The Photographer’s Eye

John Szarkowski Museum of Modern Art, New York 1966 156 pages, 172 gravure illustrations, $5.95

The Photographer’s Eye, full of stimulating images, is the most recent visual and verbal definition of pure, natural, or straight photography in a series that includes Beaumont Newhall’s first edition of the History of Photography, 1937, and this reviewer’s exhibition, “Lyrical & Accurate,” a resumé of which was published in Image, October, 1956.

Regardless of the decade, for anyone to look at the whole corpus of photography, from top to bottom, is a fascinating experience. This experience can be somewhat objective. Trying, however, to find fundamental words or basic concepts by which this whole body of photography can be examined is always a subjective affair. Each of us hopes that our names for concepts will become a part of the vocabulary of criticism and that our selection of illustrations will become part of the visual vocabulary of image making. Photography, like the phenomenon of life itself presents different facets constantly. Consequently if our word structures crumble, the image material itself does not. The photographs remain in spite of intellectual structuring.

John Szarkowski structured his book into five categories: and gave them titles as direct and simple (antiintellectual) as most of the photographs themselves: The

Thing Itself, The Detail, The Frame, Time, and Vantage Point. The collection of pictures themselves, present a sixth classification he did not name. In the “Lyrical & Accurate” exhibition, at George Eastman House some years ago, I called the quality ‘the innocent eye.’ Szarkowski combed the major society and private historical collections of photographs in this country. The result is too innocent to be an accurate reflection of the whole body of photography. (By comparison Newhall’s History leans towards the aristocratic, while “Lyrical & Accurate” was over-poetic.) At the level of the untrained photographer who has no art background to either burden him or help him innocence of eye is often unbelievably stupid. Szarkowsky omitted the stupid. Innocence of eye by Edward Weston is an earned, that is, a coming full circle, and hence no longer naive. Eugène Atget had this kind of innocence, so does Henri Cartier-Bresson.

To help my own understanding of the definitions of the various sections I have paraphrased them. The Thing Itself seems to mean a direct confrontation with the object in front of the camera as an isolated event. Vantage Point refers to the photographer’s confrontation with the relationships of togetherness and backgrounds that appear in front of the camera. These two concepts are uncontestably basic to the medium, and the order of presentation is in keeping with the practice of beginning photographers. The beginning photographer rarely sees relationships. It is the single object that holds his attention, the rest escapes him, while photographing, and when looking at the print later the rest still escapes him! Relationships, Vantage Point come later, much later.

The illustrations for The Thing Itself are arranged in such a way that the concept is muddied rather than clarified. For example, the opening photograph, Bedroom Interior (by an unknown photographer, circa 1910) is actually a photograph of relationships not a photograph of a thing. His text explains that the thing means subject as well as object which is a confusion. The first three photographs suggest that The Thing Itself is to be a bedroom. Obviously this is not what was intended, yet this is where the reader is started on a journey into The Photographer’s Eye. Not one photograph in the entire section confronts the viewer of the image with a single object which is implied in the word Thing. The closest to this requirement is Wright Morris’ photograph of a Model T Ford, 1947. Yet this photograph is really a detail, a part standing for the whole. In my own terminology it could illustrate the “anthropomorphic” photograph.

The book, as was the earlier exhibition, is somewhat didactic in nature, and since that is the intention, I would like to see the concepts powerfully and convincingly illustrated. If the first half dozen photographs visually drove home the point of each section, even with a sledge hammer, then the rest of the photographs could be sequenced so as to extend each of the five concepts in all their potential directions.

The Vantage Point includes photographs made with the camera pointing down, pointing up, sitting on the floor, perched on the ridge pole, wide angle lenses and so on, all of which are essential to the idea of vantage point. One of the photographs by Robert Frank illustrates unmistakably how vantage point can be used to make a biting, sarcastic statement.

The text for The Detail section seems to boil down to the observation that once the photographer left his studio he could not “stage-manage the battle” intuitively, and so he sought and found significant detail. His photographs were incapable of narrative and so he turned to symbol. This introduction leads the reader to a very limited comprehension of photographic symbolism, namely the photograph of the part stands for the whole event. Photographic symbolism, however, leads in still other directions and distances. The metaphor or the symbol can stand for an event, it can stand for a place, to some extent it can even stand for the whole of a person, as Szarkowski indicates. Beyond that the detail can stand for inner psychological states and still beyond, spiritual change. The five photographs of hands by five photographers grouped together could have opened the section effectively because they form an easy entry into the idea of the detail standing for the whole. Ovious, yes. But lucid. They would have helped convince us of his contention that the single photograph can not narrate. He points out that since the photograph can not tell the “hero from the villain” that the photographer is forced over and over again to use the detail. There is no little truth in Szarkowski’s contention so far as the single photograph is concerned. He did not mention, however, that several photographers have sought other solutions to the problem of photographic narration. I, for one, use the detail and the single photograph to build up an emotional story that in turn builds up a feeling state. The details become like words in a sentence.

The section called The Frame is a frank recognition and a pointing out of the effect of format upon picture shape and content. The text for The Frame contains these interesting observations. “To quote out of context is the essence of the photographer’s craft.” And later, “While the draftsman starts in the middle of the sheet, the photographer starts from the frame.” It might be well worth repeating that photographers have to learn to start with the frame. The figure in the center of the view finder is as much as beginners ever see.

The section on Time is the most lucid in the entire book. It includes what we would expect, long exposures of standing still objects, to the opposite extreme, objects in motion so fast that until the camera came along the forms had been invisible. He uses Time also to include those brief moments when the flux of relationships falls into a specific fix which, from our long relationship to art, we are glad to call “a picture.” Part of the text from this section reads, “Photographs stand in a special relation to time, for they describe only the present.” At a naive level this is true. His illustrations verify this particular truth. Beyond this the “present” of a photograph is analogous to the detail standing for the whole: that is, the “present” in a photograph can also relate to psychological time which is never a point but always an expanding and contracting and pulsating experience.

A last quotation from the general introduction. “This book is an investigation of what photographs look like, and of why they look that way. It is concerned with photographic style and with photographic tradition: with the sense of possibilities that a photographer today takes to his work.” I don’t believe that the “sense of possibilities that a photographer today takes to his work” is nearly as limited as The Photographer’s Eye indicates. The corpus of photography includes sophisticated photographers mature and cunning of eye. The transformations photography performs on things is still another constellation of attitudes that mature photographers bring to the medium.

Such books as The Photographer’s Eye are always useful and generally necessary to help photographers see the body of photography whole. They are needed every decade or so. Consequently, sooner or later another exhibition and another book will appear in a new attempt to define this devilishly elusive totality called photography. Good luck in advance.

Minor White

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

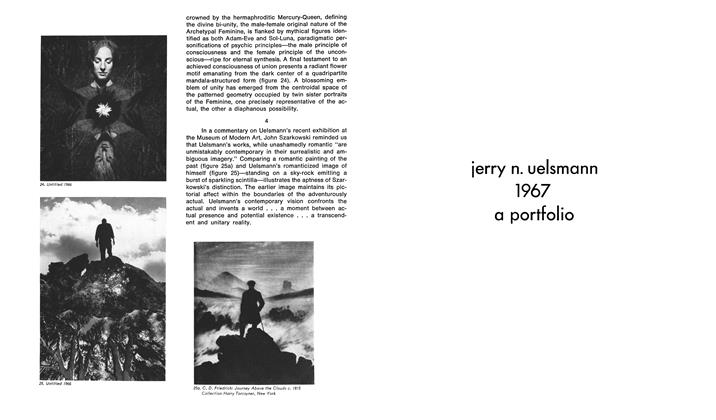

Uelsmann’s Unitary Reality

Fall 1967 By Wiliam E. Parker -

Leslie Krims

Fall 1967 By Peter C. Bunnell -

A Meeting Of The Portland Interim Workshop

Fall 1967 -

Jerry N. Uelsmann: 1967, A Portfolio

Fall 1967 -

Comment And Review

Comment And ReviewPhotography And The Mass Media

Fall 1967 By John Szarkowski -

Excerpts From The Critique

Fall 1967

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Minor White

-

Concerning Significant Books

Concerning Significant Books5 Reviews Of "Under The Sun."

Winter 1960 By Barbara Morgan, Van Doren Coke, Minor White, 3 more ... -

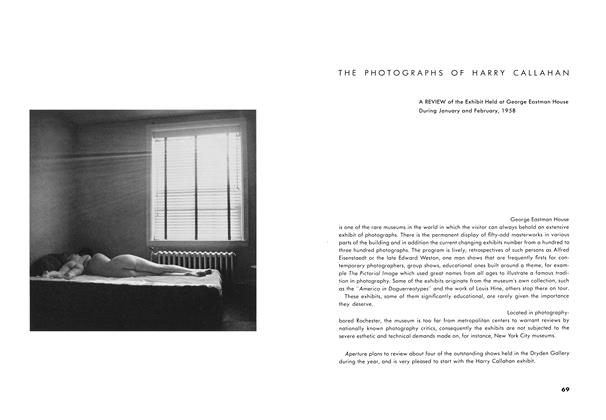

The Photographs Of Harry Callahan

Summer 1958 By Minor White -

Editorial

Summer 1961 By Minor White -

Exhibition Review

Exhibition ReviewThe Photographer And The American Landscape

Summer 1964 By Minor White -

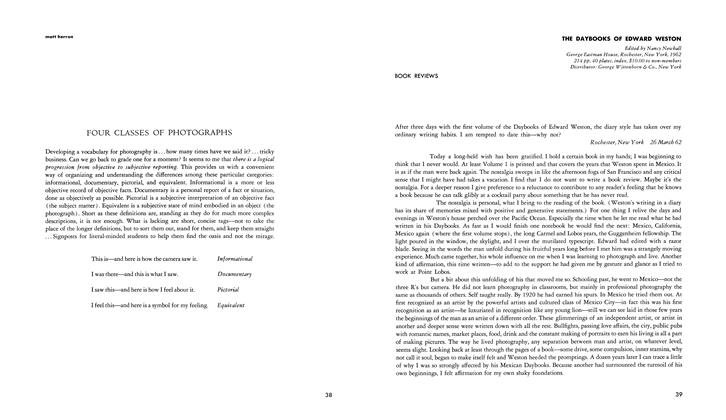

Book Reviews

Book ReviewsThe Daybooks Of Edward Weston

Spring 1962 By Minor White, John Upton -

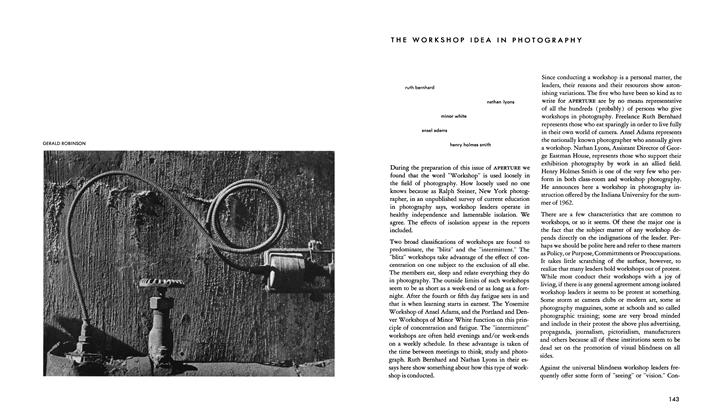

The Workshop Idea In Photography

Winter 1961 By Ruth Bernhard, Minor White, Ansel Adams, 2 more ...