B-side, the record was released on Sun Records in 1954. Sam Phillips took the first pressing to a local R&B radio station and a white DJ named Dewey Phillips. After one play, the switchboard lit up. Dewey called Elvis to interview him on air. “Mr Phillips, I don’t know anything about being interviewed,” Elvis said. “Just don’t say nothing dirty,” Dewey replied.

Dewey asked where Elvis had gone to high school. “Humes,” Elvis replied. “I wanted to get that out,” Dewey later recalled, “because a lot of people listening had thought he was coloured.”

“He has a white voice, sings with a Negro rhythm, which borrows in mood and emphasis from country styles,” a Memphis paper noted. But the record hardly set the world alight, failing to make the national charts. It was his performances, onstage and on national television, that would ignite the Elvis phenomenon.

There is film of Elvis appearing on stage in his hometown of Tupelo in 1956, an outdoor, afternoon show. He is dressed all in black, an acoustic guitar slung over his shoulder, singing “Heartbreak Hotel”, bumping and grinding as he slurs the words like a lascivious kiss — “I’m ever so lonely, babeee” — executing a series of rapid pelvic thrusts when Scotty Moore picks up the guitar solo, the girls crowded at the lip of the stage, arms outstretched in unbridled lust, while three cops in peaked caps look on, bemused.

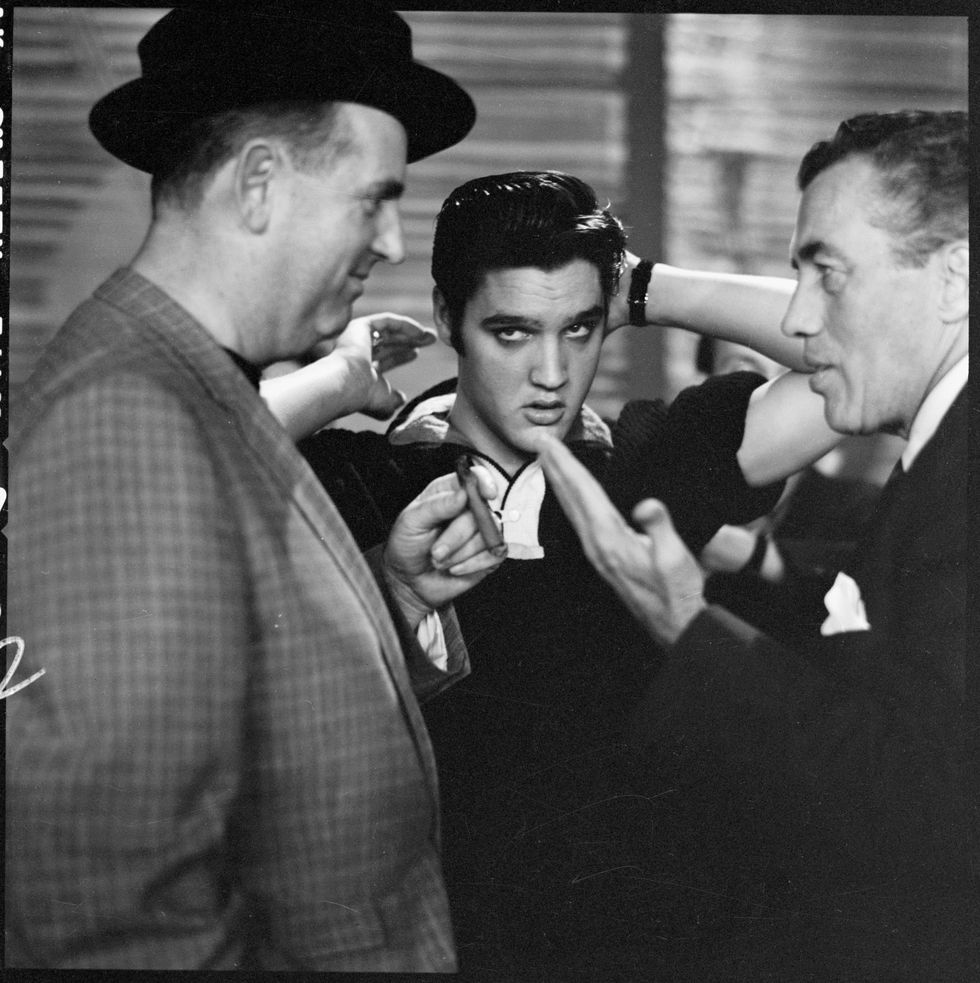

Girls had swooned and screamed for Frank Sinatra in the 1940s. “Police and ambulances had to be summoned”, read a report in the New Republic of one of Sinatra’s New York shows. But as puzzled as commentators — and psychologists — might have been by the new phenomenon of “fandom”, Sinatra did not threaten the natural order of things. Elvis blew that natural order apart. Sex, race, the perils of juvenile delinquency — Marlon Brando’s biker movie The Wild One had been released a year before “That’s All Right” — the cordite whiff of moral bankruptcy… he was the blue touchpaper, the match and the explosion. Parents fretted and gimcrack politicians, Baptist ministers, tub-thumping opportunists of every persuasion railed against the pernicious influence of “n****r music” on white teenagers succumbing to hysteria and lust. After Elvis, pop music would never be the same again.

COLONEL TOM PARKER

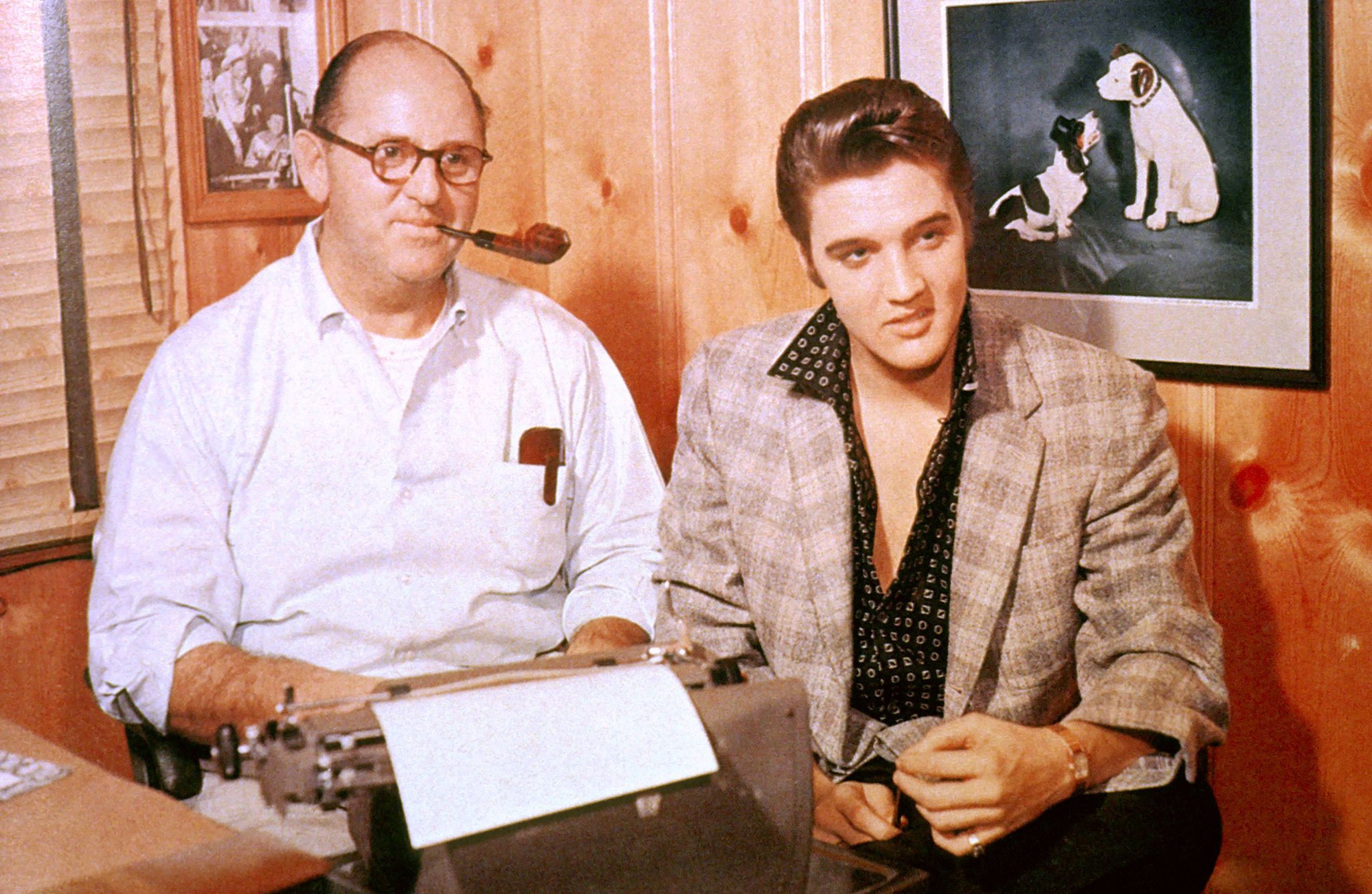

It was both a stroke of good fortune, and a cruel twist of fate, that Elvis should have got involved with Colonel Parker: a carney, a huckster — shrewd, greedy and callous, the man who would make Elvis a star and, eventually, be a major figure in his destruction.

Of course, he wasn’t really a colonel at all. His name was not Tom Parker. Nor, as he claimed, was he born in West Virginia.

He was actually born Andreas Cornelis van Kuijk in Holland, entering the United States illegally when he was 20 — a deception that would have been revealed had he ever allowed Elvis to realise his dream of coming to England.

He worked as a barker and sideshow pedlar in a travelling carnival. One stunt was to spray sparrows yellow and sell them as canaries; another he borrowed from the showman PT Barnum. Barnum had trouble getting his customers to leave his exhibits, so he put up a sign on the door saying, “Egress this way”, charging an extra nickel, reasoning that most people would not be aware that egress is another word for exit.

Parker became a well-known figure in the South. In 1948, the governor of Louisiana gave him the honorary title of Colonel, and from then on, he instructed everyone to address him as such. By then, he had left the carnival behind and moved into managing country-and-western artists and promoting country music shows.

When he saw the effect that Elvis had on his audiences, he offered Sam Phillips $35,000 to buy Elvis’s recording contract. Parker himself did not have the money, but he persuaded a major label, RCA, to front the cash, at the same time becoming Elvis’s manager. It was a handshake deal. The Colonel took 50 per cent.

Parker cared little for Elvis’s music; he saw him as a commodity, a paycheck — and he was right. At the early Elvis shows, he would move among the crowd, cigar between his teeth, selling autographed pictures for 50 cents each. Playing on the controversy surrounding Elvis, badges would also be on sale saying “I love Elvis” and “I hate Elvis” — both produced by Parker.

As a carnie, Parker would draw people to his sideshow promising “dancing chickens”; he’d throw feed on a hot plate and the chickens would jump around. Elvis was to become his dancing chicken.

No matter how detrimental to his long-term career, Elvis would bow to his every decision. The Colonel had brought him riches and recognition beyond his wildest dreams — and Elvis would forever be bound by gratitude and obeisance.

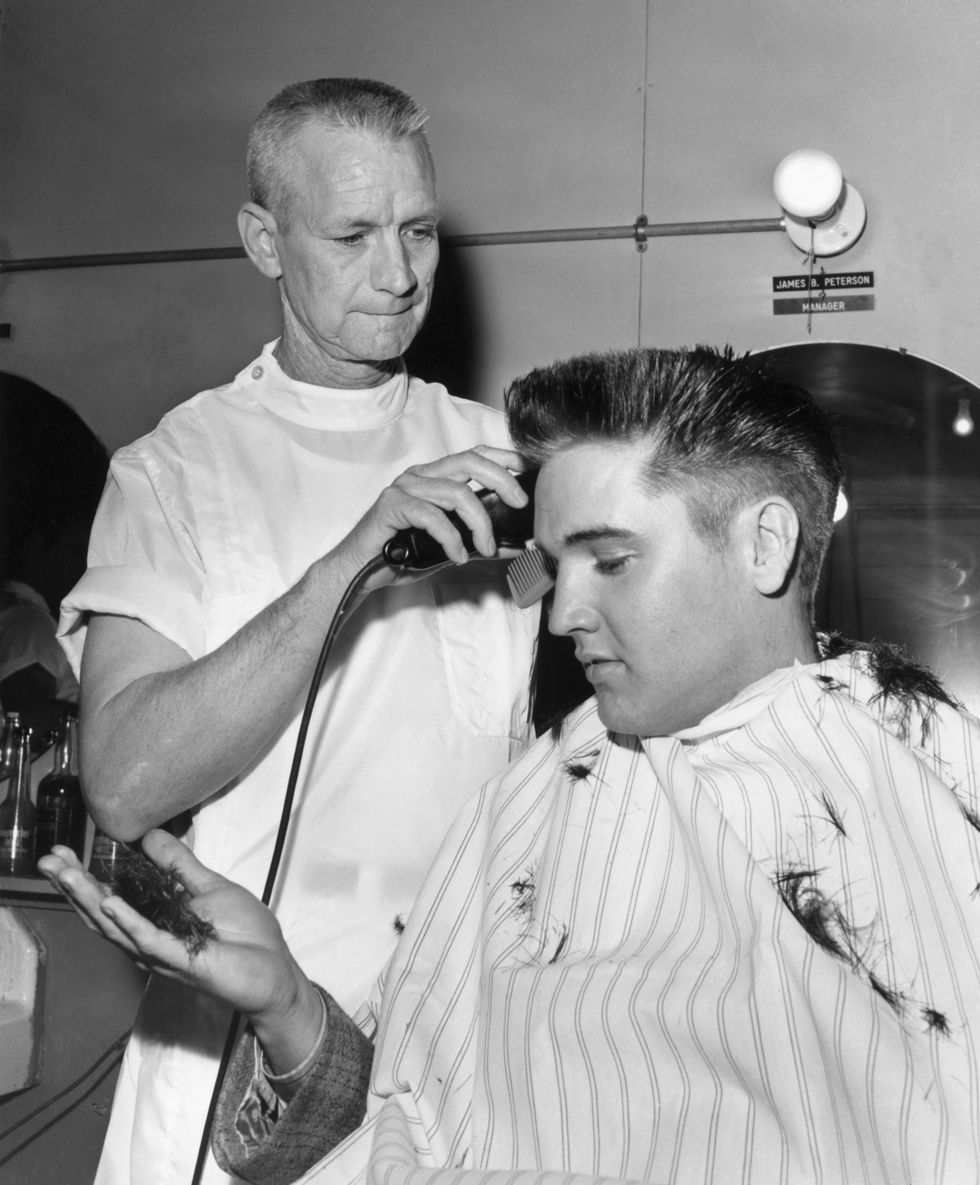

In 1958, at the height of his popularity, Elvis was drafted into the US army. He spent two years stationed in Germany, returning with a new haircut and a new career. He had appeared in four films before going into the army, including Jailhouse Rock and King Creole, and he harboured a desire to follow in the footsteps of his role models James Dean and Marlon Brando as an actor. Parker duly obliged, striking a movie deal whereby Elvis — and therefore the Colonel — got a piece of the movie money up front. Hal Kanter, who directed two Elvis movies, Loving You and Blue Hawaii, would describe Parker as “one of the sharpest con-men I’ve ever come across”.

But Elvis’s ambition to be a serious actor was thwarted by the pablum he was contractually obliged to appear in. The 27 films he made in the 1960s were, for the most part, formulaic musical comedies: vehicles for increasingly mediocre songs that drained him of any musical credibility.

It was not until 1968 that he would resurrect his musical career, with the live TV special, simply called Elvis, leading the following year to him recording From Elvis in Memphis, the sessions of which would produce two of his most timeless hits, “In The Ghetto” and “Suspicious Minds”.

He was untouchable now, the Colonel his gatekeeper, secluded in his own world with his coterie of boyhood friends and hangers-on: “the Memphis Mafia”, Southern boys like Elvis, who liked riding motorcycles, big cars, guns and chasing girls (not, in Elvis’s case, that much chasing was required). “He had created his own world. He had to,” as the singer Johnny Rivers put it. “There was nothing else for him to do.”

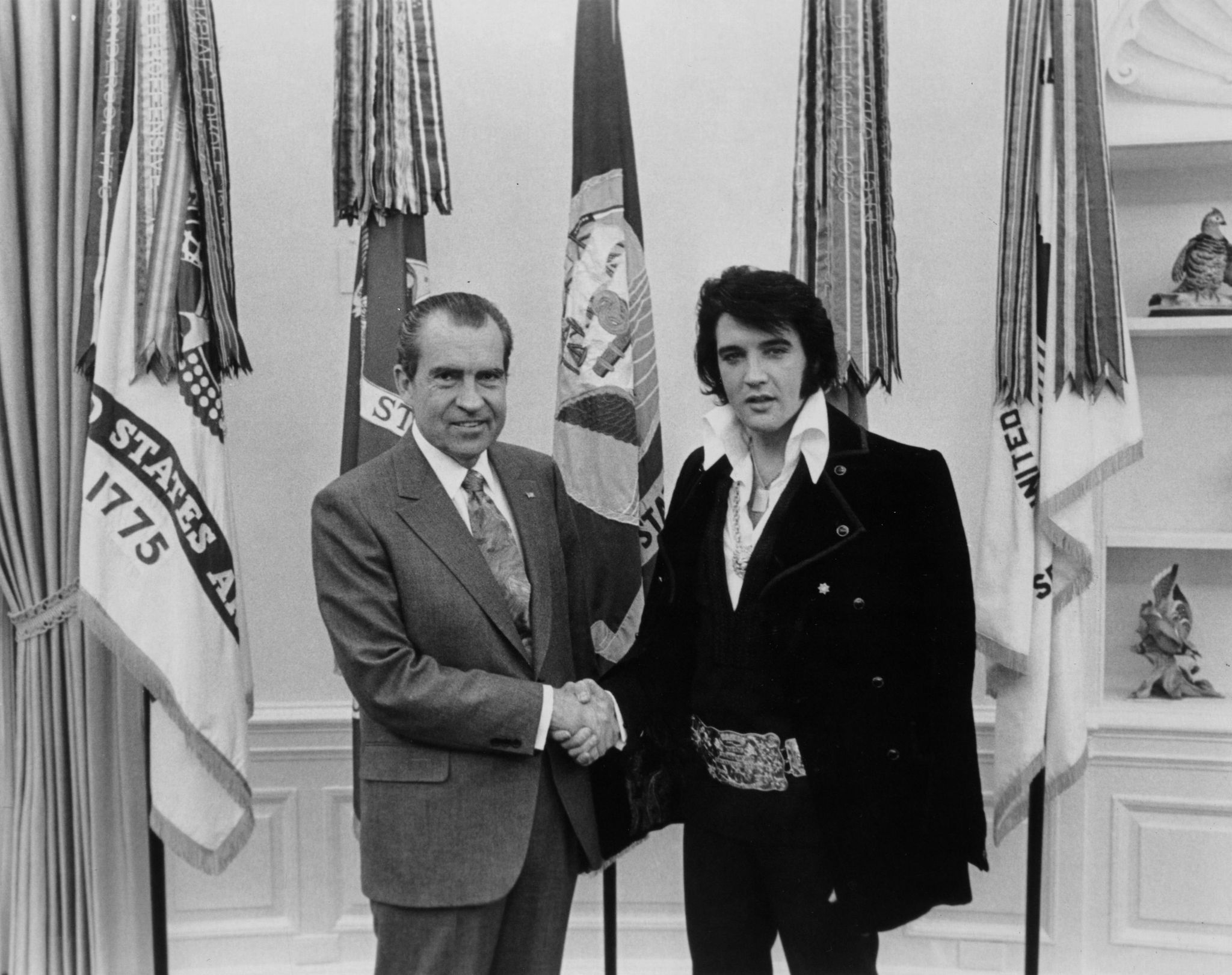

The cultural rebellion brewing beyond the closed gates of his mansions in Memphis and Bel Air passed him by. He was a patriot, a proud American, invited to the White House in 1970 by Richard Nixon who presented him, with no discernible trace of irony, with an honorary Bureau of Narcotics badge. Elvis presented Nixon with a mounted Colt 45.

In Germany, Elvis had met Priscilla Beaulieu, the 14-year-old stepdaughter of a US Air Force officer stationed there. Elvis was besotted and, in 1963, Priscilla moved to Memphis, at first living with Elvis’s parents and then, chastely, in her own quarters at Graceland, while Elvis was in Los Angeles making films and having an affair with the Swedish-American actress Ann-Margret.

In 1967, he married Priscilla in a ceremony arranged by the Colonel at the Aladdin hotel in Las Vegas, where the Colonel thought the roulette tables were the luckiest in town. According to Albert Goldman’s scurrilous biography, the marriage was consummated on their wedding night, sexual relations ceasing shortly afterwards.

For the next 10 years, Elvis would embark on an intense regime of live performances, at amphitheatres and concert-halls across America, but mostly in Las Vegas — where the Colonel liked to be and the paychecks were largest.

“Elvis has left the building” is what they would announce as he was hurried off stage, past the thrusting, pawing fans —not teenagers, but women of a certain age whose teenage lives had been ignited by the young god, once touched never forgotten, desperate for a glimpse, as their husbands retreated to the endless night of the gaming tables.

It was Vegas that would destroy him, the Colonel pressuring him to perform, right up to the moment when he was sick and bloated, his act a parody of what it had once been — the first Elvis impersonator, as someone once put it.

In 2007, covering the Los Angeles murder trial of Phil Spector — dubbed the “First Tycoon of Teen”, whose productions for the Crystals, the Ronettes and the Righteous Brothers had for a period in the early 1960s eclipsed Elvis’s sales — I would sometimes sit in the courtroom with the doyenne of American court-reporting, Linda Deutsch of the Associated Press, who had covered the trials of Charles Manson, OJ Simpson and Michael Jackson. Her passion was Elvis. She had seen him perform on a number of occasions in Las Vegas, and gave one of the best descriptions of the power of artistry I have ever heard: when he looked out into the audience, she said, it was as if he was looking directly into the eyes of every person there.

Spector had produced demos of songs recorded by Elvis, claimed to have worked on his first album coming out of the army — although that’s a matter of dispute — and idolised him, as every artist and producer of that era did.

Spector would sometimes travel to Las Vegas to see Elvis perform and would always go backstage after the show. Dan Kessel and his brother David were Spector’s constant sidekicks in the 1970s and joined him and his constant bodyguard George on one visit. “Elvis had the full Memphis Mafia. It was very intense,” Dan once told me, “the full Phil trip, and the full Elvis trip. They knew who each other were. They were like two panthers checking each other out. You could tell — mutual respect. It was definitely one of those moments.”

John Lennon would later confess the Beatles were “terrified” on the night in 1965 when the group made their way to Elvis’s Bel Air home for an audience with the King, negotiated by their manager Brian Epstein. Elvis’s career was at its lowest point in 10 years. He had not had a number-one single in America for three years. The Beatles had had 10. He was bemused by them; they were worshipful to the point of speechlessness. “It was a little bit awkward because they kept looking at him and not really saying anything,” Priscilla remembered. Finally, Elvis said, “Well, guys, if you’re going to just sit around staring at me, I might as well go to bed,” breaking the silence by picking up a bass guitar and playing along to the song on his jukebox, Charlie Rich’s “Mohair Sam”. They spent the next three hours jamming and talking about music. At the end of the evening, the Beatles floated the hope that Elvis would visit them where they were staying in Los Angeles. After they’d left, Elvis supposedly told one of his entourage, “I’m not going up there. I did my duty. I met them, and that’s it.”

Meeting Nixon five years later, Elvis would tell the President that the Beatles were “a real force for anti-American spirit”.

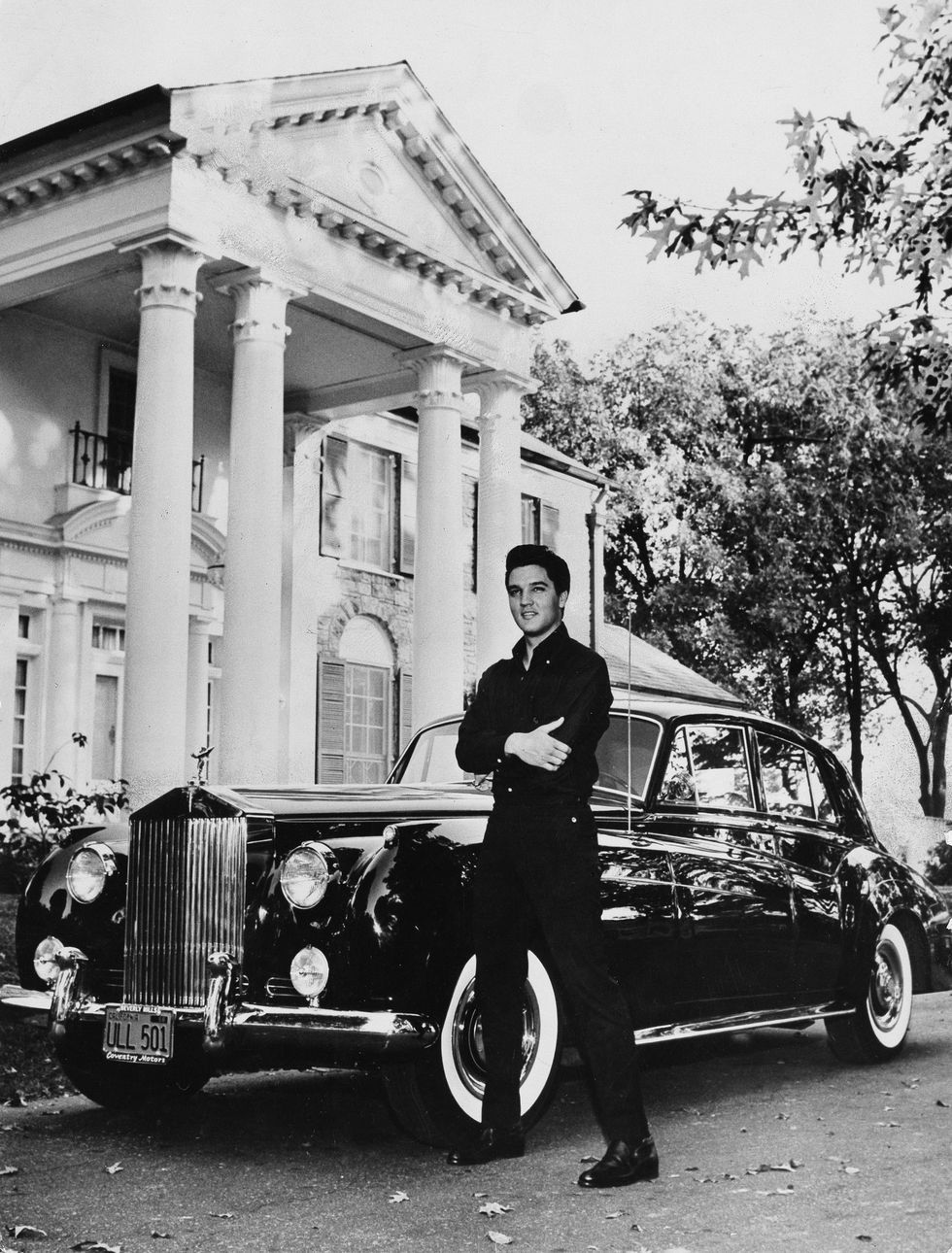

GOING TO GRACELAND

Given the choice of prime real estate his fortune would avail, it is curious that Elvis should have chosen to spend his days in a mock-colonial mansion perched on the crest of a hill offering a commanding view of a four-lane highway — today named in his honour, Elvis Presley Boulevard — and lined with neon-lit motels, fast-food outlets and car dealerships decked out in plastic bunting.

The environs of Graceland have been somewhat enlarged since Elvis’s death. The original 13-acre estate is now a sprawling complex spread across 120 acres, including its own shopping centre, 450-room resort hotel, car parks and a motor museum. More than 500,000 visitors make the pilgrimage each year.

I made my own journey some years ago. A small bus ferried visitors up the drive to the mansion itself, and we entered with the hushed reverence of visitors to the Sistine Chapel, except here was not symmetry, beauty and the spirit in flight, but heinous taste, berserk ostentation, the evidence of a soul unhinged. Bob Krasnow, a record executive, whose label Blue Thumb Records released records by Ike Turner, famously quipped after visiting Turner’s home that he “didn’t know it was possible to spend a million dollars in Woolworths”. Graceland proved it was possible to spend two million.

We trooped through through its fantasy rooms, admiring the carpeted walls and ceilings, the nitrous yellow bar-fittings and fake animal-skin furnishings, the security cameras in every room, linked to a central console so that Elvis could spy on his guests from the privacy of his bedroom — closed to the public “out of respect for Elvis”.

The “walk of fame” was clogged with the gold records and stage costumes, including the suit of gold lamé, retrieved in 1987 by Elvis Presley Enterprises at a cost of $2m dollars from Colonel Parker, among the estimated 35 tons of “stuff” that Parker had stored in four buildings in a Nashville suburb.

And there was Elvis’s collection of guns (his “favourite” was a turquoise-handled Colt 45) and his honorary sheriff’s badges. The tour guide, a matronly woman, stressed his respect for law and order, his philanthropy, his love for mother and country and his profound religiosity. “They called him the ‘King of Rock ’n’ Roll’”, she murmured, “but he would tell them, there is only one King, and that is Jesus Christ.”

I looked in vain for the evidence of his downfall: the selection of pill bottles, the framed doctor’s prescriptions, the symbolic plates heaped with artery-inflating junk food. But they were nowhere to be found.

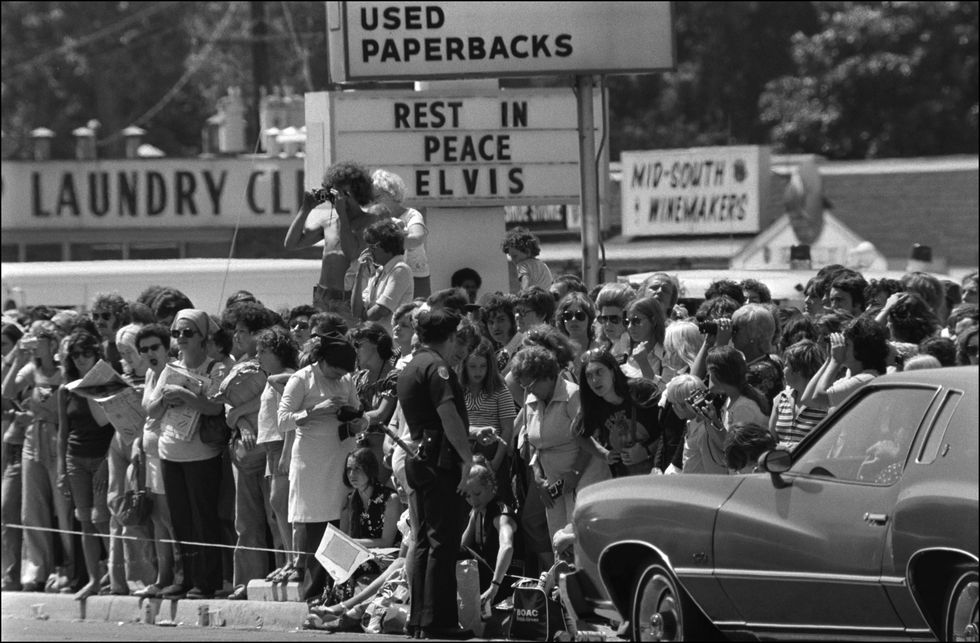

His funeral was held at Graceland, where thousands queued to see his open casket. Outside the gates, two people died when a car ran out of control. More than 80,000 people lined the processional route to the Forest Hill Cemetery in Memphis, where Elvis was entombed in the crypt at the Presley room. But after fans and souvenir-seekers had tampered with his grave, Elvis and his mother Gladys Presley were moved to their current resting place in the Memorial Gardens at Graceland, later to be joined there by his father Vernon.

At the graveside, scented with an abundance of floral tributes, women dabbed at their eyes with handkerchiefs and clutched at their husbands’ arms for support. A man whispered to me, “It’s like an anthropological study of how religions get started.”

But, of course, the religion had started on the day Elvis died. His miraculous resurrection has been witnessed in the years since, in supermarkets, gas stations and fast-food outlets. He was spotted appearing in the background of an airport scene in the 1990 film Home Alone and, famously, through a telescope lens, on the moon. A Bristol businessman, visiting Graceland, was astonished to hear Elvis addressing him from his tomb, saying, “I can’t stand tulips. Why did you bring me goddam tulips?”

His image has been kept alive by legions of imitators, most favouring the mid-period Vegas look of white jewel-encrusted jumpsuit and scimitar sideburns. Some years ago, on Elvis’s birthday, I made another pilgrimage, this time to the Graceland Palace, a Chinese restaurant on the Old Kent Road, where each night the owner Paul Chan — “the Chinese Elvis” — would burst out of the kitchen in full regalia and astonish customers digging into chow mein and sweet and sour pork by performing an energetic round of Elvis hits, culminating with “Are You Lonesome Tonight” — before departing to his second restaurant in Tunbridge Wells, where the show would be repeated.

Like holy relics, Elvis’s belongings have been traded at auctions and fairs. In 1994, more than 1,000 Elvis Presley items, including guitars, cars, macramé pot holders, a grey wool “Superfly” hat, and the record of his birth, acquired from the secretary of the doctor who brought him into the world, were auctioned in Las Vegas. Elvis’s navy blue denim swim trunks (size 38 waist) fetched $2,070; his pyjama bottoms went for $2,250 and his comb for $950.

Like pieces of the Cross, these relics are the currency of the faithful, from the authentic (the Dowager Duchess of Devonshire, improbably an ardent Elvis fan who visited Graceland three times, securing a piece of picket fence with a nail that may or may not have been knocked in by the King’s own hand), to the most gimcrack. Elvisly Yours is a mail-order business, which not only sells every imaginable merchandise from TCB medallions to Elvis toiletries sets, but also acts as a virtual chapel of prayer where worshippers can leave tributes and poems, like “Elvis, Take My Hand” by Diane Burgess:

When the darkness surrounds me

Elvis, take my hand

When I’m afraid and lonely,

Help me understand.

Stay by my side, Elvis,

Help me keep the burning candle alight.

Show me the path I have to take,

Lead me to all that’s right.

Watch over me, Elvis,

With all your love and care,

Give me a sign, Elvis,

So that I know that you’re there.

Elvis hear my plea,

Elvis hear my call,

I’m tired and I’m weary,

And I need you most of all.

Imagine carrying the burden of people’s dreams and expectations; imagine being able to have everything you desire — money, sex, fame, riches — everything except that which the God you believed in denied you and which you desired most of all — peace of mind. Who would not go mad?

THE SONG

In 1971, in a club in Los Angeles, the country singer Mickey Newbury performed an impromptu medley of three traditional songs: “Dixie”, “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” and “All My Trials”. At a time when America was being torn apart by racial and cultural strife, the medley was a gesture of reconciliation that carried a potentially explosive potency.

“Dixie”, which had originated in blackface minstrel shows of the 1850s, was strongly identified with slavery and the Confederate cause: in the late 1960s, with the rise of the Civil Rights movement, its performance had been banned in some states. In direct opposition to that, “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” was the marching song of the Union Army during the American Civil War, while “All My Trials” is a spiritual of uncertain origin that became popular among folk singers during the protest movements of the late 1950s and 1960s.

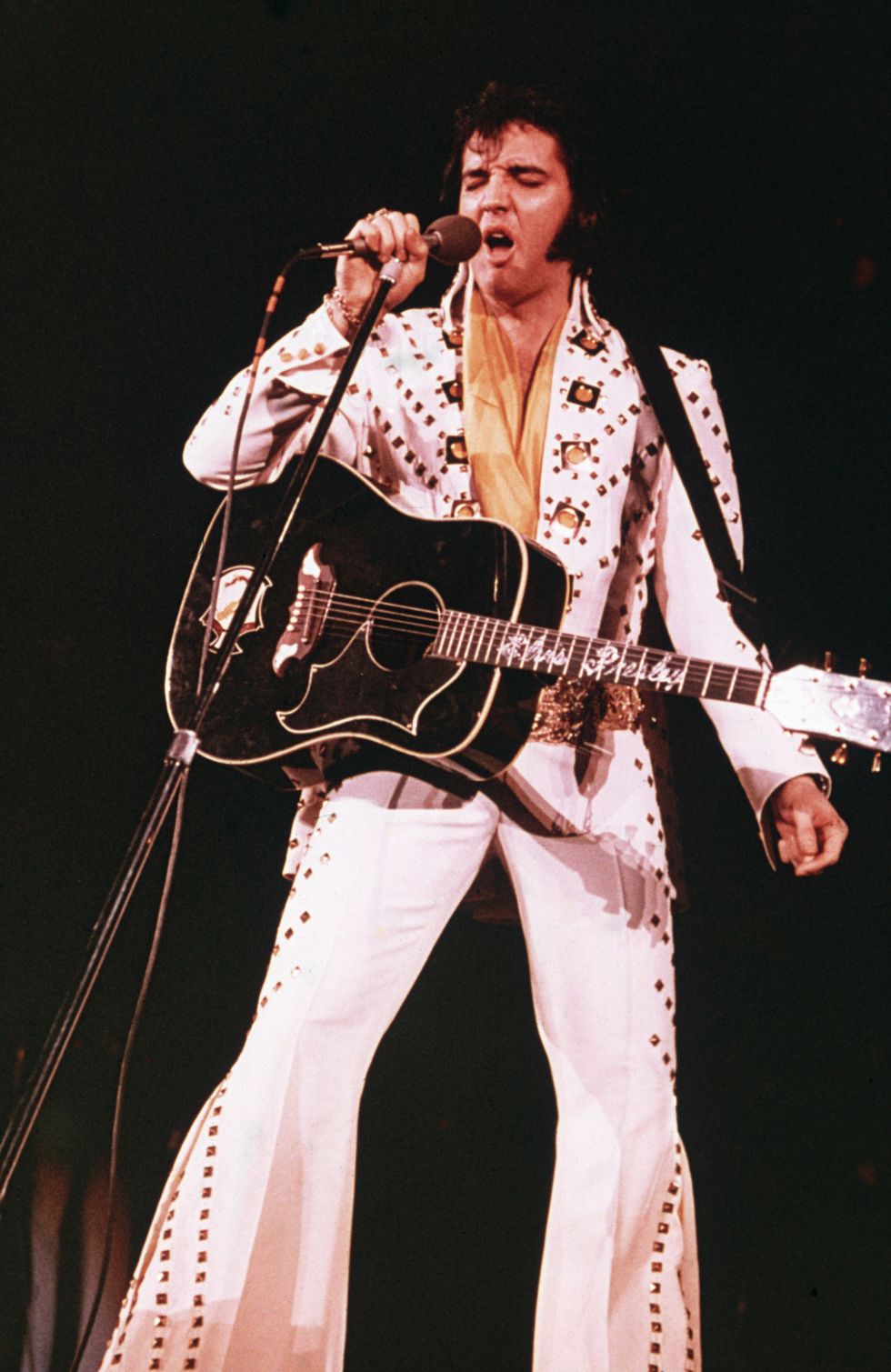

The year after Newbury had recorded the song, Elvis began including it in his live performances, and it became the centrepiece of his act thereafter. You can watch him performing it in Aloha From Hawaii via Satellite, live in Honolulu, in January 1973 on YouTube (above).

Driven on by the demands of the Colonel, 1973 was the year in which Elvis would perform 168 concerts, his busiest ever, the year in which his already parlous health would go into perilous decline. Twice he would overdose on barbiturates, spending three days in a coma in his hotel suite after the first incident, and towards the end of the year he would be hospitalised, semi-comatose from the effects of his addiction to the pain-killer pethidine.

In Hawaii, he is dressed in his white spangled jumpsuit; a huge diamond ring glitters on one finger of the hand clasping the microphone. He is accompanied by an orchestra, a white close-harmony gospel quartet and a trio of black female singers, the Sweet Inspirations. Everything about it — the arrangement, the costumes, the production — should be kitsch, overblown, an exercise in contrived sentimentality. But it transcends all that, becoming something magnificent, beautiful and touching. It is Elvis in excelsis. The most American song that this most American of artists ever sang. A song about his country that he makes a song about himself. He is an artist in complete command, the voice like flawless velvet. Sweat runs in rivulets across his forehead and down his cheeks as he sings the chorus of “All My Trials” — “Hush little baby, don’t you cry, you know your daddy’s bound to die, but all my trials, Lord, will soon be over.” The key changes. As the drums sound three beats, signalling the coming crescendo, he gives a snarl of exultation and defiance, then hymns, full-throated, the final line. “Glory, glory, Hallelujah, his truth is marching on.”

Four years from death, but unbeaten, unbowed, triumphant, the once and forever King.