Last year’s White House budget was a self-styled compromise offer, which put on the table concessions – like a stingier cost-of-living adjustment for Social Security, called chained Consumer Price Index, or “C-CPI” – that President Obama would accept only if Republicans reciprocated by closing tax loopholes, or making other concessions. To the surprise of nobody, they did not reciprocate, so this year’s White House budget pulls the proposal off the table.

Deficit scolds are crying hot tears of anger (Maya MacGuineas of Fix The Debt: “the nation needs the President to lead on this issue. The clear pullback on his part is a disturbing sign that he will not.”) Meanwhile, liberal Democrats are exulting (Stephanie Taylor of the progressive Change Committee: “This is a huge progressive victory.”)

In reality, the fundamentals of the situation have not changed at all. Last year, Obama was willing to adopt C-CPI in return for concessions Republicans would never, ever make. This year, Obama is still willing to adopt C-CPI in return for concessions Republicans would never, ever make. Putting the compromise in his budget was merely Obama’s way of locating the blame for the reality that Republicans in Congress will never, ever, ever strike a fiscal deal with him. The disappointed deficit scolds sitting just to Obama’s right, and the joyous progressives just to his left, are committing the same fallacy. They are mistaking a step premised on an impossibility for a semblance of reality.

I’ve seen Obama administration officials justify their contingent position on both practical and moral grounds. The practical case is that Democrats object fiercely to cutting Social Security, and they can’t cobble together the necessary votes from their party for any deal unless they get something in return. The moral case is that C-CPI places the burden of long-term debt reduction almost entirely on the middle and working classes, so fairness dictates it be balanced by some sort of progressive change. Obama has proposed closing tax deductions or loopholes that benefit the rich; I could see some other concession, like funding for pre-kindergarten education, serving this fairness function instead.

All these debates between left and center have an angels-dancing-on-the-head-of-a-pin quality to them. The Congressional Republican refusal to negotiate a long-term budget pact with Obama is the hard, core fact around which all these hypothetical arrangements revolve. Republicans claim to believe the following things:

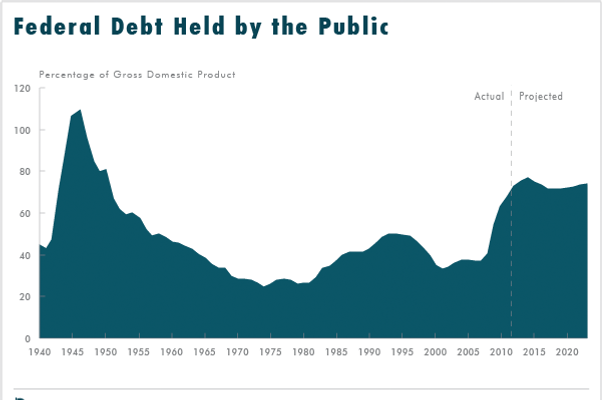

- The long-term deficit is a looming catastrophe of the highest magnitude;

- C-CPI would help avert that catastrophe;

- Obama has made a terrible mistake by pulling back his offer to adopt C-CPI;

- Republicans cannot offer any concessions at all in return for this policy change.

Here, for instance, is John Boehner’s spokesman, Brendan Buck:

“This reaffirms what has become all too apparent: the president has no interest in doing anything, even modest, to address our looming debt crisis. The one and only idea the president has to offer is even more job-destroying tax hikes, and that non-starter won’t do anything to save the entitlement programs that are critical to so many Americans.”

Buck’s first sentence implies that C-CPI would help avert the “debt crisis.” His second sentence asserts that tax hikes are Obama’s “one and only idea” to avert it. But Obama has another idea, C-CPI, which is the “this” alluded to in Buck’s first sentence.

The same incoherence runs through the anguished wails of conservatives, now lamenting the absence of the concession Obama very clearly states he is still willing to make. “Instead of building on the discussions that he has had with Republicans in recent years in which he has at least contemplated a form of entitlement reform,” complains Commentary’s Jonathan Tobin, Obama “refuses to contemplate any fix for the crisis that threatens to ultimately bankrupt the government.”

“Crisis” and “bankrupt” sound pretty terrible! National Review’s Kevin Williamson is even more hysterical:

Playing politics with the reform of Social Security is like watching a tsunami rolling toward our shores and insisting that someone bring you a cappuccino before you sound the alarm — and then sending the cappuccino back for having the wrong proportion of foam to milk.

It’s a tsunami! How dare Obama bargain in the face of this crisis! But he proceeds to endorse the Congressional Republican line of refusing to make even token concessions in return. “John Boehner’s spokesman is exactly right,” argues Williamson. The crisis is civilizational in its scope, C-CPI would meaningfully alleviate it, but Republicans are correct to refuse to offer anything at all – say, scaling back the mortgage interest deduction – to prevent this catastrophe.

I understand this line as an exercise in political spin. Republicans can’t pass any plausible reform through the asylum that is the House of Representatives, so their best move is to lay the blame for any dysfunction on the president. What I genuinely don’t grasp is the calculation from the long-term perspective of the conservative movement.

While I don’t come close to sharing their bug-eyed fear about the scope of the long-term deficit, I do agree that at some point, a fiscal correction will probably be needed. Now here is an important political-economic reality undergirding this long game. It’s politically feasible to cut future retirement benefits, but it’s not feasible to cut current retirement benefits (as even Republican hard-liners agree.) The longer any such correction is postponed, the longer current benefits are locked in. Every year a deal is delayed, the harder it gets to cut spending, and thus the easier it gets to raise taxes. Bolstering this reality is a simple political dynamic: cutting retirement benefits is wildly unpopular. If forced to choose, people would overwhelmingly prefer to raise taxes.

Now, could Republicans conceivably impose a cuts-only fiscal correction, if they obtain unified control of government? That seems highly improbable. Even assuming they do win unified control of government, the collapse of the Bush administration’s plan to privatize Social Security in 2005 illustrates the difficulty of imposing entitlement cuts even under all-Republican government. And even should Republicans manage to pass large cuts to Social Security and Medicare, with no revenue increase on the affluent, Democrats would run against them and reverse those cuts when given the chance.

The really puzzling thing is that conservatives appear to understand this perfectly well. I’ve heard conservative budget wonks explain this unfavorable dynamic to me. Williamson’s column predicts “a gigantic tax increase on your children.” If that’s the alternative to a budget deal, isn’t a small tax increase now perhaps a worthwhile price to pay?

The deficit scolds like to form easy parallels between liberals and conservatives who reject fiscal bargains. But the liberals at least have an argument that the deficit crisis is overblown, and therefore that compromise is unnecessary. Their political strategy follows from their analysis of the budgetary facts. Conservatives simultaneously argue that the looming debt crisis is an awesome, urgent, civilizational catastrophe, that the eventual resolution is likely to be both painful and ideologically unfavorable, and that the Republican Party has no need to compromise on it at all. If conservatives are playing the long game, they are playing it very badly.