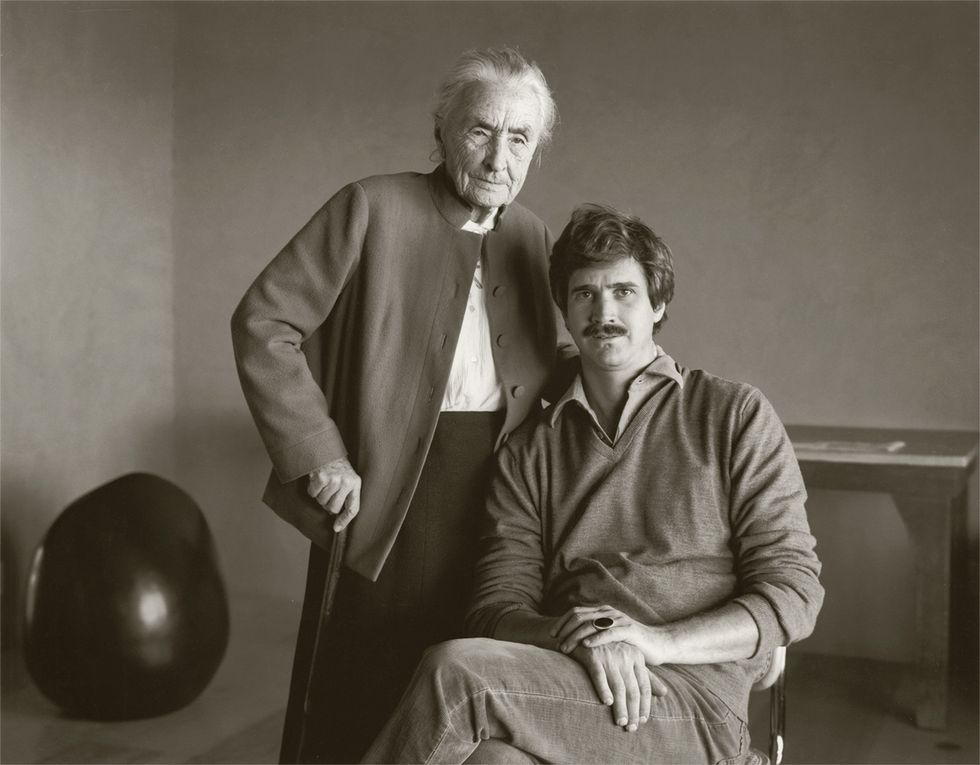

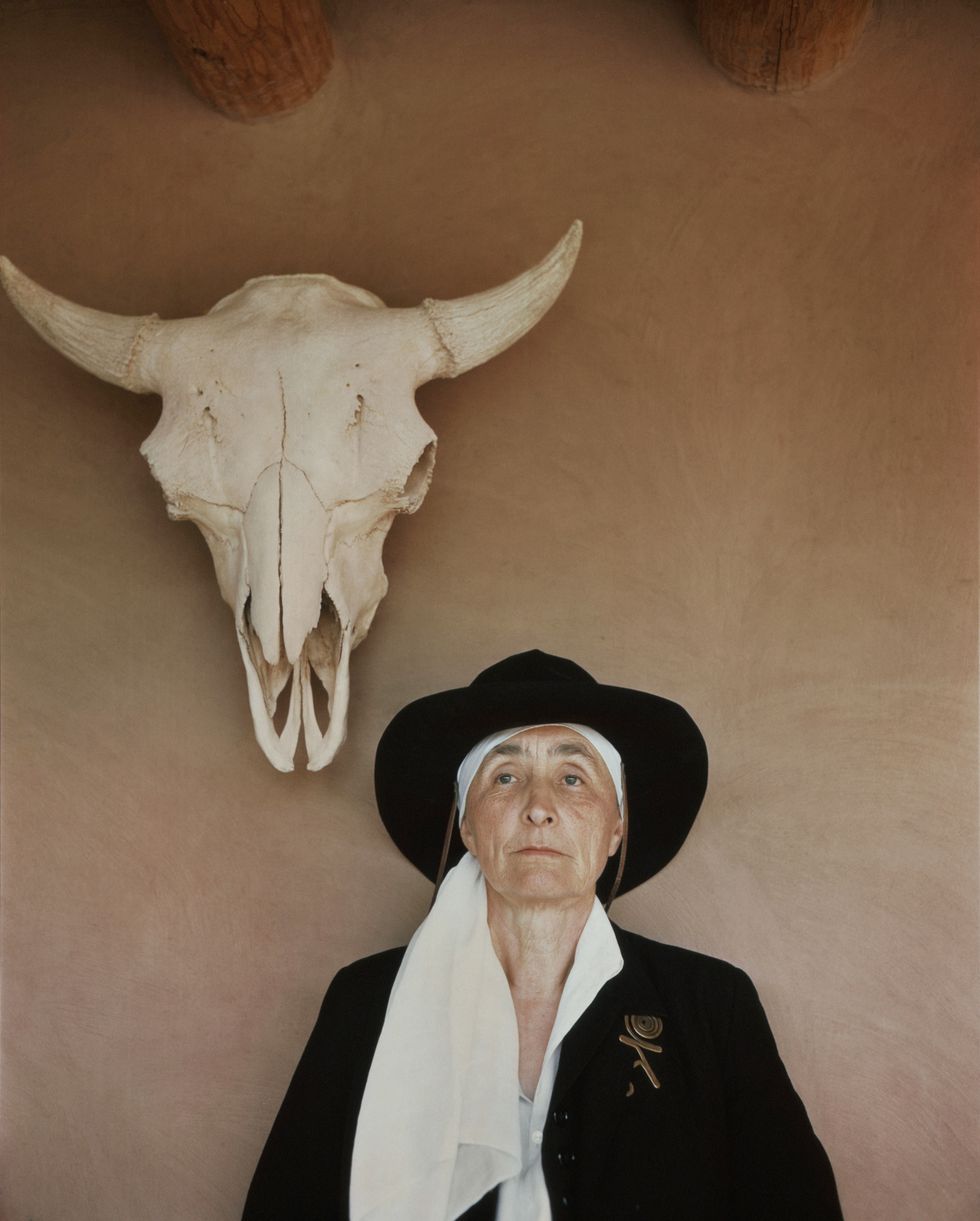

Juan Hamilton was a broke 27-year-old when he first walked into Georgia O'Keeffe's secluded studio in Ghost Ranch, New Mexico, hoping she might give him a job. It was 1973, and O'Keeffe—whose vibrant, impeccably distilled creations remain a cornerstone of American modernism—had long been renowned for her large-scale paintings of curvaceous, brilliantly colored flowers and blue-skied desert landscapes. At 85, she still had her feline beauty (famously captured by her late husband, the photographer Alfred Stieglitz, who caused a furor when he exhibited dozens of nude portraits of her in 1921—while he was still married to another woman), but her vision was suffering from macular degeneration. "It was a powerful experience, seeing her that first time," recalls Hamilton, who had moved to New Mexico from Vermont just months earlier, fleeing a painful divorce and looking for a fresh start. "Right behind her, there was this large, broken Indian pot with a skull inside, a human skull. I remember thinking, Gosh, that's just how I feel—like a bare skull and a broken pot."

O'Keeffe, however, was in no mood for unannounced visitors. Hamilton had accompanied his friend Ray McCall to fix the plumbing at O'Keeffe's adobe home, and the reclusive artist was annoyed when two men came instead of one. "After we left she called Ray and said, 'Don't you ever bring anybody else here again without asking me first,' " says Hamilton, now 70. "So I thought, Well, so much for getting to know her."

O'Keeffe ultimately did give Hamilton a job, and then some: He now lives in Abiquiú, the site of her second home, tucked among chalky-white cliffs and windswept cottonwood trees about 15 miles south of Ghost Ranch. She bequeathed both houses to him, along with the better part of her $70 million estate, when she died at age 98 in 1986—prompting lawsuits from her surviving family members, some of whom believed that Hamilton had conned his way into her will (and, according to some accusations, into her bed). "Rumors abounded that Georgia and I were secretly married, but Georgia just thought that was funny as could be—she loved it," Hamilton tells me over the phone. Soft-spoken and wary of press, he hasn't given an interview in more than a decade; he agreed to speak in light of a major upcoming O'Keeffe retrospective, which will open at Tate Modern in London this summer. "Georgia said, 'All the men artists can have young women, but people think it's shocking that I might have a young man in my life,' " he continues. "Of course, she'd gotten over the sensitivity—you wouldn't believe the things that were said about her and Stieglitz. He was 23 years older than her, and still married to his first wife when they began their affair. Imagine such behavior! Photographing her nude, and so forth. I'd get upset about what people said, but she'd just say, 'Oh, for Christ's sake, Juan, what do you care what they think? Just focus on your work.' "

Hamilton was also an artist, trained in pottery by Henry Takemoto at Claremont Graduate School in California. Raised by missionaries in South America, he was originally drawn to Ghost Ranch by an acquaintance who'd promised him carpentry work at a local Benedictine monastery. He was familiar with O'Keeffe, of course, but wasn't under any illusions that they'd become best friends. "In 1968, my mother sent me a copy of Life magazine with Georgia on the cover," he recalls. "It had pictures of her in the desert by herself with her dog, and she seemed like a monastic person who loved to be alone and work alone."

After the plumbing run-in, Hamilton returned to O'Keeffe's house a few months later at the suggestion of her former secretary, who told him that if he wanted work he had to go early in the morning and knock on the kitchen door. O'Keeffe answered and asked if he could pack a shipping crate. "I told her yes," he says. "She said, 'Did you graduate from high school?' And I said, 'Yes, and college and two years of graduate school. You'd think I could do better than pack a shipping crate.' And she said, 'You probably could if you wanted to.' "

The shipping crate was the beginning of a series of tests. After he finished, O'Keeffe presented Hamilton with a gallon jar of bent nails and asked him to straighten them. "I told her that I would if she wanted me to, but she could buy new ones for less money," he remembers. "She said, 'You didn't go through the Depression. Straighten up the nails.' So I did." O'Keeffe was pleased, and began assigning him more personal tasks. "She paid me five dollars an hour to work in the garden, six dollars an hour to drive her places, and seven dollars an hour to type," says Hamilton. "It wasn't a high-paying job, but I didn't have anything else going on in my life—I was recently divorced and starting a new life, and Georgia was one of the most interesting women I had ever met." On top of organizing her own estate, O'Keeffe had a lot of unfinished business with Stieglitz's, and Hamilton began helping with the paperwork. "The next thing I knew, I was there 10 to 12 hours a day," he says.

Their relationship grew more complicated a few months later, however, when the architect Alexander Girard and his wife, Susan—old friends of O'Keeffe's—invited her to Morocco and told her she could bring a friend if she wanted. "So she asked me to come with her," recounts Hamilton. "And that's when the trouble started."

According to Hamilton, O'Keeffe's longtime agent back in New York, Doris Bry, was already alarmed by the growing presence of the artist's strapping, mustachioed young companion, and even more so when he usurped what she considered to be her rightful spot on the Morocco trip. "Other people were upset that Georgia didn't invite them, but she was just being practical. She wanted somebody she could boss around and who could carry her suitcases, someone who could go on a walk with her," he explains. "So we went off to Morocco and traveled almost 3,000 miles together during a month and a half or two. We went everywhere together, and we got along. I could help her feel independent. She would tell people, 'He is my eyes and my ears.' " The job wasn't always a picnic, though. "She was pretty demanding," he adds. "She was no flower. And when she was in a bad mood, boy, she was tough! But over time she developed an affection for me that I wasn't expecting or looking for."

Hamilton still isn't quite sure exactly why O'Keeffe took to him over her many admirers, but he has a few theories. "I think it was because I was available, I was young, and I was tall and thin—she liked thin people," he says. "She didn't want any overweight people around her. She was high-minded about everything, not just art. She was very specific about the dimensions of things, the placement of a window, where the light comes in. The magic of how you put a flower in a vase, how you put the vase on a table." Hamilton was sensitive to her needs, and easy to be around. "I didn't put her on a pedestal or say, 'Oh, I'm so honored,' or any of that stuff," he says. "I was just a handyman who became her ally. Whenever I walked in the door, she would say, 'Oh, Juan, I'm so glad to see you.' And after having my first wife run off with another man, it was nice to be appreciated."

Hamilton was also a sponge for O'Keeffe's stories. "Her mind was sharp and bright, and she remembered every detail about the first time she went to Stieglitz's gallery—what she said, what he said, and what the elevator was like," says Hamilton. "She loved to talk about her past. I think her marriage to Stieglitz was difficult. He insisted on them getting married, and she agreed to it. But she said she cried all night before it, and just didn't feel it was right."

O'Keeffe's relationship with Hamilton grew increasingly intimate, to the mounting suspicions of O'Keeffe's friends and neighbors. "People had a hard time believing that a man and a woman almost 60 years apart could develop a friendship like we had. They'd say, 'That guy must have ulterior motives. He must be after her money,' " Hamilton says. O'Keeffe's cook was among his enemies, and she even tried to starve him out when he began spending nights at the house. "The cook said, 'Miss O'Keeffe, I will prepare meals for you, but not for your help.' But Georgia wouldn't stand for that, and the cook left and told a newspaper that when I stayed at Georgia's house, the floor of my room was a sea of beer cans in the morning," says Hamilton. "I did like to drink beer—but not a sea of it!" O'Keeffe also got anonymous phone calls from disapproving locals. "They'd say, 'That young man of yours, he was driving 90 miles an hour and he almost hit me.' And Georgia said, 'Oh, really? Why should I take you seriously if you won't even tell me your name?' The funny thing was that Georgia liked to drive fast too."

O'Keeffe was protective, but she could also be possessive. "Once, when we were in New York, a wealthy friend of Georgia's asked to borrow me to hang pictures in her penthouse," Hamilton says. "I went over and did it, and it wasn't a big deal, but Georgia was so angry when she found out. She said, 'The nerve of her. I know she had other intentions.' I'm not going to speculate about what those intentions were, but the woman had recently separated from her husband, so you can guess. But that's all trash talk, and that's what people like to do—gossip."

O'Keeffe also encouraged Hamilton to pursue his abstract, undulating clay sculptures, and in 1978 he got his first show in New York, at the Robert Miller Gallery. "Warhol and Joni Mitchell came to my opening—I couldn't believe it!" he says. "But then Georgia's [former] agent also came and served me with a lawsuit right there, for $13 million." Charging that Hamilton caused "malicious interference" in her and O'Keeffe's relationship, the suit attracted unwanted media attention. "One reporter asked me about the lawsuit, and I think they printed the quote, '$13 million, that's a lot of pots,' " he says. "I don't think it was too smart to say that."

The rumors about O'Keeffe and Hamilton persisted even after he got married—to a woman he'd met at O'Keeffe's house, no less. "I arrived one morning, and Anna Marie was waiting in the driveway with a friend, hoping to meet Georgia," he says. "In the first 15 minutes with Anna Marie, I knew I was in trouble. I told Georgia, and she said, 'Good. You'll need somebody when I'm gone.' "

After O'Keeffe died, Hamilton quickly gave over most of what she'd left him to her family's estate, which is now controlled by a board of trustees (he serves as a special consultant). "There was a lot of talk about how much money I got, but I turned down a huge amount just to have my freedom," he says. "I'm not living off what Georgia left me; I've been living off my own work and wits."

Still, he remains a huge part of making O'Keeffe's legacy what she wanted it to be. "She was very much aware of her work's quality. She graded her own paintings, and she could be very hard on herself," he says. "A lot of the things that have been written about her diminish the importance of who she really was. She's emphasized as a woman painter, and she didn't want to be one of the best woman painters. She wanted to be one of the best painters."

This article originally appeared in the March 2016 issue of Harper's BAZAAR.