- Measuring the Sun is tricky business, as direct observations rely on solar eclipses to get an accurate measurement of the Sun’s light-emitting photosphere.

- However, measurements in the 1990s using f-mode frequencies, or f-waves, found the Sun to actually be a few hundredths of a percent smaller than implied by these typical photospheric measurements.

- Now a new study by a group of helioseismologists (yes, that’s a thing) have confirmed this f-wave size using sound waves called p-waves.

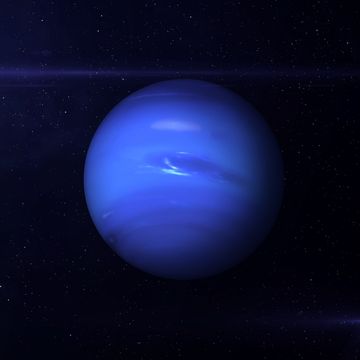

When it comes to things that are big, nothing comes close to the immense size of the Sun (at least, not in our Solar System). But even though Earth has basked in its radiance for 4.6 billion years, scientists aren’t sure exactly how big the Sun is. Measuring the Sun, it turns out, isn’t as easy as it might seem.

Previous studies have measured the Sun by its photosphere, which is the part of the star from which light is emitted. This stellar measuring is often done during solar eclipses, which are particularly useful for their ability to block the Sun’s blinding rays while revealing the star’s otherwise invisible corona. Those methods have given us an approximate diameter of 864,000 miles (1,390,000 km) and an approximate circumference of 2,714,000 miles (4,368,000 km).

However, in the field of helioseismology—which studies the interior of the Sun through its surface vibrations—researchers have also made use of sound waves known as f-mode frequencies, or f-waves, to get a more accurate picture of the Sun’s size. By this method, the Sun actually seems to clock in at a few hundredths of percent smaller than it does when measured by photospheric means.

Now, two astrophysicists from the University of Cambridge and the University of Tokyo have confirmed this smaller figure by measuring the solar radius using p-waves, which are created by material moving inside the Sun and can easily pass through the core. The results of the study were published on the preprint server arXiv in mid-October.

“Analysis of f-mode frequencies has provided a measure of the radius of the Sun which is lower, by a few hundredths percent, than the photospheric radius determined by direct optical measurement,” the paper reads. “We find that that radius is more-or-less consistent with what is suggested by the f modes.”

The calculation returned a size differential that was a few hundredths of a percent smaller than the one from photosphere measurements. But while “a few hundredths of a percent” may not seem like much, when you’re talking about something the size of the Sun, that tiny difference can have big implications.

The University of Cambridge’s Douglas Gough, who originally coined the term “helioseismology,” said in an interview with New Scientist that this discrepancy in size can speak to differences in “nuclear reactions, the chemical composition and the basic structure of the Sun.”

The wrong radius can also lead scientists to different conclusions about how certain layers of the Sun operate, so it’s vital to have an accurate size figure when exploring the endless complexity of our host star. It only took millennia of stargazing, but astronomers may have finally sized of up the Sun for good.

Darren lives in Portland, has a cat, and writes/edits about sci-fi and how our world works. You can find his previous stuff at Gizmodo and Paste if you look hard enough.