- Guédelon is a “modest castle” in France, which authentic historical craftspeople are building.

- Stone is rarely used to bear weight in buildings today, but it was the best option in the 13th century.

- This decades-long project helps train new workers, entertain visitors, and advance archaeological studies.

It’s been 26 years since a small group of people began building Guédelon Castle in central France, using only historically accurate medieval tools and methods. Hundreds of thousands of people visit each year to see a staff of about 70 craftspeople and artisans work on the building, its interiors, and even the grounds’ period-correct garden. With technology captured in time from the 13th century, the question at Guédelon isn’t so much what has changed—but instead, what hasn’t?

Breaking Ground

Guédelon Castle began with a series of happy accidents, and it sounds almost like a supersized episode of the British dream home show Grand Designs. (Coincidentally, that show began in 1999, just two years after builders broke ground in Guédelon.) Michel Guyot is described by the press as a French entrepreneur, but he is now famous for his castle investments. He first invested at just age 29 or 30, with his literal “frere Jacques,” when they bought an empty French chateau to fix up in 1979. In 1995, a team of archaeologists told Guyot that the outer walls of the chateau were built around a medieval castle whose original walls were intact.

What happened next started it all, according to the Guédelon Castle website. At the end of their reported findings, the archaeologists wrote: “Reconstructing Saint-Fargeau castle would be an amazing project.” Guyot and two collaborators, including Maryline Martin, who has stayed in a hands-on leadership job with the project since its inception, decided they should plan and build a brand-new castle as a way to avoid being hemmed in by existing ruins.

Guyot and company decided to build the new castle in the style used in the 13th century, including a historically accurate design from an expert architect. That means trained artisans and craftspeople would be required to carry out different types of masonry, blacksmithing, carpentry, dyeing, animal husbandry—everything needed to recreate the kind of building site you might see in the 1200s, when workers would not commute to and from the site each day with an hourlong train or bus ride. The building site became its own village.

Show-stopping ancient construction like Chartres Cathedral or the Great Pyramid at Giza took 20 years or longer. Today, construction of science facilities can take decades of fabrication and building, as can ambitious public works projects like Boston’s infamous Big Dig. Guédelon’s communications director told NPR the decider in medieval days was simply money; castles were monuments to power and affluence as well as military fortresses, not emblems of international energy cooperation or a way to streamline daily 21st-century traffic for the commoners.

In a piece on NPR in October, workers at Guédelon estimated that the rest of their work, already 26 years in, could take up to 20 more years. That’s partly because the goal is not expediency. The site is considered a working archaeology project. By doing this labor the traditional way, workers are helping those who study medieval castles (“castellologists”) to understand more about how they were really built in history. And, as would have happened in medieval times, the long building process has become the longest portion of some workers’ careers.

Here’s a glimpse at some of the building materials and technologies in use at Guédelon—and how they stack up against modern construction methods.

Stone

Today, few buildings are built from load-bearing stone. They might have a stone facade as an aesthetic choice, but the insides are usually concrete or even reinforced concrete, something that was not part of the 13th-century repertoire. Romans had invented and refined cement for some kinds of projects, but stone and brick were still the go-to materials for larger structures. And builders have used versions of mortar since ancient times, combining lime or gypsum with additives like natural glue, dairy proteins, animal fat, egg whites, oils, blood, and beer, researchers explained in a 2015 paper published in the peer-reviewed journal Archaeometry.

Mortar fills gaps, helps rocks cling to each other, and also imbues buildings with the elasticity they need to endure continuous loads. Wood naturally has a great amount of flexion, which means walking across your floors won’t snap the boards in half; good mortar helps otherwise inflexible stone behave in much the same way. At a time when stones were hand-cut and shaped, this was key in building a structure sealed against the outside wind and weather, able to stand the test of time. For other uses, like shorter standalone walls that acted as fences or boundaries, simple stacked rocks worked just fine.

The masons at Guédelon have a working crane based on contemporary designs. NPR describes it as “like a giant hamster wheel,” and it can lift 1,000 pounds at a time. If you were using gray granite, according to one calculator, that would be a single cube of stone that’s about 22 inches long on each side. An extraordinary human being can deadlift just over 1,000 pounds, but that’s one lift and then a drop—not a trip on foot from the quarry to the waiting horse cart. In 2006, one stonecutter said each block of stone can take up to eight days to chisel in the quarry before it’s brought to the appropriate part of the building site.

And while large stone blocks have gone out of style for buildings today, they’re not unheard of. Today’s masons can procure standardized machine-cut stone blocks that cranes can rapidly place, just like human beings can rapidly place bricks. One major advantage of solid stone construction like this is that stones remain modular and recyclable. If a stone is broken, you can see right away and avoid it. Otherwise, stone blocks can be reused for all kinds of projects. Even very, very old stone could be reused this way if it were not of archaeological interest.

Wood

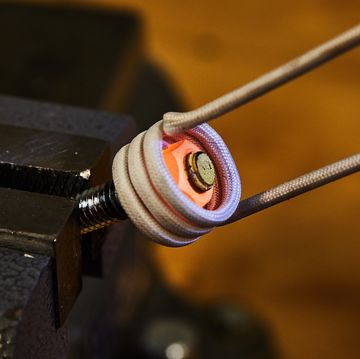

Inside a medieval stone structure like Guédelon, there’s often an extensive and detailed scaffolding of wood to support the placement of masonry. Workers were five years into construction at Guédelon before they started putting up centring, which is a wooden scaffold that holds the arched shape of a vault ceiling while workers place stones from the bottom up to the keystone. The wood is cut on site (Guédelon is situated in a dense forest) and transported with the same horse carts and medieval crane. A blacksmith on site makes all the nails used in wood construction, along with all the other tools.

Wood was also used to frame houses at the time, and at Guédelon, these are filled in using wattle and daub. This method dates back to the neolithic period, and it involves weaving slats into rough panels that are “daubed” (plastered) with whatever mixture was available. This could be mud, clay, or plaster, and was bulked with fillers like straw. Proponents of this technique today say these structures can easily last 500 years or more.

It’s true that wood does not last the simple test of time as well as stone, but the goal at Guédelon is not to make perfect ruins for the far future—it’s to build a working castle with the same values that contemporary builders would have used. And that means wood is still the most suitable material for many parts of the castle, including economically. That includes for roofs, which, as the 2019 Notre-Dame Cathedral fire showed us, were often made of wood covered in a layer of waterproof material. Wood can save a great deal of weight, but there are always pros and cons.

Paint and Dye

At Guédelon, artisans use minerals to create paints, and these are found readily in the soil and quarry. In medieval times, interior paints were often made using egg yolk, creating tempera paint, or casein, creating more of a whitewash paint or primer. Artists used oil paints sometimes, but these were expensive and not well-suited to painting interiors. With egg tempera paint, natural pigments like ocher are ground into powder and then mixed with egg yolk and a thinning extender like vinegar. It’s basically colorful mayonnaise for your walls.

For woodwork, finishing oils and varnishes date back thousands of years. Like today, wood could be finished by applying an oil and rubbing it into the wood, which would also preserve it and make it less porous. And to make varnish, artisans combined natural resin sources, like pine tar, with a solvent and oil in order to create a smooth, hard-drying finish. A resin is a usually naturally occurring substance that can be dried or treated into a strong, water-resistant polymer.

The pigments found around Guédelon, painter Claire Piot told NPR, include “ochers, some clays, some soils, charcoal, lime—things like that, and we can make 15 colors.” Ocher is a combination of earth clay and iron oxide (a different one than rust!), producing shades in the earth tones or “fall colors” family. (It’s found around the world; Georgia’s red clay soil is so iconic that cultural events in Atlanta are named after it.) Other pigments were available at the time, but medieval European castles often relied on red and yellow ocher to make their palettes, as people have done since the very earliest surviving art from hundreds of thousands of years ago.

The Takeaway

The Guédelon site is unusual for employing so many workers who are trained or apprenticing in the traditional medieval methods, but there are people all over Europe who work in preservation and education around historical sites. Historic Environment Scotland is hiring an apprentice stonemason as we speak, someone who will work on half a dozen abbeys and castles in the area that borders England.

These, like Guédelon, are long-term positions that can form entire careers. People who train at Guédelon have options, and their work recreating medieval construction has led to better understanding of building techniques. The communication lead for the project told NPR that many involved in rebuilding Notre-Dame Cathedral called to consult with Guédelon’s talented medieval workers.

In 2006, Associated Press reporter Angela Doland wrote: “Some of the walls are already covered with moss, a reminder that the project is slow-going. If all goes well, the castle will be finished in 2023. After that, the craftsmen plan to build an abbey, then a village.” That was 17 years ago, of course. In October, the builders told NPR’s Eleanor Beardsley that it could be “10, 15, even 20 more years” before Guédelon Castle is finished.

💡 Did You Know?

William Randolph Hearst built an iconic castle of his own in southern California. Today, it’s a state park and open to the public, but 100 years ago, Hearst was hosting a murderer’s row of Hollywood guests. His castle was also made using a unique mix of purchased and imported features from existing castles.

Hearst was far from the only wealthy person to build an opulent, very personalized estate like this. One notable counterproject, so to speak, was Stronghold Castle in rural northern Illinois. Walter Strong was the socially conscious owner of a much smaller media empire, the Chicago Daily News, and after visiting Hearst Castle, he decided to make his family’s summer home a much more practical one, director Jan Hartman said in 2011.

But the working site is about much more than a ribbon-cutting. Fifty-thousand visitors came during Guédelon’s first public season, and 300,000 annual visitors come each year now—enough for the castle project to sustain itself. Visitors are inspired, and some who work there today say they first visited as children.

Still, there are a couple of vital changes being made compared to the real-life past. First, the workers wear steel-toed boots. And second, their rolling medieval crane has a modern brake. In fact, the site is outfitted with thinly veiled safety equipment all around. Medieval builders did their best with protective gear, but they would marvel at today’s technology.

Caroline Delbert is a writer, avid reader, and contributing editor at Pop Mech. She's also an enthusiast of just about everything. Her favorite topics include nuclear energy, cosmology, math of everyday things, and the philosophy of it all.