SSRIs

A Better Understanding of SSRI Antidepressants

Everything you should know, and why they take so long to work.

Posted May 18, 2020 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) were introduced in 1987 with the release of Prozac, and since then have become the most common type of antidepressant used by Americans. According to Olfson and Marcus (2009), nearly 67 percent of those taking antidepressants in the United States are treated with SSRIs.

Over the past three decades, SSRIs have become the first-line treatment for depression, even though the evidence supporting the serotonin theory of depression is inconclusive, as is the evidence supporting the efficacy of SSRIs (Moncrief et al., 2022). This is largely because SSRIs tend to have fewer side effects and are less dangerous in cases of accidental overdose than their antidepressant predecessors: monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) (Santarsieri & Schwartz, 2017). Despite the better safety profile of SSRIs, many patients whom I would describe as having biological depression are resistant to trying them because they are unclear on why it could take up to a month to start working and also why they might feel worse before they feel better.

In an effort to help those considering SSRIs better understand how these drugs work, I have asked a clinical pharmacist, Dr. Margaret Tsopanarias, to explain the pharmacological and neurophysiological mechanisms of SSRIs. Dr. Tsopanarias has over 15 years of pharmacy experience, including work in clinical, research, and retail venues, and currently works at Paramount Specialty Pharmacy in New York.

---------------

JGC: John G. Cottone, Ph.D.

MT: Margaret Tsopanarias, PharmD, AAHIVP

---------------

JGC: Margaret, thank you so much for your time. I think your expertise can help inform psychologists, like me, and the patients we treat about how SSRIs actually work; why they usually take so long to start working; and why people sometimes feel worse before they feel better when they start taking them.

MT: It is my pleasure to answer any questions you have about SSRIs. Before I get into the nitty-gritty, I wanted to mention something that I feel is important. When I counsel patients on their antidepressant medication, I routinely ask, "Is this working for you?" and in response, I often hear: "I guess it is, but then again, I don't really feel any different."

All things considered, that's not a bad answer for me to hear because some people expect these medications to trigger an exaggerated euphoric response, but that's simply not the case. We need to train ourselves to understand that these medications, at best, are going to make people feel well enough to begin implementing the structural life changes recommended by their therapists. Therefore if you're taking one of these medications and you're not singing in the rain or sliding down rainbows, it doesn't mean that the medication is not working. We have to keep our expectations realistic.

JGC: Let's start with some basics: What are SSRIs, and how do they work to increase serotonin in the brain?

MT: Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors, or SSRIs, are medications that amplify the neurotransmitter serotonin (5-HT) in the brain with the hope of alleviating symptoms of depression and anxiety. They are traditionally a first-line choice for doctors to prescribe for these symptoms, based on their safety and efficacy profile. Serotonin is believed to be responsible for well-being and mood, among other things.

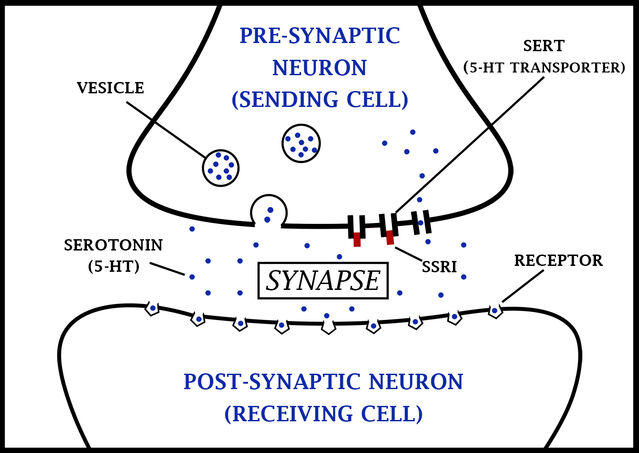

In our brains, there are sending cells and receiving cells, and the space between them is called a synapse. In depression, there is a deficiency of serotonin being sent to the receiving cell. Sometimes, the sending cell reabsorbs the serotonin before it even makes it to the receiving cell: it's as if the sending cell had a change of heart.

SSRIs work by blocking those areas where serotonin can be reabsorbed in the sending cell, therefore increasing the amount of serotonin in the gap (synapse), which can keep moving along to the receptor of the receiving cell. The exact mechanism involved isn't fully understood, but it is believed that SSRIs bind with serotonin transporters (aka SERTs), and this action blocks the reuptake of serotonin back into the "sending" cell that it came from (Lutz, 2013).

JGC: When patients that I see with severe depression or anxiety finally decide to try medication and are prescribed an SSRI, like Lexapro or Zoloft, they are often discouraged upon learning from their psychiatrist that it will take upwards of a month to start working. Can you explain why that is, and why some patients actually feel worse—more depressed or more anxious—before they start to feel better?

MT: What we often see with depression is that the receiving cell is so hungry for serotonin, it increases the number of receptors reaching out for it: this is called upregulation (Parsey et al., 2010; Kaufman et al., 2015; Stockmeier et al, 1998). When this happens, not only is there an increase in the overall number of serotonin receptors, but also an increase in the variety of serotonin receptors present. Though some of the receptor types added are related to mood, others are related to sleep, appetite, and sexual function, among other things. This is why we don't want to start with a high dose of an SSRI too quickly: If we give too high a dose, too fast, there will be a flooding of serotonin to all receptors types, including those involved in functions unrelated to mood, and this can lead to a dramatic increase in side effects.

When patients with depression are started on SSRIs, psychiatrists go low and slow to avoid side effects as much as possible, but they still occur to some extent. That's because there's still an increase of serotonin meeting the overabundance of serotonin receptors present from the upregulation phase, caused by depression. Then, over the course of a few weeks, we start to see a reduction of serotonin receptors (of all types) in response to the abundance of serotonin in the synapse: this is called downregulation (Gray et al., 2013). At this point, both the positive effects and the side effects of the drug begin to diminish.

Downregulation occurs over the first two to four weeks after starting an SSRI, which is why there is often a delay in the efficacy of SSRIs for two to four weeks (Gray et al., 2013) After the downregulation process stabilizes, psychiatrists then usually increase the dose of the SSRI slowly, and then we see a more consistent, positive effect of the drug on mood and more limited side effects if any.

JGC: As far as you know, do individuals develop tolerance to SSRIs as with some other psychiatric medications?

MT: My experience with medication therapy management, and my communication with hundreds of patients through the years, leads me to believe that tolerance of SSRIs can occur but not to the same degree as other medications or at the same schedule. When this happens, psychiatrists will start to use combination therapy, whereby combinations of medications in different classes are used.

JGC: I have also heard some patients talking about something called "SSRI poop-out," whereby their medication just stops working. Is that a real phenomenon, as far as you know, or is it more likely that these individuals had other physiological or psychological changes that intensified their symptoms?

MT: I have come across "SSRI poop-out," but not often. There is a lot of trial and error that goes into the pharmacological treatment of depression. When one fails, fortunately, we have options for alternatives and add-ons.

JGC: Finally, the ultimate goal for most of my patients taking SSRIs is to eventually come off of them. However, I know it can be dangerous for individuals taking SSRIs to just stop taking them cold turkey, without tapering off. Can you explain why this is?

MT: Neurons get used to a certain level of serotonin. When individuals taking SSRIs discontinue too quickly, this can lead to negative side effects, such as depression, anxiety, and flu-like symptoms.

JGC: Are there any other recommendations in this area that you think could be helpful, either to psychiatrists, psychologists, or the patients that we treat?

MT: It's very important to stay adherent to your medications to see positive results. If you miss a dose of your medication, take it as soon as you remember. If it's close to the next dose, skip the missed dose and resume as normal.

Do not double up on your medication. Keep all doctors informed of all the medications you are taking. It's important to make sure you are not taking other medications that may increase serotonin without your psychiatrist's awareness.

Sometimes medications that are not prescribed by psychiatrists (like Tramadol, which is used for pain, as well as certain medications used to treat migraines) can cause serotonin syndrome if taken in combination with an antidepressant. Serotonin syndrome, which is a cluster of symptoms that sometimes occurs after starting an SSRI, is not common, but if you experience symptoms such as agitation, dilated pupils, muscle weakness or rigidity, loss of coordination, or rapid heart rate, seek medical attention.

References

Olfson M, Marcus SC. National Patterns in Antidepressant Medication Treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(8):848-856.

Santarsieri D, & Schwartz T. (2015). Antidepressant efficacy and side-effect burden: A quick guide for clinicians. Drug Context. 2015;4:212290

Lutz, P. (2013). Multiple serotonergic paths to antidepressant efficacy. Journal of Neurophysiology, 109(9):2245-2249.

Parsey RV, Ogden RT, Miller JM, et al.: Higher serotonin 1A binding in a second major depression cohort: modeling and reference region considerations. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68(2):170–8. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.03.023

Stockmeier CA, Shapiro LA, Dilley GE, et al.: Increase in serotonin-1A autoreceptors in the midbrain of suicide victims with major depression-postmortem evidence for decreased serotonin activity. J Neurosci. 1998;18(18):7394–401.

Gray, N.A., Milak, M.S., [...], & Parsey, R.V. (2013). Antidepressant Treatment Reduces Serotonin-1A Autoreceptor Binding in Major Depressive Disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 74 (1): 26-31.

Kaufman J, Sullivan GM, Yang J, et al.: Quantification of the Serotonin 1A Receptor Using PET: Identification of a Potential Biomarker of Major Depression in Males. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40(7):1692–9.

Moncrieff, J., Cooper, R.E., Stockmann, T., Amendola, S., Hengartner, M.P., & Horowitz, M.A. (2022). The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic umbrella review of the evidence. Molecular Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-022-01661-0