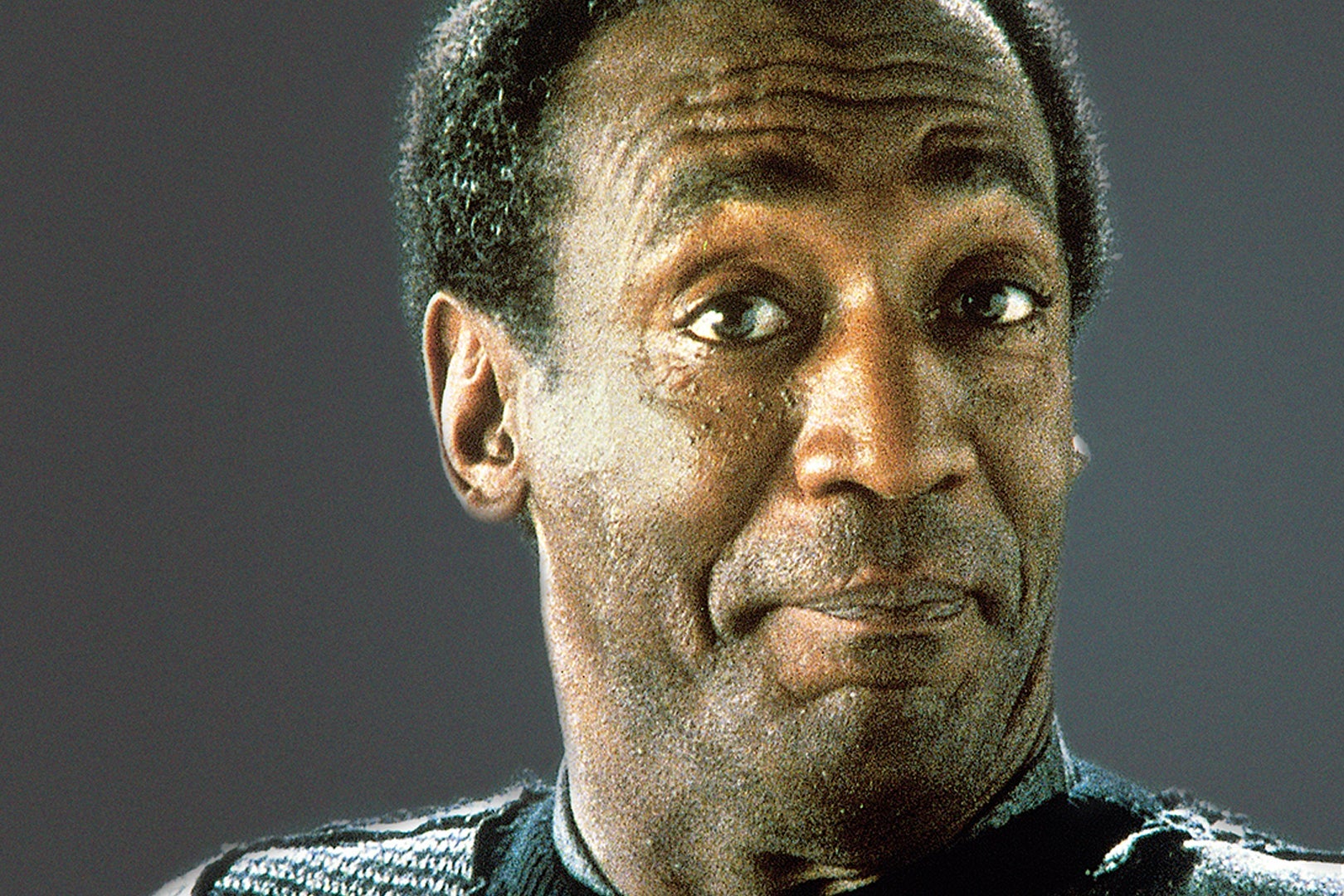

W. Kamau Bell may be a stand-up comedian by day, but he’s also one of our most pointed cultural commentators. His CNN show, United Shades of America, is a documentary-style look at communities across the nation, infusing his slightly cynical, no-holds barred perspective with an unvarnished look at Americans most of us look past.* His Showtime docuseries, We Need to Talk About Cosby—which aired its fourth and final episode tonight—narrows the scope even more tightly. Instead of understanding the unique lives of many people, Bell looks at the life of one disgraced man, and how his crimes affected the lives of others.

When Bell was working on the show, Bill Cosby was in jail for assaulting Andrea Constand, one of many women who have accused him of sexually abusing them, a list that spans over the course of decades. By June 2021, however, the comedian, actor, author, and educator’s conviction was overturned because of prosecutorial misconduct. The prosecution is currently fighting to appeal this decision, but where we stand is that We Need to Talk About Cosby is airing at time when what seemed to be a win for sexual assault victims has been taken away from them. This complicated context makes the series feel even more pressing and necessary than it may have while Cosby was sitting in jail.

Slate spoke with Bell about the lessons he hopes we take away from this series, the parts of Cosby’s career that he could have dug more deeply into, and why we really need to talk about Cosby right now, as he once again roams free. This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Allegra Frank: Unlike similar documentaries about controversial men—Surviving R. Kelly and HBO’s Woody Allen and Michael Jackson series, for example—We Need to Talk About Cosby aired after Bill Cosby was charged for many of his crimes, went to trial, and was sentenced. In comparison, these other shows spotlight criminal actions from popular figures that haven’t been publicly tried yet. Considering this context, what do we still need to talk about?

Kamau Bell: There’s a line in the narration where I say, “How do we reckon with all the good that he did and then reckon with the crimes that I and many others believe that he did?” You boil it down to art versus artist, but nobody is a bigger sort of challenge to that question than Bill Cosby, because it wasn’t about like, “Oh, he was just a funny comedian.” He actually became an example for good in the world, and specifically for the Black community. [He was] the kind of person you should be, who does good work, does good in your community, helps others, hires from your community, encourages people to get educated, then makes it easier through donations for people to get educated. He was a North Star for Black people. But then you find out about these 60-plus women who’ve come forward. I understand people go, “Well, I’m just throwing away all the good stuff.” And then there’s people that say, “Well, I’m not going to believe the bad stuff.” … I understand struggling to believe it, but I don’t have a harder time saying I don’t believe it at all.

[The purpose of the show for me is like,] if I were to invite a bunch of smart, funny people who I’d worked with, people who I sort of knew, people I admired to my house, and we had a dinner party, and at the end of dinner, somebody was like, “Can we talk about Bill Cosby,” this is the conversation that would be had. It would be all over the place. It would not just be focused on one area. … You would sort of go, “Let everybody have their place to talk.”

[A big inspiration was] O.J.: Made in America, which is like, how do you talk about OJ Simpson? Well, you talk about O.J. Simpson by talking about the America that he grew up and lived in. That was such a revelation. I always think about the part at the beginning where it’s clear we’re going to talk about the murders of Ron Goldman and Nicole Simpson. But it’s also clear that we’re going to talk about how good he was at football. Within a few minutes of [Made in America], you’re like, “Man, he was good at football.” Then your brain’s like, “What are you talking about? Why would you say that? I don’t know he was good at football, but he also did these things.” And director Ezra Edelman’s inviting you to take the journey with him and go, “We’re going to get to all of it. Don’t worry.”

With [We Need to Talk About Cosby], I thought, we’re going to get to all of it, don’t worry. But you have to let the audience know that even if it feels like we’re skewing one way, we’re going to get back to the other thing. … I really took that approach of, the only way to talk about any of it is to talk about all of it. And also, at some point in the middle of making it, it became clear Bill Cosby wanted us to learn from him. This is another opportunity for us to learn from him.

The show starts with Cosby graduating from Temple, starting to do stand-up, starring on I Spy—going through his career chronologically. But each episode also makes sure to intercut that chronological story with interviews with the women who have him accused him of sexual assault or other, more contemporary aspects of his life and story. How did you decide to balance all of those storylines?

This is where as a director, I could be like, “Well, I really worked hard on this. And it was really all my idea.” [But] you have to have editors who can help you, because they know how to work with tone. So there would be times where things would be sent to me, and I’d be like, “Oh, that’s it. I wouldn’t have known how to tell you to do that. But you understand.” I’m thinking about Jen Brooks, who edited across the whole series and was with the project from the beginning. But we had many editors because of COVID—you have to shut down, and you can’t get that editor back. … There were editors who were particularly skilled at the fun montage sort of things. and there were editors who were particularly skilled at the survivor interviews, and then it becomes, how do you fit these things together?

That’s where eventually we brought in my narration to help tie these things together. Sometimes you do want people to take a left turn that they weren’t expecting, and then sometimes you want to be able to let me walk you through why we’re going here. I think the first episode was the biggest challenge [to balance], because you do want to do a lot of scene-setting to go, “This is who this guy was and what his life and this is who this guy was and how America met him and how he transformed America through his presence in a lot of ways.” But you don’t want people to be like, “Wait, did I get tricked into watching just some sort of Bill Cosby praise piece?” So you have to figure out ways to, even in that first episode, as Kierna Mayo [former editor-in-chief of Ebony] says it, put some breadcrumbs out.

Another recurring element of the show is where you’ll zero in on a joke, a comedy routine, or a scene and show people interviewed reacting to it with the benefit of hindsight. You had a few interview subjects react to the fact that Cliff Huxtable on The Cosby Show was an OB-GYN with his office in the basement, or that Cosby released an album about how to teach kids about drugs. Why did you think having your subjects reflect on these elements in hindsight was necessary to include?

I was born in the early seventies, so I feel like I was basically born into the heart of Bill Cosby’s career. Fat Albert was on Saturdays. [Bill Cosby] was on Picture Pages. By the time The Cosby Show comes around, I was already a Bill Cosby stan. But I’m also aware that if you’re under the age of 35, all you know him from is Cosby Show reruns on Nick at Nite or something. You don’t really understand why people are making such a big deal about this guy. And then my mom, who’s the same exact age as Bill Cosby, was like, “Oh, you don’t understand about I Spy and how big that was.”

The more you start looking at his career, things jump out. I had no idea he recorded an album about drugs called Bill Cosby Talks to Kids About Drugs until Kliph Nesteroff, the comedy historian who’s in [We Need to Talk], talks about the album. And then [I went to] find it and it’s him telling kids about uppers and downers and acting out what a downer does to you and how it makes you slow down. The frame around it is like, he doesn’t want kids to be on drugs, but it’s also done in a way that feels not well-researched, and it just feels like he’s not taking it that seriously.

He won a Grammy for it. You should have been able to look at this at the time and go, “This is not a Grammy-winning album,” but he won a Grammy for it. Once you’re in the industry and the industry starts to celebrate you as being the best Black in America, you get things that other people wouldn’t get. I think the idea [of showing reactions to these things is] that, once you look back, these things leap out at you.

Before there was an idea there would be a documentary series, I was somebody who was like, “I can’t believe he decided to be an OB-GYN with an office in his basement, on The Cosby Show.” And every time I brought that up to somebody, they’d be like, “What?” They thought I was lying, like how I thought Kliph was lying about the album. And then when they remember it, you could just see people’s faces just drop. Of all the professions to pick, of all the specialties of doctor to pick, he was an OB-GYN with an office in his house, which doesn’t even make sense. You could have put the office down the street—it’s television. You could have put the office on Mars. But the choice to put it in the basement of his house was just so galling, and I think there’s a lot of things like that, when you look through his career, look different once you look back. Ultimately the invitation is [to] look around us right now. I’m not going to indict any comic for any joke they do, but I am going to start to look at it if you do a lot of jokes about this. Maybe it’s just jokes, but is there more here?

The majority of the people included in the show were people who come down very strongly against Cosby, either because they were victimized or because they were otherwise negatively affected by him. Which is why I was struck by how you had people read between the lines of Cosby’s jokes about drugs or women and regard them as intentionally placed. Were there people that you wanted to talk to or weren’t able to, who were more interested in defending Cosby’s actions? Or did you consciously choose not to include anyone with that perspective?

When I did The Daily Show, Trevor Noah talked about why he said no [to appearing in the doc], and I appreciated him saying it. And it was because … Bill Cosby was not a part of his universe when he grew up so he doesn’t have the same relationship. But I would say that if I had a stack of people who said “no” and a stack of people who said “yes,” the stack of nos would be way bigger than the yeses.

To sort of drill down on the Cosby defenders, of course I thought about that stuff. And there’s also plenty of clips I could have put in to show people like that. But to me, this is ultimately about a productive conversation and the doc fully owns the fact that I, the director of this doc and executive producer of the doc, believe the survivors.

I don’t know how to include [defenders] in a way that doesn’t feel like I’m somehow calling the stories into account. I get the feeling of not wanting to believe it, and I think we’re addressing that. But on some level it’s like, as somebody who has promoted COVID vaccines a lot and has done PSAs to promote people to get vaccinated, I don’t want to include the arguments of people who say the vaccine is going to make you magnetic. We’re not going to have a productive conversation if we do that. This is similar to that.

I’m fine if you have struggles believing [the allegations]. And we include people who struggled, like … Joseph C. Phillips [who played Martin on The Cosby Show], who thinks the barbecue sauce clip from The Cosby Show is something that we’re making too big a deal out of. But he also said he didn’t believe it until he asked the woman in his life who he knew was close with Bill, and then she started crying. Showing people who didn’t want to believe until evidence was presented in a way that they couldn’t deny is way more interesting than showing people who are like, “I don’t believe full stop and here’s ways in which I’m going to gaslight this conversation.”

I imagine it would be difficult to figure out how to include those who actively defend him and even tacitly or unintentionally refute survivor’s stories without appearing as though you are platforming them.

I’m a guy who talked to the Klan, and I wouldn’t do that again at this point in American history, I’m not saying I regret doing it then, but I’m saying at this point in American history, we have to stop pretending that just because somebody has an alternative viewpoint, that it’s a legitimate side.

There are people who were allowed to go into spaces that are supposed to be about intelligent dialogue and say, “What’s the big deal with January 6th?” And you’re like, “Well, the big deal is that if we keep saying, ‘What’s the big deal’, we’re not going to have a country anymore.” This show is the part of that. People can have their own viewpoints about this, but I want to have a productive conversation and also a conversation that overall is about how to create more safety and more support and more justice for, specifically in this case, women who survive sexual assault and rape. I think that whether or not you believe Bill Cosby did it, you should want to be in on that conversation. And if you don’t want to be, then I don’t think we really have much to talk about.

That’s something I struggle with as a journalist too—when you want to report on something objectively, do you want to include the viewpoints that you, as a human being, know are bunk? The vaccine is a great example.

This is where I get to go, “Yay. I’m not a journalist.” But having said that, I want journalism to vet the things I’m saying, and I want to be clear when this is a fact, or this is my opinion. I’m not trying to hide away from facts. I love facts, because often they help me prove my opinions and they help me bring nuance to my opinions. But I do think that the one thing that I’ve enjoyed about my weird career is that I do work at a news network [CNN], but full stop, that news network does not expect me to be a journalist. They expect me to use the tools of journalism to prove my case. I think the same [is true] with Showtime. Vinnie Malholtra, who’s the executive at Showtime in charge of this, said, “This is an op-ed from you. This is your op-ed.” This was not, how do we solve the case? I’m accepting that the case has been solved. How do we deal with the consequences?

It sounds like not having that true crime-like element to your Cosby portrait gave you additional latitude to explore different angles of this story.

It gave me the right to be who I am and not trying to be somebody else. It gave me the right to be the kind of creator that I want to be. It gave me the right to be a standup comedian and make it funny when I wanted to. It gave me the right to understand that I don’t want this to be intense for four straight hours. I mean, it is intense, but I want to be able to include a survivor saying “I got fucked in more ways than one,” which is like whew! and also powerful, that she’s not taken over by this story. She’s in the driver’s seat of this story.

You can be an 85-year-old white woman and have opinions about Bill Cosby because he was a part of your life, and you can be a 49-year-old comedian like me and have a perspective on this. And I want us to all come here and speak the way we speak in this thing, without feeling like we have to shave off our rough edges for the purposes of sounding like we’re all on the same page.

How did your own feelings about Cosby change over the course of making the doc?

It deepened on all sides. I think there’s a way in which those of us who even support the survivors can reduce their experiences to, and this is the coarse way of putting it, 60 one-night stands that went wrong. Then you really find out how much Cosby was in a relationship with some of these women and how he flew them around the country and how he led them to believe that he was going to do something for their career, and how some of his experiences with these women went on over the course of years. He would disappear from their lives and pop back up. All this is out there. You can find it. He was really working as hard at this as he was at his career in many ways. And then you look at his career and you go, wait a minute. The stunt industry in Hollywood might still not be in the right place if Bill Cosby, on the set of his very first TV show, hadn’t said, “Get me a black stuntman, or I don’t work.” That’s empirically good.

Lili Bernard, who’s one of the survivors, is very clear about what he did and is not in any way afraid to speak up about it. Also, her whole face brightens up when she talks about how many black people worked behind the scenes on The Cosby Show. You can see her admiration in that moment for what he did there. There are people who trace their careers in Hollywood, black people, to them getting hired on The Cosby Show in a way they wouldn’t have gotten hired on any other sitcom.

I think that we need to talk about Cosby, because you can’t take all of this for granted, especially if you want to learn from it, which I want to. I’m always trying to learn from these things. I mean, right now we’re in the middle of this whole thing in school districts around the country, pushing out critical race theory. Why would you not want an accurate teaching of history in this country unless you’re trying to protect certain interests? And those interests generally are the interests of racist white men. Why wouldn’t you want to tell the whole story?

Was there anything that you wish you had more time to dive into or include?

So many things. I struggled with how little we talked about [A Different World], and I think we tried, because it was such an influential thing. Four hours sounds like all the time in the world, but [the third episode] specifically covers like 30 years—we could have done an episode just about The Cosby Show and then an episode about everything after The Cosby Show up until Hannibal Buress. But we didn’t have that time. It is what it is.

We didn’t get to Little Bill. One of the Little Bill books is called The Big Lie. There’s more we could have done to talk about rape culture. … I saw somebody on Twitter say [their] only criticism is that the show didn’t bring up grooming when it talked about all this. And I was like, “That’s a legit criticism.”

Four hours sounded like a lot to me until I realized, wait, Episode 3 is covering 30 years? Episode 1 covers, I don’t know, six or seven years. Episode 1 is an hour and it covers from 1962 to 1969, I think. Episode 3 covers 1984 until 2014. It’s definitely a situation where we bit off more than we can chew, but I hope people appreciate the effort we made to chew it all up. Which is a really bad analogy, but that’s where we’re at right now. Sorry.

Correction, Feb. 21, 2022: This piece originally misstated the title of W. Kamau Bell’s show. It is United Shades of America, not United States of America.