Nicotiana rustica

Johannes Wilbert’s impossibly comprehensive study of tobacco has stood the test of decades: “Tobacco in traditional South American societies […] is shown to have played a culture-building role. Functioning as an actualizing principle between the telluric and the cosmic, it has served to validate the normative behavior and to affirm cultural institutions.”

Wilbert documents (with a certain amount of chagrin due to his scientific purism) the coexistence of a variety of plants in combination with tobacco: “Especially vexing, in this regard, is the overlapping geographical distributions of potential source plants and the simultaneous use of snuffs derived from them within the same region or tribe. Consequently, tobacco snuffing is not always clearly distinguishable from that of other intoxicating materials. Further exasperating the problem is the practice, in some societies, of blending tobacco with yopo (prepared from Anadenanthera), parica (from Virola), coca (from Erythroxylem), or still other substances.”

Wilbert confirms the fundamental importance of this plant among a vast range of Amerindian cultures: “In terms of geographic reach and cultural penetration, tobacco has few, if any, rivals among psychotropic plants in pre- and postindustrial societies.”

Russell and Rahman agree wholeheartedly: “…Regardless of location, the one plant used more than any other was tobacco. Virtually every Amerindian society knew tobacco.”

And so does the major researcher and co-inventor of the term entheogen, Jonathan Ott: “Tobacco, manifestly, is the fundamental and irrecusable element of American shamanic entheognosia. Virtually no well-known American shamanic inebriant exists independently of some connection with tobacco…”

In an astonishing demonstration of linguistic detective work, Roland B. Dixon documents hundreds of Amerindian words for tobacco used by indigenous groups from Alaska to Patagonia. His most important conclusion (from 1921) seems to corroborate current research described by Russell and Rahman that the ancestral plants of Nicotiana rustica are believed to be N. paniculata and N. undulata, both from North-Central Peru. From his vantage point as a linguist, Dixon affirms the importance of the Quechua word for tobacco still used by Peruvian shamans (according to Francoise Barbira Freedman): “Only one case has been found in which a single stem seems to have a wide distribution among unrelated languages, that of sairi, for which, however, no extra-American source can be claimed. The situation is, in fact, just what would be expected if tobacco had been known and used by the American Indians for centuries or even thousands of years.”

Barbira Freedman reveals amazing details as to how tobacco is essential for nourishing the yausa, or yachay, the “knowledge-phlegm” that the shaman keeps in his trachea. This phlegm contains darts that hold shamanic power as well as small animals called karawa that include scorpions, spiders and millipedes received from other shamans as gifts or stolen as they emerge from the mouths of moribund healers. Barbira Freedman says that “without tobacco smoke and also tobacco juice as regular food, these entities become inactive and impotent, not responding to shamans’ agentive intentions.”

Robert Hall mentions an extremely important idea regarding the ubiquitous nature of this plant-teacher in Amerindian rituals: “The main evidence of antiquity is the pervading holiness of tobacco. It was a sacrifice, a ritual fumigant, a good-will offering, and a sacrament. It was used to seal treaties, friendships, and solemn, binding agreements, to begin war, conclude peace, and legitimize covenants of every description between man and man, between man and the supernatural. Tobacco was used in rites of curing and in rites of human sacrifice.”

And because one can never say enough about the enormous significance of tobacco, I was fascinated by the metaphor that appears in this reflection by Glenn H. Shepard, Jr., in an article about his experiences doing fieldwork with Peru’s Matsigenka. He was told the following about the tobacco paste called opatsa seri that this indigenous group prepares for shamanic purposes: “When you swallow it, it is like planting a seed in your heart… Each time you take opatsa seri, your soul grows like a tree.”

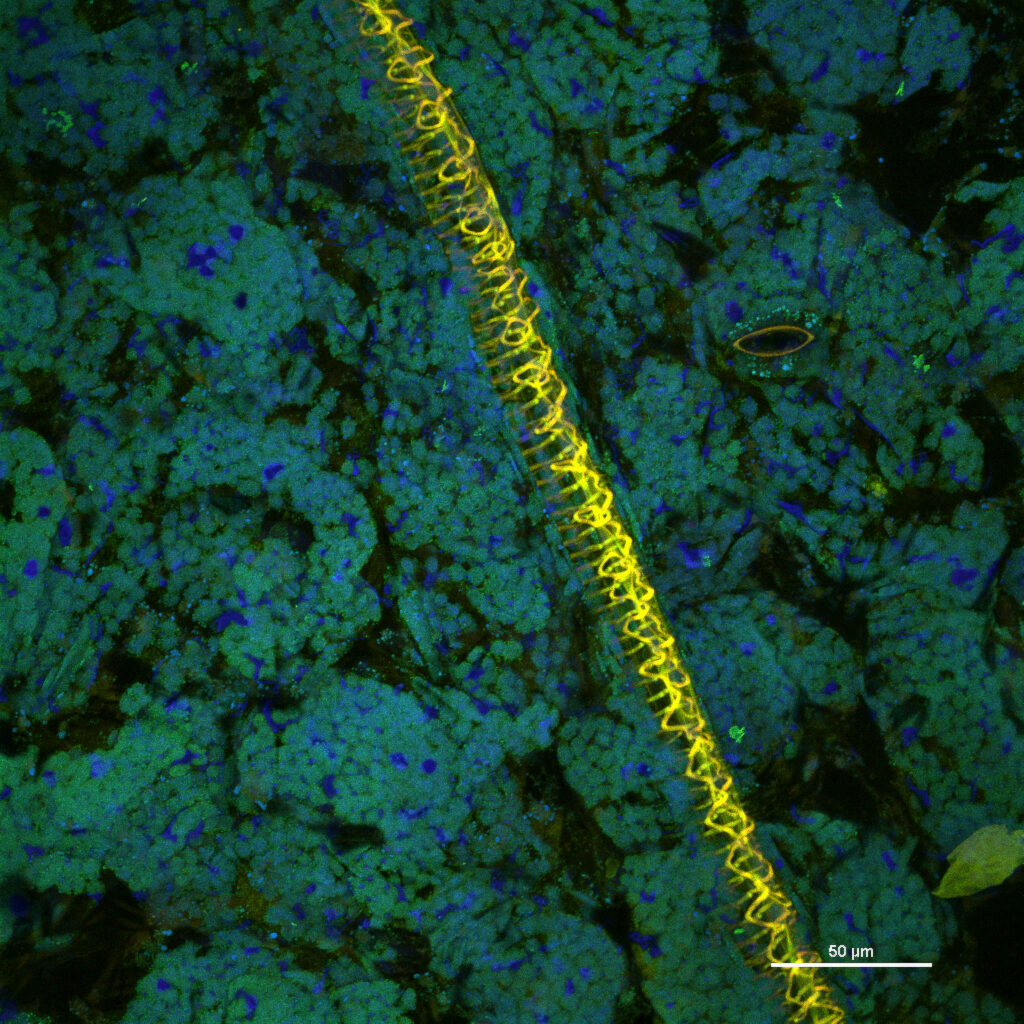

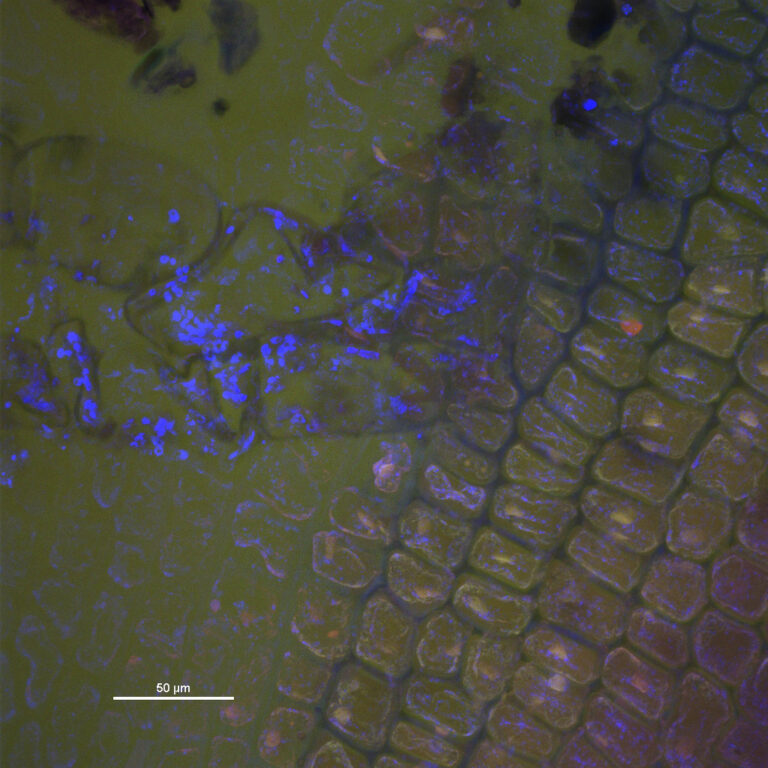

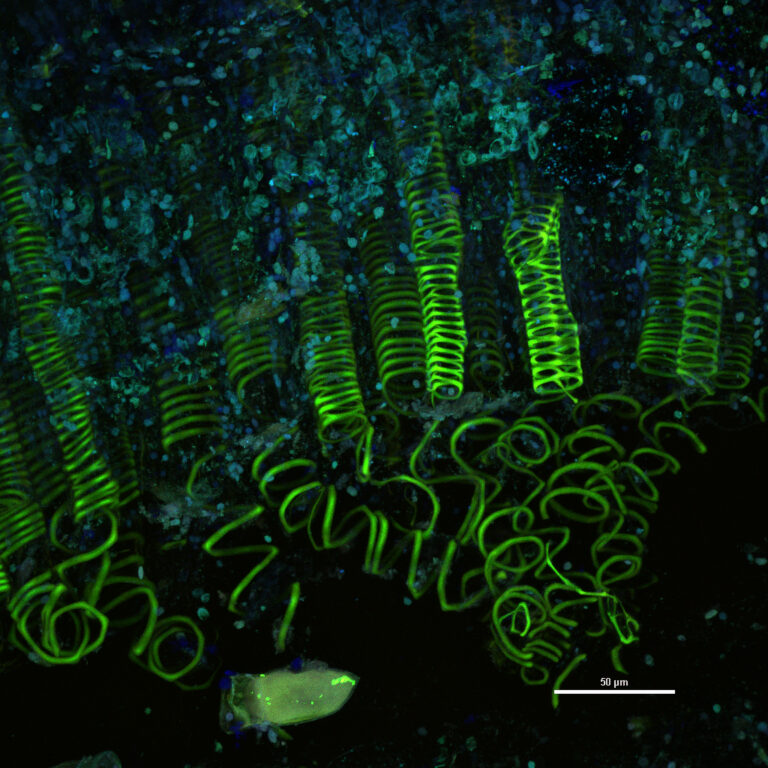

One of the confocal images we include here in the website is a visual enactment of this botanical analogy: microscopic Nicotiana rustica shapeshifting and becoming a tree. Sustainable Seed Company, the vendor of these seeds, which I was able to germinate, says the following in a catalog description: “This is only the third time this tobacco seed has been grown since it was unearthed in a 1,000-year-old archeological site on Vancouver Island. Talk about an heirloom tobacco!”

New evidence from an archaeological site in what is now northwestern Utah suggests that humans were using tobacco at least 12,300 years ago (see Nuwer).