Millions barred from 2020 hajj pilgrimage to Mecca due to pandemic

The hajj is one of the world’s greatest yearly gatherings, but coronavirus isn’t the first disruption this event has seen over the centuries.

One of the largest annual gatherings on Earth, the pilgrimage, or hajj, to Mecca, will be off-limits to most the world’s Muslims this year due to the threat of the coronavirus pandemic. After weeks of speculation—and just before the official pilgrimage is scheduled to begin in late July—Saudi Arabia announced that it will not cancel the hajj but rather severely limit attendance to the sacred gathering only to some Muslims currently residing in the country.

In normal years, more than 2 million of the world’s 1.8 billion Muslims travel to Mecca to perform the hajj, which is considered the fifth and final Pillar of Islam. Every Muslim adult who is financially and physically capable must complete at least one hajj, and for many, it’s the trip of a lifetime. This year, however, experts estimate that only 1,000 of Saudi Arabia’s 29 million Muslim residents will be allowed to attend.

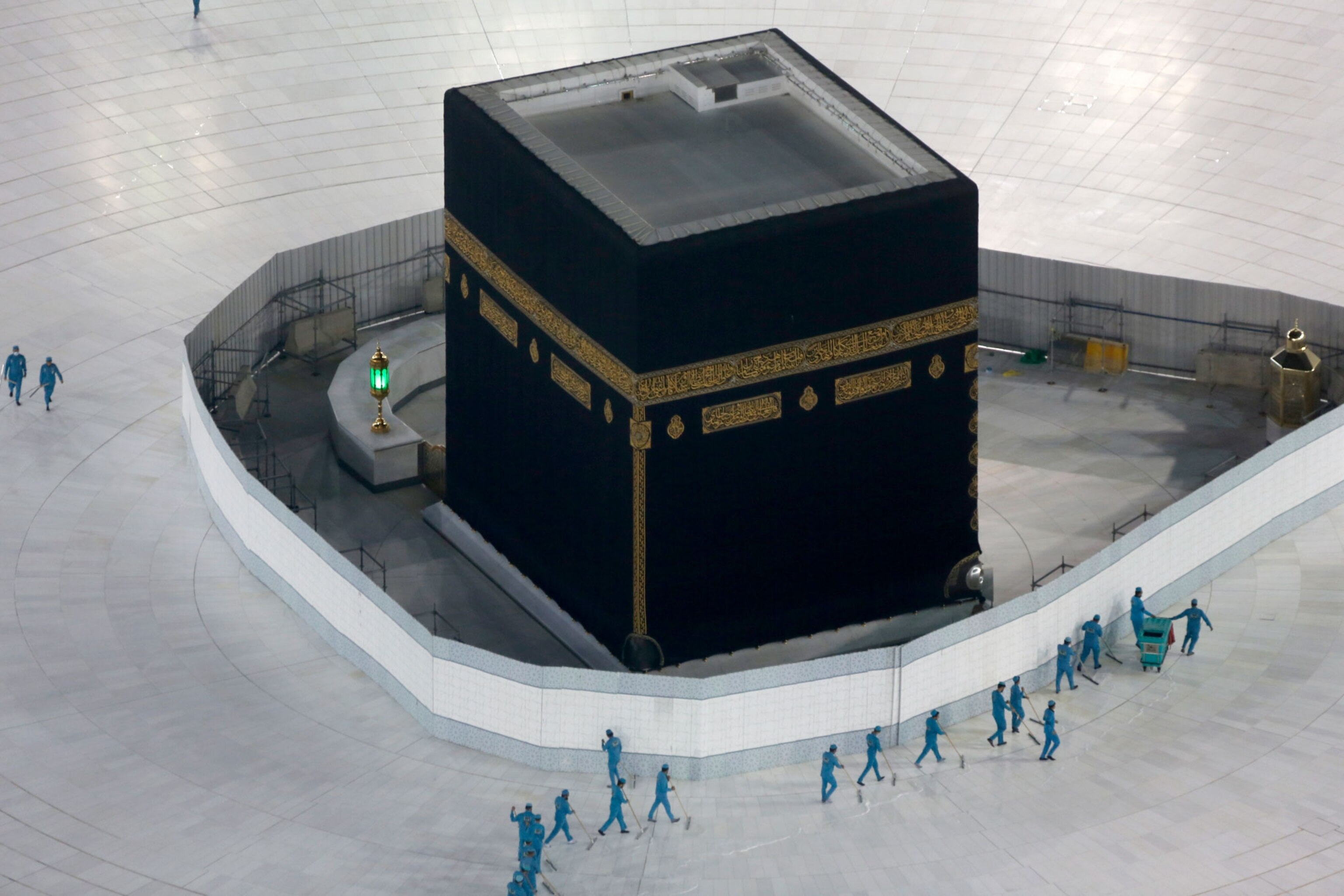

During hajj, millions converge first on the tent city of Mina, then travel to Mount Arafat, the Grand Mosque of Mecca, and other locations. At each stop of the five- or six-day journey, they meet other Muslims, pray together, and perform deeply symbolic rituals. Pilgrims wear special white garments and enter the sacred state of Ihram, which prohibits things like cutting hair or nails or engaging in sexual relations.

Although several nations have already prohibited their citizens from attending hajj, the news is still a painful blow precisely because part of the power of the pilgrimage is the way it brings together the global Muslim community, according to Omid Safi, a professor of Islamic Studies at Duke University. “The hajj is more than just a religious ritual,” Safi says. “At its best, it is a symbol of the radical egalitarianism of Islamic ideals. Ideas and goods get exchanged, and so do mystical ideas.”

War, famine, and disease

While this is the first time Saudi Arabia, considered the custodian of Mecca since the country’s establishment in 1932, has shut the door to all Muslims outside the country, it’s certainly not the first the hajj has been interrupted: Since the first official hajj was led by the Prophet Mohammed in A.D. 632, the pilgrimage has been subjected to “wars, famines, diseases, and political interruptions,” Safi says.

According to historians at the King Abdulaziz Foundation for Research and Archives, the hajj has been interrupted at least 40 times since 930, when members of a Shiite sect called the Qarmatians sacked Mecca, and murdered 30,000 pilgrims. Qarmatians also stole and held for ransom one of Islam’s most precious relics, the Black Stone of the Kaaba, and the hajj was suspended for a decade until the stone was returned to Mecca.

Epidemics have also interrupted past pilgrimages. Cholera has cost tens of thousands of pilgrims’ lives in the 19th century; in 1821, for example, 20,000 died, and in 1865 pilgrims from the Ganges Delta brought the disease to Mecca where it spread to pilgrims from other countries and eventually contributed to a worldwide death toll of 200,000. In more recent memory, political disruptions and diplomatic issues have prevented some pilgrims from converging on Mecca.

A devastating financial cost

In addition to the religious implications of limiting the hajj, the economic impact also will be significant. Though the hajj is attended by pilgrims from a range of economic backgrounds, food, visa, and lodging costs for the multi-day ritual can run into the thousands or tens of thousands of dollars per person, and many save their entire lives to attend. “Restaurants, travel agents, airlines and mobile phone companies all earn big bucks during the hajj,” notes the BBC Arabic’s Ahmed Maher, “and the government benefits in the form of taxes.”

According to Reuters, the hajj and other pilgrimages to Mecca during the year, known as Umrah, normally generate about $12 billion per year, or roughly 20 percent of the country’s non-petroleum GDP.

“[This hajj decision] is an extraordinary piece of news,” says Simon Henderson, a Saudi Arabia expert at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. “This will knock local economies.”

Though Saudi Arabia lifted a nationwide curfew on June 21, it is still dealing with coronavirus; to date more than 150,000 people in Saudi Arabia have been infected and 1,400 people have died.

Though the severe restriction on hajj attendance will likely save many lives, it will also further disrupt daily life in a nation that finds pride and profit in hosting one of the world’s largest religious gatherings. One casualty will be the nearby city of Jeddah, where most pilgrims arrive to begin their pilgrimage in Saudi Arabia. “Traditionally and historically, Jeddah’s prosperity has been based on looking after hajj Pilgrims,” Henderson says. “This time they’re not going to be able to do that.” Neither will Saudi Arabia’s ruler, King Salman, who is considered the custodian of the holy cities of Mecca and Medina—or the Saudi people themselves.

“It’s the sensible thing to do, but it’s a knock to Saudi self-esteem,” says Henderson. “To stop it is a shock to the system.”

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- How scientists are piecing together a sperm whale ‘alphabet’How scientists are piecing together a sperm whale ‘alphabet’

- Orangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first timeOrangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first time

- What La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planetsWhat La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planets

- This fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then dieThis fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then die

Environment

- This floating flower is beautiful—but it's wreaking havoc on NigeriaThis floating flower is beautiful—but it's wreaking havoc on Nigeria

- What the Aral Sea might teach us about life after disasterWhat the Aral Sea might teach us about life after disaster

- What La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planetsWhat La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planets

- How fungi form ‘fairy rings’ and inspire superstitionsHow fungi form ‘fairy rings’ and inspire superstitions

- Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

History & Culture

- These were the real rules of courtship in the ‘Bridgerton’ eraThese were the real rules of courtship in the ‘Bridgerton’ era

- A short history of the Met Gala and its iconic looksA short history of the Met Gala and its iconic looks

- Meet the ruthless king who unified the Kingdom of Hawai'iMeet the ruthless king who unified the Kingdom of Hawai'i

- Hawaii's Lei Day is about so much more than flowersHawaii's Lei Day is about so much more than flowers

Science

- Why ovaries are so crucial to women’s health and longevityWhy ovaries are so crucial to women’s health and longevity

- Orangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first timeOrangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first time

Travel

- Why this unlikely UK destination should be on your radarWhy this unlikely UK destination should be on your radar